Chapter 11:

LETTER 6

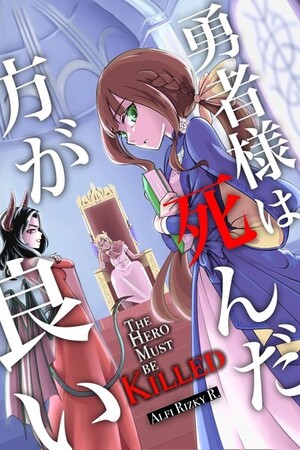

The Hero Must be Killed

Miss March—

The breeze of a new day as we near the start of winter blew cold and harsh, but what made me shudder right now is not the chill in the air or the hint of drying tree leaves as the sky makes way into gray.

Within the month after the hearing, we actually did cooperate with the Kingdom of Admari—although the boatman they captured was especially stubborn. Even more so the moment they saw a Lenamontese soldier, which should probably be a hint for something that I can’t quite put my finger on at the moment. Apart from that, we didn’t find any more clues. The boatman ended up facing criminal charges in the Kingdom of Admari for illegal entry, but he would be extradited after he had finished his sentence.

From the moment he fell silent the first time, until the sentencing, he did not utter a single word.

The frequency with which Sir Tanaka had been disappearing from the Mansion had dropped, notably so. Along with the darkening of the sky and the increasingly chilling air, Sir Tanaka had been spending more and more time at home, and we finally got to talk as often as we used to. Everybody in the Mansion was also happier about his increasing presence: Miss Hari—or Lady Haraldina, as she was better known in the Court—was very excited about showing him her new inventions, fresh from the dwarven forge, which she had begun working on ever since Sir Tanaka made magic forging part of an acceptable march of progress among the dwarves. Oh, Miss Hari was the one who actually created the Academic Transmission technology! The dwarves had apparently long experimented with far-distance instant communication, but their aversion to Magic made progress really slow on that frontier. Thanks to Sir Tanaka negotiating for academic platform, however, we could now communicate virtually instantly to all territories everywhere. It still wasn’t something we could use nilly-willy for daily purposes, but it was truly magical nonetheless.

Miss Scarlet was teasing everyone to Sir Tanaka’s exasperation, as usual, although her pranks had been so much more lighthearted that even we knew she couldn’t have meant any malice. Lady Dreyhilda actually spent most of her time with Sir Tanaka in such a subdued manner, as if she had been wed to him the longest; I couldn’t help but feel a twinge of jealousy.

Little Miss Karin and Miss Cath were playing by the fireplace a lot. Miss Artia stood there, ready to serve her sister and mistress at a moment’s notice, as always. Amelie was busy keeping the house running, as always; she had also been checking whether we would have enough stock of supplies for winter, and Sir Tanaka had been helping her out whenever he wasn’t too busy attending to his betrotheds. Leonie, my best friend and most trusted knightess, said she would only return much later in the evening due to some errand. Funnily enough, Yatzil, Sir Tanaka’s only actual legal wife, couldn’t be around; she also mentioned that the Merkingdom would slow down all activities as winter comes sweeping through the land, as was always the merfolk habit. We should probably check with them after winter has ended.

On my end, I’ve been spending most of my time with Astrid—yes, the Astrid Ermengard von Wehrmann, former First Princess of the Land of Diutiscus, who also escaped from her homeland to be betrothed to Sir Tanaka. We grew close almost immediately after the last Diutiscus royalty fell; while we had no real shared experiences, we knew how it was like to be burdened by expectations. She mentioned to me once that she had always admired how I seemingly never broke, while I replied that I myself admired her courage to leave everything behind and start over. We shared sweets and cookies over a few good laughs, and before I even knew it, we'd been calling each other just by our given names.

Astrid was the person who helped Sir Tanaka negotiate for the freedom of academic platform after his request for the abolition of slavery got rejected. In other words, if not for her aid, Miss Hari never would’ve developed Academic Transmission, and Lady Dreyhilda’s theory of Arcane Arts would never have developed into such a flourishing field in just the matter of months. Even Lady Dreyhilda herself acknowledged as much, and Sir Tanaka was very proud of her for that.

Ah, I wish I could’ve helped him like that. Instead, I was sent here to slow him down.

… no, I probably shouldn’t think of it that way. I’m trying to get him where he wanted, help him achieve what he wanted to achieve, help him shape the world into the future he desired. However, that alone wasn’t enough. He couldn’t shape the world alone, and I have to keep him grounded to the very world he wanted to change; I’m playing my role here.

It just so happened that the role required me to talk with him and convince him to slow down.

Well, at least, looking at the diminishing frequency with which he disappeared from the Mansion to take care of the slaves he helped escape, I could tell that he wouldn’t be so rash this winter. I think Sir Tanaka knew that the likelihood of a slave surviving a harsh winter on their own was incredibly slim. This world was nowhere as convenient as his, after all, and he still mentioned that even in his world, people could die from frostbite in winter if they weren’t careful. If a world as convenient as Earth still had cases of these winter deaths, I could only imagine how much harder it would be for us.

It was by excuse of this cold, and my recent consistent outing as Manus Dextra, that I could ask Suzuki to spend the night with me.

Being the kind man that he was, he agreed.

All in all, we were so busy this year, and we barely got a chance to really talk with each other apart from small pleasantries and stolen glances in the Mansion. As we tucked our blankets and headed to bed, with our faces red and our hearts thumping to a very loud dance, we began with nervous small talk until the lights were finally turned off.

As we fell silent, Suzuki hugged me from behind. I figured that the comfortable silence was a good place to start. “Suzuki….”

“Hmm?”

“Please don’t get me wrong,” I said. “You know I support you, and I fully agree with your idea for a more equal world.”

I wasn’t lying. I also wasn’t the only one. Astrid had no qualms about losing her status as royalty, and she had fully come to terms with the fact—she tried so hard to be self-sufficient, even with what limitations she had, even with all the support behind her back. In a similar manner, I understood that my dukedom was something I inherited, not gained out of merit. The dukedom did not come upon my lap because I prepared for it; it was the other way around.

If I had to lose my nobility for Suzuki’s world to become reality, then so be it.

Suzuki nodded. “Yeah.”

“But …,” it’s difficult to put it into words. I gulped. “But what do you think … what do you think will happen next?”

I turned around to face him. Our faces were mere inches away from each other. I couldn’t help but draw a sharp breath.

“We’re protecting escaped slaves. That’s technically illegal, but I know you won’t be caught, and I love you too much to turn you in. But….”

I let my sentence trail a little as I caressed his face.

“… but what comes next? The slaves are growing bolder. And, while seeing them desire freedom is a good thing, I just can’t help but wonder. What happens next? Will there be war? Again, so soon?” I drew a sharp breath. “Even I find you oddly adamant this time around, Darling. What happened? What are we looking at here?”

Suzuki gave me a very gentle smile … and very sad eyes.

“I … had a sister,” he started. “She was five years younger than I was.”

Suzuki began his story. Back on Earth, even without nobility or slaves, social classes still existed—between those who could navigate their surroundings and those who could not. Between those who could follow trends and those who failed to. Between those who were common men, and those … who were, in a manner of speaking, more queer.

Suzuki was often the latter.

Ever since he was very young, Suzuki was a child of the books. He would read materials beyond his age, fiction with words he barely understood; he would find himself an empty corner with a whole stack of books, and he would devour them all in one sitting like a hungry beast.

When his friends played around, he would travel to and fro the library, finding solace amidst his loneliness that he was accompanied by the minds of so many others, poured over the countless volumes of books that he tore through with his youthful curiosity.

However, this meant that Suzuki was an odd one out. And his country, as it turned out, was not particularly fond of such oddities.

By the time Suzuki hit younger compulsory education—a level he called ‘second grade’—the other children began picking on him.

At first, it was his smaller belongings. He would lose his eraser, a stationery tool used to cancel writing from graphite sticks called pencils. He would start losing his pens. Then it escalated from there. He would lose random trinkets in his bag. He would lose his shoes. Sometimes, he lost entire books, even those he borrowed from the library.

More often than not, he would find those things again—but they would always either be out of his reach or severely damaged. Suzuki had to pay fines to the library for ruining the books he borrowed, and this money had to come out of his parents’ pocket.

Finding out from that, his parents lodged a complaint with the education institution regarding this issue, but that only made things worse. It got so bad that, by the time Suzuki hit fifth grade three years later, they had no choice but to move away.

His younger sister began compulsory education soon after.

In his new school, with no prejudices tied to his name, Suzuki actually adjusted much better. He found friends with common interests, joined the literature club in his school (he’d told me before that education institutions on Earth afforded extracurricular activities, but each time I think of it, I just keep being more and more impressed. It’s as if they’re educating their young to be polymaths of old!), and in general found a place to belong. Suzuki was finally thriving, away from the pain he suffered from his childhood.

His sister, however, was not so lucky.

Nobody was sure how it began. She never even told him, and for good measure, his parents. Apparently, the bullying—the phrase they used for particularly severe cases of picking-on like what Suzuki and his sister suffered—was different from what Suzuki went through, enough that it didn’t leave a noticeable trail for his parents to notice.

Suzuki, however, noticed. A victim would recognize another victim anywhere.

“However,” Suzuki’s voice quivered—I noticed the lights in his eyes quivering with his voice as his tears began to form, “I turned a blind eye. I pretended I didn’t notice that. I … I was afraid. Whenever I saw her return with that look on her face, with unnatural wetness on her shoes or slightly messy uniforms, I would be reminded of the kid that I was: the kid who suffered the same.”

The memories of his time were so severe that even just looking at her sister would drive him mad with fear, and it just fed onto his guilt. Day by day, night by night; as years went by, Suzuki would only find himself cornered by these two emotions.

Then, one day, it happened.

He finally saw firsthand his sister being bullied.

He was walking home with his friends when he saw his sister just across the street: it was a busy way for cars, the horseless carriages I’ve mentioned before, but he recognized her as they started the day together.

Her bullies threw her into oncoming traffic while laughing.

Suzuki said that it could’ve been a mistake—maybe they just wanted to playfully push her to intimidate her. He couldn’t be sure. All he knew was that, all of a sudden, his sister was directly in the way of a very large truck, which did not have the time to slow down.

Finally, Suzuki acted before his mind could wrestle with his feelings.

There was no fear. There was no guilt.

There was only the rescue of his sister.

He pushed his sister out of the way just in time—but that was where his consciousness ended.

“By the time I opened my eyes, I was with the Goddess,” he concluded, tears flowing down his cheeks. “I’ve ignored my sister’s suffering for so long because I was a coward. Then, just when I finally did something right and brotherly for once, I made her witness her own brother die. Was she happy? Did she feel guilty? Did the bullying stop? How did my parents feel? How did she feel? I don’t even know. I’ve died on Earth. The Goddess said that’s why I could be sent here.”

Before I even knew it, I was sobbing even harder than he was. “I’m sorry,” I croaked. “I didn’t mean to—”

“No, Charl,” he said as he hugged me, caressing my hair very softly. “It’s okay. I’ve wanted to tell you this for so long. It’s like a burden is gone. It’s nice.”

All this time, Suzuki had had very strong feelings about oppression. He was probably still recovering from his own fears, now that he finally had the power to fight back. It was probably why he identified with the commonfolk.

It was probably why he reacted against that one slaver with such a harsh response when he first began his journey.

He was never over the guilt of abandoning his own sister.

“So … if you ask me what happens next, I don’t know,” he admitted. “I want the slaves to fight back. I admit that. I also really don’t want any violence to break out. Unfortunately … I don’t think that can happen. Like, at all.”

“Why?” I asked. “I can negotiate with Rex Lenamontis if I must. We can figure this out.”

“That alone won’t be enough,” he said. “My days of reading opened my mind to the history of the people on Earth. We did have a very long time in our history when slavery was common, you know. But then, one day, it finally got all ruled out….”

“So that means your rulers—”

“… because of bloody revolutions.”

I paused. “I’m sorry?”

“Charl …,” Suzuki awkwardly avoided my eyes. “We had wars. Lots of them. Slaves revolted, everywhere, throughout history, around the world. It was thanks to two particularly violent revolutions that slavery was finally outlawed in basically all countries. Even then, of all those wars, only one was technically a successful slave revolution—and the atrocities committed there were horrifying, even for the time.”

He went on to describe what he called the ‘Haitian revolution’—the name of a country on Earth, as it turned out, that would be the only slave republic in the world. Even before the revolution, tensions there were particularly harsh, so much hatred had coalesced, that when additional pressure was applied from a greater country outside that subjugated them once, they retaliated in full force. Blood was spilled: men, women, children. People were beheaded, their heads fashioned atop sharp pikes and displayed so that all other oppressors who came would find their hearts stricken with fear. The slaves would cleverly use traps and terrain, relying on the sickness that their oppressors couldn’t handle to drive them away.

Bodies would pile up like mountains, and they would not clean them so that the next wave of oppressors would know exactly what they would come to face should they choose to stay and try to fight their way back in.

Even innocent people were not spared: many were killed just simply because they were affiliated with the oppressors, something as simple as sharing the same skin color.

Worse yet, in their attempt to scare the slaves, the oppressors that came in to subjugate the rebels did much of the same—if not worse.

In the end, both sides drew the absolute worst out of everyone.

Suzuki mentioned that this was not taught at school because it was virtually irrelevant to his country, but the first time he read about that, he felt that he understood. Somebody had to fight back, and fighting back isn’t a pretty thing. It could easily get violent. It could easily get bloody.

Things could easily devolve into a whole war that cost innocent lives.

They were free at the end. They inspired other slaves, too, to fight back. But at what cost?

That night, instead of falling asleep calmly as I usually did in Suzuki’s embrace, my eyes refused to close exactly because of one thing: abject terror.

In a world as advanced as the Earth, even slave revolutions took thousands of lives, with countless atrocities committed on the battlefield.

If a world as convenient as Earth still had cases of these brutal deaths, I could only imagine how much harder it would be for us.

Miss March, I’m growing desperate. I truly can’t see a bloodless way out of this. I beg of you, please, please help me. A single word would do.

Please tell me what I must do to avoid another war so soon after our war of a thousand years just ended.

My prayers,

Charlotte Valeria de Constantia,

Ducal House Constantius, Kingdom of Lenamontis.

*

Please sign in to leave a comment.