Chapter 13:

LETTER 7

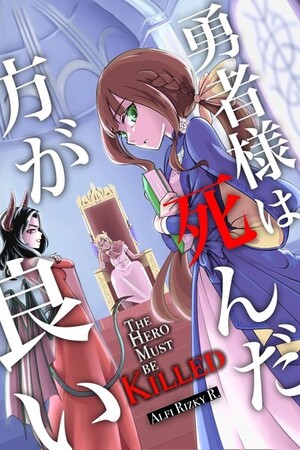

The Hero Must be Killed

Miss March—

I truly can never fathom how even just a single word from you could be so powerful.

I discussed a little bit more about how slavery was ended on Earth with Sir Tanaka. Snow had finally fallen, so we had a lot of time to just sit down over warm drinks, with sweets shared, to simply talk. I am most grateful that Sir Tanaka was a very prolific reader during his time back then, because otherwise, I don’t think many would’ve been able to answer the questions I had.

We skirted around the topic of the bloody revolutions, but I learned that even behind the war lines, a political battle was being fought. The rising anti-slavery sentiment was the core cause that kept preventing too many of the oppressors’ army from being sent to the frontlines at any given time: their resources were limited, the slaves’ nation was full of sickness that the oppressors couldn’t recover from, and the popular notion in the army was that being sent to the frontline was a death sentence. This, compounded by the public sentiment regarding slavery, made the rulership a lot more hesitant to supply military support to retake the slaves’ republic.

This kind of discussions was actually one of my first suggestions to Sir Tanaka, way back then when the slave merchants’ quarters began getting mysteriously attacked—in an offhanded manner that wouldn’t rouse his suspicion that I was aware of his secret activities, I suggested that he use his academic platform to print discussions regarding slavery.

We didn’t have a lot of literature on slavery. When Sir Tanaka asked me why, I could only answer that it was simply how things had always been: slavery is basically turning your body into something that could be measured in terms of gold. When you need money, or when someone needs you to make money, you become a slave. Your body becomes a commodity, and whoever sold you gets the money. You could be enslaved because you lost a war, you could be enslaved because your family desperately needed the money, you could be enslaved to pay a debt, you could be enslaved as punishment … you could even be enslaved simply because someone kidnapped you one day and sold you to a slaver.

While Lenamontis had tried enacting Regulations against that last practice, if you know the right slavers, you could oftentimes get away with it. The Executor Legis were still human, after all, and human lives have human needs.

We never really saw what’s wrong with that. It felt almost natural. It really wasn’t until I started seeing Sir Tanaka’s passionate dislike for slavery that I began to think more deeply about it. So why would we have literature about slavery at all?

In the end, we managed a very fruitful series of discussions—talks about the nature of human dignity, about the dangers of commodifying without limits; about how laws that protect the layman could not protect servants, let alone slaves; how the stripping of rights was done deliberately, but often to the wrong effect … how slavery wasn’t ‘simply how things had always been’ because everything must have a beginning and a reason, and more importantly, the fact that what had been is not always what should be.

I suggested that we publish a small study on the thing. Sir Tanaka said that there was a discipline on Earth called sociology, a field that specifically studied the dynamics of mankind in groups, how humans interacted with each other, how they formed culture, civilization … everything about the social form of humanity. On that basis, I asked him if we could at least formulate a simple background for analysis, even if surface-level—something that’s at least just enough to get people talking.

Especially those who found academic pursuit to be a matter of prestige.

Along with Lady Dreyhilda’s publication on the Arcane Arts, Sir Tanaka began publishing on slavery.

“Back then, in school, we had to do essays like this almost every week,” he said once while writing his paper. He laughed. “I can’t believe I get to actually make good use of it.”

Children of Earth must be so advanced. I couldn’t imagine being so young and having to write such detailed papers on the weekly.

The paper spread rather quickly, as was the platform’s intended function, and the response was almost equally fast. Our ninja squadron had never been so busy before—assassins, kidnappers, mercenaries, harassment on the streets to the point we couldn’t send our maids and butlers on errands without at least two ninja guardians … a lot of people weren’t particularly happy with what Sir Tanaka had to say. People with enough money. Truly, had it been anybody else, everything would probably have ended at this point.

But we’re not anybody else.

In fact, the continuous clandestine attacks went so predictably that we had resources to spare. In order to strengthen his argument, Sir Tanaka required data on the reasons people were enslaved, and there was nobody else we could send who could do such a menial task without having to fear retribution other than the clandestine ninja squadron. At one point, we had to send nearly the entirety of the squadron if not for Miss Hojo’s own insistence to at least maintain three ninjas around the Mansion just in case. Sir Tanaka offered to put everyone on a Barrier lockdown—Barrier being the Miracle he used to prevent the entry of anything unwanted—but both Aeolius and Amelie, our chief butler and head housekeeper respectively, warned that it could possibly hinder the secret open notice we had for slave sanctuary. Somehow, we juggled through that just fine, as well.

All in all, the data gathering for the papers went well, and Sir Tanaka went on to publish a few more papers.

Since we didn’t have the field of sociology yet, most of the replies to the paper were mainly attacks addressing Sir Tanaka’s idea that slaves were ‘inessential’.

“It was, in fact, with such manpower as the one provided by slaves that our country has held on, and it is with their service that the country will stand!”

“But is it still service when the labor was done involuntarily and without compensation?”

If anything, I feel like they missed the point when he said slaves were inessential—he was saying slavery was unnatural.

We discussed again the history of the kingdoms with Lady Dreyhilda, and we found a pattern: slavery only started existing after land ownership, where labor was scarce but work was plenty. Apparently, the further back we went in history, the less and less we found occurrences of slaves—even slaves as we have it right now only entered written records around the founding of the united military of Lenamontis, and it was only a passing mention. There were no mentions of slaves anywhere before that.

Slavery, Sir Tanaka argued, was not a system that just appeared out of nowhere. Like all else, there was history to it, and like all that was history, that could be changed.

While the nobles were talking about whether they’d have enough manpower to keep their territories running, the commoners were talking of something else entirely.

“We turn criminals into slaves for punishment,” a representative for the Court of Plebeians wrote. “It is a most effective deterrent, given that their misdemeanors must be paid through the use of their very time; it is a humbling deterrent, as they would have masters they could not disobey; and it is a fair punishment, as it forces them to repay their evil deeds through service.”

Afterwards, they went on a rant about how dangerous it would be if slavery was abolished. It would be a criminals’ galore, they said, as the criminals sent to slavery would no longer have any means of control.

“But isn’t that punishment virtually just the same as community service?” Sir Tanaka wrote back. “You would put a dysfunctional member of a society under heavy restriction, and assign to them a bare minimum of achievable return to give back to their society before they could be pardoned. That’s simply community service. Harsh restrictions and strong monitoring would have sufficed—no need to place them under the same systemic issue that is slavery.”

Besides, it’s virtually impossible for a criminal slave to find pardon. It’s to the point that the Regulations actually don’t mention much about crimes and slavery, apart from acknowledging the submission into slavery as a legal punishment and stating that a freed slave is cleared of all their former crimes. Community service would be a more humane, while still equally restrictive, form of punishment—also, rather than only being meritorious to those who could afford to buy slaves, it would benefit the community more as a whole, while also allowing the criminal to repent and be reintegrated into society.

Not to mention, he added—and this is where the data from the ninja squadron came in handy—the number of slaves who were sent to slavery for criminal reasons numbered extremely few. In fact, they were the smallest slave pool, comprising only approximately two people for each hundred slaves.

The next smallest pool was the money slaves, who were sold by their families in exchange for cash. Then, in order towards the greater pool, it went from debt slaves, war spoils, and—finally—subjugated slaves.

War spoils were people from enemy camps in a formal war who were captured and sold to slavery. They may also include their family members, which was why their numbers tended to be inflated.

Subjugated slaves, however, were slaves captured by mercenaries from nearby isolated tribes. While the tribes had little contact with other civilizations, some slavers made a habit of hiring mercenaries to go to their societies, kidnap or capture a sizable number of their members, and these people would be resold as slaves. Since the tribes weren’t part of Lenamontis, or even any other kingdom, for that matter, this subjugation carried no real legal risk. As the tribes recovered their numbers, the mercenaries could always raid those societies again, like a farmer harvesting their animals.

The slavers virtually gained infinite returns.

In other words, the Court of Plebeians truly had no reason to worry: there were many other punishments available for various forms of criminals, Sir Tanaka argued, while there is a significantly large number of slaves who were there from causes beyond their own control. Not for failure of the rulers to protect them, not for failure to prevent the sudden inflation of debts that could not be repaid, but from the deliberate attempt to capture from people who were simply living their lives in their isolated tribes.

This academic back-and-forth kept going for a while, and it was frankly a fascinating affair. With the lack of formal social studies, all we had were really grounded worries with a little sprinkle of perspective on ethics and general idea of how things ‘should be’, which could immediately be dismantled and studied under a looking glass. The polymaths of old used to do these in forums and debates, as stone records from the Heliodorus Republic heavily showed. It’s refreshing to see this kind of intellectual challenge, now international and public, very much alive.

The best part about this publication was that Sir Tanaka engaged in dialogue. He got people talking. He made nobles start to discuss slavery in their times off; he made fair ladies and well-dressed maidens discuss the rights to humanity when they were having tea; he made agricultural nobles and trade nobles argue at length about the merit of keeping slaves during their little business negotiations. His discussions permeated the life of the nobility, and the nobility dictated the lives of the people in their territory. Soon, with the academic discussions being truly freely accessible to anyone, the commoners who could read took to leading the discussions as well among the rest of the communities.

By the time the attacks on the compounds escalated, we already had a large split of opinions across the entire Kingdom.

And, by your advice, it was on this wave that I rode my suggestion to Rex Lenamontis.

“It’s called indenture,” I explained my proposal. “I will pass bills on Constantius that wouldn’t outright prohibit slavery—that change would be too sudden, too radical. I want to create a … a transient state, so to speak.”

“And what form would this take?” He asked.

“A slave in Constantius will be considered indentured—they will be tied by contract to a single master,” I said. “They will have to perform services for the master and obey this master’s command within reason and ability. They will be compensated, but by minuscule amounts—just enough to scrape a living by.”

“Isn’t that virtually the same as slavery? Apart from the compensation, maybe.”

“In practice, yes. But the compensation should help alleviate the ethical dilemma about keeping slaves. And,” I paused a little, letting the King know that the puncher was coming, “all indentured servants cannot be bought or sold.”

The King contemplated for a minute. “In other words, by means of indenture, you wish to eliminate the notion of slaves as goods.”

“Correct, Your Highness.”

“And by locking them to a single master, you are forcing the masters to be responsible for the well-being of the slaves, making them a resource that couldn’t be taken for granted?”

“And I wish to make this feel tangible by means of exchange through the compensation. When they pay the compensation, they will realize that they’re not dealing with goods or animals. They’re dealing with fellow human beings.”

That was the quickest solution I could come up with. The transition should be bloodless, the slaveowners shouldn’t be too angry since it didn’t really touch upon their slave ownership, the anti-slavery should find the increasing humane treatment on top of slave protection laws a step in the right direction, and there should be generally less tension in the meantime.

“Afterwards,” I said, “we think of how to transition to abolition entirely. We can use Constantius for our experiment. Constantius is a melting pot for people of various stations and backgrounds working together for the greater purpose—they’re used to differences and they’ll adapt quickly.”

It took no time at all for the King to agree to the proposal. I had to return to Constantius to write the bills necessary to enact the change; my legal advisors still resided at my home back in Constantius, so I needed to go there because I needed their help. Sir Tanaka was kind enough to teleport me right back home to get the bills quickly drawn up.

In only one week, complete with the King’s approval and everything, I managed to enact a whole new rule that changed the face of slavery entirely in Constantius.

I was not ready for the slaves’ reactions.

They cheered.

I think I should put this into perspective. In Constantius, being the very frontline that bordered the Darklands, we depended on each other to survive. When someone’s house was destroyed, we all picked up our hammers to put it back up. When someone was hurt, we all carried them home and called the physicians to get them healed. When we cry, we cry; and when we laugh, we laugh. Constantius had always had little care for one’s station, except when it comes to the chain of command, out there on the battlefield. One’s station does not make one’s qualities, and Constantius needed this quality more than anything else.

In Constantius, you are what you make of yourself, regardless of where you stand in society.

In other words, Constantius had always been a relatively better place to be a slave: technicalities of being a slave aside, the people have always seen slaves as fellow human beings; as friends, or even as family. The introduction of the indentured servant system only tied the already friendly bonds into something formal. A lot of the masters hugged their slaves, and the slaves cheered with one another. Somebody treated everyone to a drink in the local taverns.

That night, everyone became one.

This was only a steppingstone, only a transient state, a transition; I couldn’t imagine how beautiful it would be when we’ll finally see the day all men are truly free.

With highest hopes,

Charlotte Valeria de Constantia,

Ducal House Constantius, Kingdom of Lenamontis.

*

Please sign in to leave a comment.