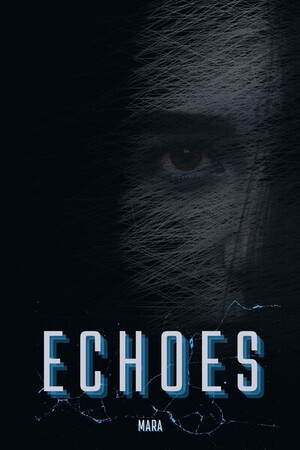

Chapter 3:

Another Brick in the Wall

The Fourth Month Of The Spring

Early March. That time of year when snow still clings stubbornly to the ground, but the wind already carries the damp breath of spring.

That very moment when Colonel Thaw rallies all his forces for a sudden strike against General Frost. A fierce battle will soon begin, followed by a guerrilla war. The General will resist, launch counterattacks, but sooner or later he will fall — only to return triumphantly somewhere around December.

It happened every year.

So, March.

I still sat at the front desk and had more or less gotten used to the occasional teacher's shout flying right past my ear to the back of the class. We were in literature class, receiving the essays we’d written a few days ago — a character analysis of a literary figure. The distribution proceeded steadily, grades announced in a monotone, occasionally with a comment or two. I waited patiently for my name, trying not to drift off — it was still first period, after all.

Finally, my name was called. But with a special kind of emphasis, as if the teacher was hurling out built-up irritation through the very syllables of my surname. I reached out for the paper without getting up, but she pointed sternly to the empty space beside her, demanding I come forward.

Mildly puzzled, I walked around the teacher's desk and stood next to her.

Our literature teacher was a rather elderly woman. Widely regarded as the best in her field — and not without reason. First of all, she was a well-known literary critic, who had torpedoed the careers of dozens of aspiring writers and didn’t hesitate to eviscerate even the acclaimed masters of the pen. Secondly, her lengthy tenure in the Committee for Print Oversight had allowed her to crush — quite literally this time — no fewer poets and writers who were too direct in expressing certain viewpoints on paper.

So when a person like that says your name in that tone, waving your handwritten paper in the air — something inside you clenches on its own.

Now she was glaring at me from behind her small, rectangular glasses.

— What is this? — she extended my essay toward me.

— It’s... an essay.

— I’m aware. Did you even read what you wrote? — she was practically hissing in my face.

— Y-yes. I reread it. Twice — I swallowed nervously, staring at her neatly styled black hair streaked with gray.

— You ought to reread your essays better. You’ve had questionable work before. But this — she snapped the paper sharply — this crosses the line! What is this “I dare to question,” “not as negative as he may seem”? Huh?! If a character is labeled as negative — then he is and will remain negative, from start to finish. The author suggests — the Committee defines. You do know that, don’t you?

Yes. I knew that.

That very innovation, for instance, had killed the detective genre. What kind of intrigue can there be when every book opens with two charts: one green — for positive characters, and one red — for negative? Even dialogue was color-coded. All for the reader’s benefit. Why should the reader think, after all? Why would the Republic need thinking citizens?

Store shelves were flooded with mass-produced "literature" following a few approved plot templates, with only character names and minor details altered. I’ll never forget how, after reading all the old books we had at home, I went to a bookstore in search of “modern” literature. First came surprise at the marked-up text, then déjà vu after several flashy titles with captivating covers.

Then I silently packed the new books into a bag and dropped them off at the nearest dump.

It felt dangerous to read them.

Old books were no longer published or reprinted — they did not "meet the high standards of literature produced in the Republic." Produced — yes, the mission to turn literature from art into mere entertainment had been accomplished.

And now I stood in the classroom, next to the teacher’s desk, humbly awaiting my fate.

— Just so you know: for this... "piece of work", you’re getting an F. One more attempt at “creative freedom,” “independent thinking” — call it whatever you like — and it won’t stop at a failing grade. The consequences will be such that you’ll regret writing this for a long time. Is that clear?

I nodded grimly and returned to my seat.

— An F? Don’t worry. It’s just another essay.

— Honestly, the grade doesn’t bother me. I’m more concerned about explaining this to my dad.

Beneath the final sentence of my essay was a thick red line, and under it, a bold handwritten note:

"F. The essay entirely contradicts the official character guidelines for the assigned text."

— So, your dad’s going to be mad?

— Yeah.

— Oh. He's one of those, then.

— Exactly — I smirked bitterly.

— Well, my parents used to call both me and my essays “strange.” Though, I must admit, I’ve never gotten such an... eloquent postscript — she shook her head in surprise.

I tore my eyes away from the bold scrawl — a heavy seal over my creation.

— “Strange” doesn’t mean “bad.”

She looked at me, surprised. I met her eyes with focus.

It was like I’d changed my face, and she’d changed her eyes — and for the first time, we were truly looking at each other.

Her left cheek twitched, as if holding back words.

I rolled my shoulder and turned straight again.

A theater of nervous tics. Just don’t let your eyes water. Pretend to yawn. Or actually yawn…

I walked home in a daze.

The essay and that strange look filled my thoughts. The paper — condemned as “contradictory” — would have to be shown to my father, and that would go badly. And the look — the look would now serve as fertile ground for endless overthinking and imagined meanings that may not even exist.

I was so lost in thought I didn’t even notice the unusual chirping of birds for early March, echoing through the kingdom of dirty gray snow.

And I no longer noticed the smell.

Please sign in to leave a comment.