Chapter 7:

LETTER 4

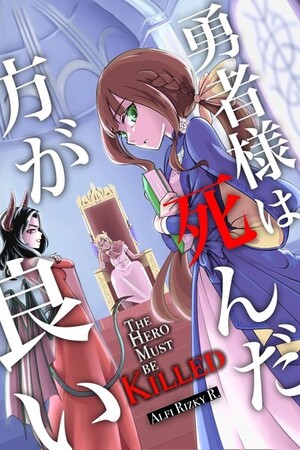

The Hero Must be Killed

Miss March—

My father taught me very early on in life that good and evil both exist, and are both very real, but also that nobody is ever truly good or truly evil. Everyone is born with goodness in them, and most will behave in a manner that is good as long as they are taught properly, but along with that goodness, everyone has in them the capacity for evil. To be good is not nature, Father said, but a struggle.

Being good is hard, he said. Maybe that’s why I haven’t been feeling very good, especially in matters relating to the Kingdom of Admari.

Don't get me wrong—I have no real hatred or such sentiments for that kingdom. If anything, I understood a fair amount too well the kind of pride it brings upon one who stands up for the good of their kingdom. It’s just that the number of times the Kingdom of Admari has been crossing the line of what I thought should be the appropriate treatment of a hero has started being difficult to count, and whatever impacts the Hero, impacts us all—and that includes me.

I love my own kingdom of Lenamontis. I was relegated to helping with frontline defense before my tenth birthday, a mere child asked to risk her life for a grander good, and yet I still love my kingdom. Each time I stand on the walls that set apart my domain from the demons’, each time I look at the trenches my family dug and defended for generations, each time I sling a spell to an incoming enemy or scream my speeches to the soldiers from my little frame, I felt pride. There is no honor in death but one that is earned, Father taught me, and I felt like I had to earn my share. My Father kept warning me that he might pass away while I was still very young. It did not happen, to the Graciousness of the Goddess, but I did prepare for the day it would come to pass, and oh dear, did I prepare very hard for it.

I was ready to die defending my men, my kingdom, my fellow dwellers of the land; I was ready to die for my mother, my brother, my sisters; and for every mother, every brother, and every sister out there. I was ready to die for my father, even if he was not ready for me to die for him. I was ready to put my life on the line. I’ve always lived that way.

Sir Tanaka opened my eyes. I did not look at a grand enough scale, he said. If I were to lay down my life, I lay it down for others—but it shouldn’t matter who, he said. In the end of the day, even with our capacity for evil, we must understand every evil that we do, that we’ve done, that we must do, that we had done, and for each sin we carry, we must be ready to atone in prices untold in terms of gold. In the end, everyone fights the same fight, some simply worse off than others, and others better. Those who fare better aren’t always kind, but the best of them would find it in them to help others who are worse off, regardless of who they might be.

What I did was already good, but I could do even better.

It did not make the slightest sense to me—as anyone on the other side of Constantian walls were just always simply my enemies, so who cares?—but who was I to reject him when he’d traveled the world?

And he was not being a hypocrite about it, either. Miss Scarlet was one such example. Whereas every other demon who came with malice was met with equal hostility, Sir Tanaka would open his arms, even for the enemy.

I’ve long warned him about them. “They are born evil,” I told him when he stayed in my villa. The Dukedom of Constantius was actually among the first of his destinations, as he said he wanted to get a feel of the war proper—his training did not exactly expose him to many demons, except maybe those who hid in our midst. “When they attack, they will attack to kill. You have to kill them back.”

“Hmm,” he said. There was pensiveness in his eyes that I couldn’t decipher at the time. “I wonder.”

He knew something I didn’t. That much I could quickly surmise—although I had no idea at the time that he had already not only fought, but also conversed with the demons. But I felt like I had to at least give him a warning. He was entering unknown territory, facing his first actual demons in his first actual war, and I had to at least equip him for what he’d face.

I still feel like my warning then was warranted. I’ve seen demonic children, and even they seemed very aggressive to each other. I remember seeing demonic children on the battlefield, too. Oh, I killed one, even, when he tried to strike me with a barely-functional Arcane Art.

I remember talking to Miss Scarlet about it, maybe to ease my conscience, but she laughed at my face.

The way demons laugh had this mocking quality to them, but Miss Scarlet felt less demeaning and more … entertained? Her deathly pale skin and deeply dark hair had always made her feel alien to the rest of us—though her horns not so much, since certain beastfolk were also horned—but there’s detachment in the way she treated things, in the way she treated other entities, and that was the impression I got from the way she laughed at me.

Or, well, not at me personally, as I later learned, but at the fact that I tried to talk about feeling guilty regarding demons.

“I couldn’t care less,” she said. “Truly—every demon on the frontline is there out of their own volition. It’s like tradition to them. Most parents generally want their children safe, but there are certain tribes where the children get sent out to battlefields to either live or die. That one just happened to die. Tough luck.”

Tradition. That was the word Miss Scarlet chose to describe demonic aggression. Tradition, not nature. It’s like tradition to them. It was then that I confirmed that Sir Tanaka had been right this whole time: that maybe we could simply talk with the demons, had we made the effort for it.

I told Miss Scarlet of my conjecture, but to my surprise, she solemnly shook her head. “No,” she sternly said. “I don’t think that would have worked at all. None of you could stand up to us, see. So we don’t listen to you. It’s like how you need either a show of force or a show of appeasement to talk with anyone from the Ferae. We demonkind only listen to a proper demonstration of power, because the Darklands aren’t kind. We are used to the unkindness.”

The tradition did not come out of nowhere. According to Miss Scarlet, who had lived for probably well over three or four centuries now, it was originally because the Darklands were so unwelcoming, so uninhabitable, that any living creature there basically had only two choices: to run or to survive. Either way, they had to struggle to live. It was so unkind that even the demons who decided to make groups would struggle just as much as the demons who decided they’d make it alone, because while groups kept some threats away, the land was such danger that should the group acquire any resources, they would struggle with dividing it between themselves.

Those who made it alone struggle with larger tasks or fighting more enemies, but anything they obtain would be theirs, and they could chase away or control others with the strength they had to get that resource.

“Have you ever talked with the elves about your history?” she asked me one day. I shook my head.

“Lady Dreyhilda said she’d lived since before the demonkind began widespread invasion, but no, I’ve never talked to her about that,” I said. There was really no reason for this. I simply never found the time, nor did I ever truly think I had any real reason to. Unlike Little Miss Karin with her boundless curiosity, I had to actually allocate my time. Figuring out Miss Scarlet and the demon tradition was part of Sir Tanaka’s grand plan of demonic reintegration, so I’ve planned on talking with her for a while, but the elves were already part of the Alliance and our history was already made.

“Well, you should,” Miss Scarlet answered. “Since you’ve come to me numerous times about demonic traditions, maybe if you understand how human traditions came to be, it will help shed some light to your questions. After all, you’re not only trying to integrate us, are you?”

So I did. I found Lady Dreyhilda in her favorite study room, which she virtually never left except to go in her official capacity as either the Sage of the Ages or as the representative of the Spiritual Faculties of the Elven Societies. The blonde elven beauty was surrounded by countless volumes of books, with scrolls upon scrolls of parchment and paper laid upon the walls—Goddess knows what those are.

To my surprise, Lady Dreyhilda explained even further—she had lived a whole thousand years before the demons began their invasion, before the Demon King even existed. She had been tracking ancient human kingdoms since that long ago. This knowledge did not come for free—Lady Dreyhilda used to be considered a very odd elf since she had an interest in the outside world. Most elves just kept to themselves, which was the reason the Elven Societies was actually something that was only officiated very recently.

Even more so, an interest in humans? The race that could barely do anything without their tools? Lady Dreyhilda’s interest was too queer.

Humans had apparently formed kingdoms by then, but it used to be something very different.

“And not just the kingdoms, too,” she explained as she browsed through several of her scrolls. “See, we elves tend to have so much free time with our lives. So we learn a thing or two to help pass the time, sometimes finding things that tend to stick, and we do this over, and over, and over again. Some of the things I learned still help me today—and one of them was mapmaking.”

She took out what looked like a very old scroll, carefully untied it, and laid it on the table. Her eyes glinted as she pointed to an area that—from the surrounding land—I could recognize to be where the Kingdom of Lenamontis stands today.

There were no names or indications of any sort there. There was only the Loulonge River that went from the peaks of Mons Fluminum, one of the seven mountains that surround Lenamontis. Our biggest cities were built surrounding the river.

I was familiar with the geography of Lenamontis, but even I had to admire the precision of Lady Dreyhilda’s ancient map.

“Just a thousand years before I was born, your kind did not even have kingdoms at all. This was how the landscape used to look like. It only began to change after your ancestors learned to farm. That happened when I was just … maybe a couple hundred years old?” Lady Dreyhilda caressed her map with a nostalgic look. “It was an impressive feat, really. We elves live and subsist ourselves on plants, but never did we ever consider making our own fields and choosing our own crops like you humans do.”

Mankind is a species of tenacity, she further explained. When we hunt, we run our preys to exhaustion. When we fish, we wait for days unmoving until something bites the bait. When we swim, we test the depths we could go to; and when we store, we stock up way beyond what we need, every single time.

It’s the tenacity behind this that led to humans realizing that there are patterns, and that some of these patterns could be controlled. For example, a pattern of how certain vegetables grow together with certain others. A pattern of how some meats are easier to process and taste better when cooked in a certain way. A pattern of how to conquer burdenbeasts so that we no longer have to hunt them down each time, a pattern of when they reproduce … a pattern to nearly everything in life, from the birthing of animals, the growths of trees, to the movement of the stars.

Mankind of the past wasn’t stupid.

And like how certain ancient men developed agriculture to gain an abundance in food supplies, certain other ancient men settled by the seaside to claim all the fish for themselves.

Agricultural lands developed quickly, and soon, mankind began feeling protective over the things they owned. Like always. This was the birth of land ownership, that certain lands are owned by certain farmers, and that these farmers are the owners of whatever the land produced—foodstuff or otherwise. In other words, if other people around them wanted to eat, they had to ask from the farmer. The farmer would then extract their toll by having them toil, making them work the fields, and later giving them their products for compensation.

Slowly, land ownership became ownership of every resource. This went from foodstuff, to animals, to other products, and, most importantly, to people—if you control what the birds feed, you control the birds. Those who are indebted to the landowner had no choice but to follow their commands, and while they had people at their beck and call, the landowner must also be careful that their land didn’t get taken by the very people who served him. This apparently gave rise to the early hierarchies that would later evolve to various other forms of relationships—from chiefdom, to rulership over joint lands, and, finally, to the form of kingdoms as we know it in history.

Apart from cultivated lands, landmasses near the seas also became objects of covet. The best places to store the boat, the best places to hide in case of a storm; the spots nearest to where the fish were plentiful, there were many places near the sea where people wished to make their living. Oh, there’s also the matter of freshwater for drinking.

Places like these were places where kingdoms like the Kingdom of Admari came to be.

I learned recently that the kingdom was much younger than Lenamontis. This was no surprise to me, since Lenamontis was developed on very fertile lands; we were surrounded by mountains of very lush greens and ourselves surrounded the path of a very bountiful river. Our territory also encompassed various dukedoms where crops were rich and farms would thrive, and there was much we could take without hurting the land. Lenamontis was such a desirable land that the original Three Powers—that today became the royals, the nobles, and the judiciary—actually united to defend it.

As you taught me, our military still has three entire branches that serve their original Powers, of course—the Executor Legis, for instance, serve the Magistratus—but it’s mostly a relic of the past. We all trained together to protect the same people.

The Kingdom of Admari apparently had no such standing army, because their land was not necessarily fertile. Not enough to warrant everyone defending it in such an organized manner.

The one thing I do admire from Admari was how they even came to be, to begin with. Admari was a kingdom of traders, who found their share of the land by providing the one ingredient nobody else could procure: an abundance of sea products. While we have mined rock salts, nothing quite beats the taste of oceanic salts; they have numerous jewelries made of pearls, which couldn’t be found anywhere else; and their foodstuff was just brilliant. They discovered preservation spells before anyone else because they could stay out on the sea for days on end, making their catch stay in the open air for much longer than our fruits, which forced their mages to be more inventive. From this, they had traders who helped them carry their products to the heart of the land—these traders later made the sea producers band together and unite, giving slow rise to Admari communities that would one day evolve into the Kingdom of Admari as their trade flourished.

However, due to their roots in trading, they knew full well about how they couldn’t simply trust anybody—not even the kindest of merchants, because merchants will always be merchants at the end of the day. Nobody who sounded too good to be true would ever really be so good they were true, and nobody was an exception to this. Nobody.

Not even the Hero they helped summon.

I suspect that their most recent attempt at Sir Tanaka by means of framing him for the slave storehouse was their comeback after their abject failure with Sir Hector, who used to be Sir Tanaka’s mage before Lady Dreyhilda. In the end, the souring of the relationship between Sir Tanaka and the Kingdom of Admari did not entice the Kingdom to lay low and apologize for what they’ve done to Sir Tanaka, but instead made them distrust him even more. I’m truly not sure why. Would it not be considered idiocy to challenge a literal living god?

I truly can’t see sense in their decisions. It irks me to no end. I wish there was a better way to explain their decisions in a more rational manner, but it would need me to have someone deep inside the Admarian court intrigue, and I unfortunately have no such resource as of the moment.

Maybe that’s why I haven’t been feeling very good, especially in matters relating to the Kingdom of Admari.

I will have to face Rex Lenamontis tomorrow with Miss Scarlet and the messengers from Admari. Miss March, if you read this letter in time, please pray for my success. I fear that my trials have only just begun.

In best hopes,

Charlotte Valeria de Constantia,

Ducal House Constantius, Kingdom of Lenamontis.

*

Please sign in to leave a comment.