Chapter 1:

Prologue - The White Raven

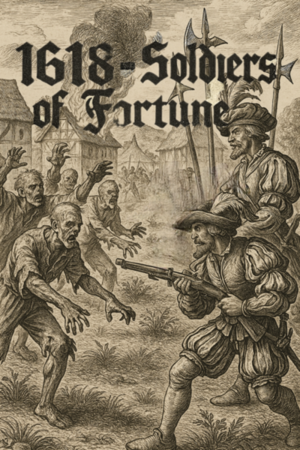

1618 - Soldiers of Fortune

The first light of dawn crept through the narrow garret window and roused me from a heavy, muddled sleep.

My throat felt parched, my head dull; for last night’s wine had been stronger than was wise.

I rose and opened the window.

A cool morning breeze drifted in, easing the stale heat of the night.

Across the fields the estate lay still in silence, until a flicker of white caught my eye.

Upon the great oak before the yard perched a bird unlike any I had ever seen, its plumage white as bleached linen, its beak faintly rose-hued.

For a moment it seemed to regard me, then it vanished among the leaves.

But before I could ponder it further, a soft voice made me start.

“Oh… beg my pardon, sir…”

Anna stood behind me, though I had not heard her enter.

A slender maid of fifteen or sixteen, with long brown hair tucked beneath her cap.

“I hope I do not disturb you, sir. You did not answer, and I wondered… will you not take your breakfast?”

I glanced again at the oak, but only the faint stirring of branches remained.

Whether the bird was bad omen or illusion, I could not tell.

“Is aught amiss?” Anna asked quietly.

“It is nothing,” I said. “I shall come down presently.”

She nodded and withdrew.

I dressed quickly, breeches, boots, doublet; nothing more than what duty required, and descended to the dining room.

The table stood yet set.

Bacon lay upon a pewter platter; rye bread, a bowl of grapes, the last of the honey, and a jug of watered wine completed the fare.

“So much remaining? That is not in Father’s manner,” I remarked. ”Where is he?”

“Master departed more than an hour past,” Anna replied. “He said he must ride to Kernstett and would not return for several days.”

I nodded as though the news were new to me, though I had counted upon this very journey.

With Father from home, I could stir about as I pleased; and the meeting I intended would raise no question.

I ate in silence and the watered wine eased what remained of my headache.

“Where is Bertram?” I asked.

“He went to fetch water for the horses, sir. He ought to have returned.”

“Bid him ready the mare. I must ride to town.”

When I had finished, I took my cloak and broad-brimmed hat, buckled on rapier and pistol, and stepped outside.

At the stables the mare, Venus, already stood saddled.

Bertram, dirt-smudged as ever, kept his distance; the boy understood horses better than most, but I had no time for his temper.

I mounted and set off at once.

***

When I reached the city gate of Stratweiler, the sounds and smells of the market already pressed in around me.

Meat and fish, fresh bread, hides, iron and steel; the cries of merchants, the murmur of townsfolk going about their business.

At some stalls, spices from the East and tobacco from the New World were offered to those with coin enough to pay.

I made my way toward the small chapel near the servants’ market.

Within, the chapel was already crowded.

I took my place at the rear, wishing to draw no eye upon me from any who might know me.

The Latin of the Mass washed over me; I understood little and cared less, my thoughts already elsewhere.

When the Agnus Dei had finished, a man in the black-and-white habit of the Dominicans stepped forth.

“Beloved in Christ,” the priest said, “we welcome Father Gerlach, personal emissary of His Grace Ferdinand of Bavaria...”

“...sent hither,” the Dominican cut in, his voice firm though not loud, “to warn and to protect.”

He took the pulpit and preached of heresy creeping into honest houses, of false doctrine, of witchcraft, and hidden sins.

Murmurs ran through the nave; some crossed themselves, others nodded with grim faces.

I sat motionless, unease tightening in my chest.

Ferdinand of Bavaria was feared for his witch-hunts.

Many had died under his ordinances elsewhere in the Empire, and now his agents had come to Stratweiler.

When the Mass was ended, I remained where I was until the last of the folk had filed out.

Only then did I leave the chapel and make my way toward the lower town, near the Jewish quarter.

For my appointment waited.

***

The tavern lay half in shadow, though outside the sun had climbed toward noon.

Smoke from damp wood curled along the rafters; the scent of boiled cabbage and old ale clung to the air.

Harrer sat in the rear corner, back to the wall, where he could see both door and window.

A deliberate position.

He did not rise when I approached.

His eyes, a cold, unyielding green, lifted to me briefly and then dropped again to the silver watch on the table before him.

He clicked it open, closed it, tapped it once with his thumb.

“You’re late,” he said.

I bowed my head and sat opposite him.

A tremor ran along my fingers before I hid them beneath the table.

“You ask after a lieutenant’s rank,” Harrer said. “A curious ambition in one who cannot keep an appointment.”

“I beg your pardon, sir…”

He raised a hand.

“Have you brought what I bade you bring?”

I set rapier and pistol before him.

He inspected neither; he merely let his gaze rest upon them, as though weighing not the weapons, but the man who carried them.

“The breastplate shall be ready on the morrow,” I said.

“Good,” he murmured. “Yet armour is not the matter.”

My throat tightened as Harrer steepled his fingers.

“I may secure you a place in the regiment,” Harrer said quietly. “Perhaps as a corporal. But a lieutenant’s rank, without service to your name, such a thing calls for… persuasion.”

The expected word hung in the air.

I placed the first pouch of coins upon the table.

Harrer did not touch it.

His gaze flicked to the doorway behind me, scanning the room for watchers.

“And the quartermaster,” he said, as though speaking of the weather. “And the supply master. They, too, expect persuasion.”

I laid down the second pouch.

Then the third.

A whisper of panic stirred in me, not at losing the money, but at whether even this would suffice.

Finally he reached out and swept the pouches toward him with one scarred hand.

His fingers bore calluses thick as hide; powder burns mottled the knuckles.

“And now,” he said softly, “my payment.”

I drew forth the final pouch, the one I had sworn not to touch save in direst need.

Harrer watched my face as I set down the last of my savings.

He took it with a short, satisfied nod.

“Good. You shall hold the rank of lieutenant,” Harrer said at last.

A flicker of triumph rose in me, immediately chilled by the look in his eyes.

“Do not mistake me,” he said. “A bought rank is but a borrowed blade. The men shall expect you to prove yourself. Fail them, and they shall not only mock you.” His gaze hardened. “They shall let you die.”

I steadied my breath.

“I shall not fail.”

“That remains to be seen.”

Harrer leaned in, lowering his voice

“We march soon. There is talk that our next campaign shall begin ere summer’s end.”

A faint, humourless smile crossed his lips.

“You desired war, did you not?”

“I desire a life of mine own,” I said, and regretted the words the instant they left me.

Harrer’s expression shifted, whether to pity or to mockery, I could not tell.

He rose then, turning his head but once ere he left.

“Report to the provost the day after tomorrow,” he said. “And keep out of sight till then.”

Then he was gone.

For a moment a spark of excitement stirred in me, but it was met by a colder sense of gravity.

Still, the choice was made.

I would not spend my life tending Father’s horses.

The world lay open now, and I had set my foot upon its road.

War was no longer a tale brought by passing merchants.

It had already begun.

Please sign in to leave a comment.