Chapter 3:

Chapter 3

Broken Realm

Two and a half days ago

Castle Guraud

Kingdom of Yvon-Rier, March of Ris; Troude Continent

8 am, Elven Year 132, Seat 7, Olnday

The soft breeze was cold, but warmer than the previous days. It was a sign that the Hied months were ending, a sign that the rivers would soon flow, and a sign of strife. Hulbar Riswald stood on the loggia overlooking the steep descent of the mountains. He took a deep breath and let it out, watching the condensation dissipate into the winter air. Below him, he could hear the chatter of the castle guards, its footmen, and his daughter. He watched her, brimming with excitement as she prepared herself, armour and all, for another scrape of the woodlands. He sighed and rubbed the bridge of his nose.

There was a soft thud to his left, and when he turned to look, he met eyes with his wife, Elva, who smiled at him. Hulbar smiled back, and when she came to press her hands on his chest, he gave her a kiss on her forehead. Elva turned to look down the mountain, her eyes eventually landing on their daughter.

“Is she off?” she asked, her arm now wrapped around her husband’s waist; his was the same.

“Soon, I think. I told her last night to bring her brother with her, but she insisted otherwise,” he replied, ever so slightly furrowing his brows.

“She will be okay, you know that. Besides, Sindor has never been a fan of early mornings,” she said, looking at him. He huffed in response. There was a lot on his mind, he knew the Riswald crest had a duty to uphold, to hold the border. He knew it since he was a boy, since the word ‘frontier’ became ingrained in his mind. Yet he found it still difficult to watch his children leave the castle gates, into the forest, subject to only the gods know what. He sighed and turned to his wife. She smiled, and he did too.

“I think a kiss and some breakfast would ease my nerves,” Hulbar said, a wry smile on his face before turning to his wife, lips puckered. Elva laughed, smacked him on his chest and gave him a quick peck on the cheek before walking down the other end of the gallery.

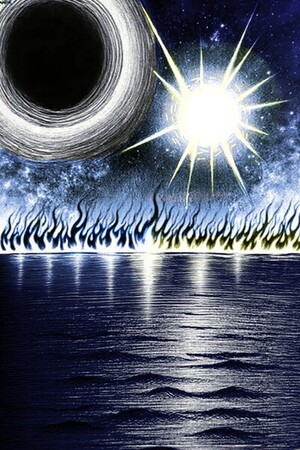

“You better hurry love, the cooks were up earlier than normal this morning and - “ she was interrupted by a loud, thundering boom in the sky, one that split the clouds right before their very eyes. There was the initial impact of the noise, then a deafening crack followed soon after, like a meteor of the end times. Hulbar and Elva winced, their Marks glimmering. Hulbar’s eyes widened. He turned his hand and stared at the Mark on his open palm. It was hot, searing even. Elva returned to his side, her cheek a glowing white. She was confused, he could see it, but she also knew that he had no answers.

Looking back down, the chatter had stopped, and their daughter, Yves, like many others, stared into the sky. Even from the distance, both mother and father could see the Mark glowing on the back of her neck. Questions reeled through Hulbar’s mind, his eyes frantic, scanning the clouds when - there.

He saw it, a figure descending from the sky. He expected wings, the fiery flames of a wyvern, but no. It was small, too small, almost a speck of dust in the air. There was a barrier around the thing, thin and vivid, but he could see it. Before he could try to recognise what it was, it crashed into the forest, loud and hard. The trees shook from the sheer force of the landing, and despite them being hundreds of metres tall, he could see smoke and snow rising past the branches.

Hulbar was quick. He leaned over the stone barrier and yelled out to his daughter.

“Yves!” Hulbar bellowed. His daughter turned to look up, a concerned but determined look on her face. “Go!”

She nodded once, and, saddle be damned, mounted a horse and darted out of the castle’s gates.

Matisse stared at the gaping hole he, though still finding it hard to believe, had left on the canopy of trees. Better yet, what the hell is that? Was that me? He turned back to the ground, a crater, the width of a school bus just under him. He was at a loss for words, blinking hard, trying to see if maybe the landing on the base of the stairs had jarred his vision to no repair. There was a sudden gust of wind, cold wind, and it felt exactly like that time he was staring at the castle. However, it felt tangible, like he could move it around, push the wind even. Before that, where am I?

Slowly but surely, he pushed himself up, careful not to stretch just in case he had broken anything. Once he was upright, he stood still for several seconds. He looked at the crater he left on the ground, cartoonish almost, but definitely a crater. Nothing hurts. Why. Why does nothing hurt?

He patted himself down, moved his elbows and knees, his neck even. Nothing. He fell several hundred feet from the sky and nothing hurt. He smiled at himself, impressed almost, when he realised that what he was standing on was snow. It was cold, wet snow. It wasn’t the base of the stairs. It was snow. He recalled being amazed at the crater, at the towering trees. Why were there trees? Wasn’t he in class? Wasn’t he just walking down a flight of stairs? Sure he fell, but, why was he there?

Convinced nothing was broken, Matisse took a step forward, cautious of disrupting whatever dream state he was in. Was it something like that time in Tobias’ apartment? Was he hallucinating again? Then, he turned to look back up at the trees, and that’s when he noticed it. Why can’t I see where they end? It was a dream, he was certain now. Much more certain than he had been on anything in his life. He took a few steps out of the crater, his shoes, which, be damned were almost spotless, crunching the snow beneath him. If it was a dream, then it was real, much too real. Matisse felt his adrenaline subside, and he thought to himself that that was a good sign, maybe he did break something, and maybe the pain would bring him back to where he’s meant to be.

He felt something else instead. His cheek began to ache. He stared blankly on the ground. Matisse brought his hand up to his face and rested it on his right side, the same side that Simone had thrown the pencil case at. It was as if he was pinched in an attempt to realise his mind back into the real and current world. The only difference was, the towering trees, the biting cold weather, and crater he had left was Matisse’s world now. That was the real and current. It wasn’t the classroom anymore, nor was it Tobias’ apartment, or his.

The current was the sudden rumbling of the ground, the shaking of the trees, the guttural feeling of impending doom. Something was coming. Matisse shifted on the spot, looking between the trees for something, anything that his eyes could make out. He didn’t know what it would be, but there was something telling him to run; and so he did.

Her arms ached.

It had been weeks since she had ridden a horse, much more one without a saddle. Yves hovered above the horse’s back, stance thin and slim, the air wrapping around her. Her breastplate was loose, the leather straps on her back only half fastened. She cursed, looking over herself one last time to see if she had missed anything else.

As her right hand gripped the reins, her left hovered next to her, spear out, its tip glistening in the dappled sunlight. She could feel her Mark glowing, she could feel it burn through the wisps of hair on the nape of her neck. Yves couldn’t remember the last time it had felt that way. She pushed the thoughts out of her mind and focused on manoeuvring through the dense shrubs.

Then, she pulled her mare to a halt, stopping next to a crater, as a large as a castle’s single door. She studied it for a moment, and when she felt no ilyum lingering, she turned to look eastwards.

“There you are,” she said, almost smiling despite herself. Taking one last deep breath, she snapped the reins and bolted down the hill.

Matisse had cursed more in the last five minutes than he had in the last week, as his sneakers’ soles did little to protect his feet from the crumbling rock and mud of the hill. Running up was horrible, but running down was worse.

He could feel his knees buckling, his chest heaving what air he could manage as he slipped and fell down the slope. He was in pain, but he could feel something coming, something bad.

I need to get out of here, find a river or something and - his train of thought was interrupted when he heard a loud crack behind him. Matisse slipped on a slope and crashed on his stomach. The decline of the hill wasn’t too steep, and he used the low bushes and weeds around him to cover himself. He took three seconds to catch his breath, peering in between the specks of green before he saw it. A large trunk was making its way to him, and, at first he wasn’t sure how. Maybe it was the lack of oxygen? Maybe he was hallucinating? Are hallucinations inside another hallucination even possible?

Then, he realised that he was very, very wrong. The tree, the towering, ten-storey tall chunk of wood, leaves and death, was falling down the hill. It was falling, and it was heading straight to him. Shit!

Matisse scrambled on the snow and mud, his shoes slipping. Panic was setting in, he could feel his heart beating through his jacket. He looked up, and this time, he could hear all of it. He could hear the snapping of branches, the roar of the trunk, the croaking of the other trees around him. Finally stable on his feet, he pushed himself to his right as the tree made contact with another branch above him, raining twigs and fruit he had never seen before down on his sides. He had barely made it out as the tree connected with the ground, a bellowing crash that stung Matisse’s eardrums.

Covering his head, he stumbled onto his feet and began his descent once more, this time, much faster. He tried to ignore the chaos and pure path of destruction the tree to his right had left, and continued to leave as he pushed downward. He wasn’t sure if the natural calamity that chased him was over, but he wasn’t taking any chances. How the hell did that happen?

Looking back, he saw nothing, even as his eyes, to the best of their ability, scanned through the opening the fallen timber had left. Taking leaps down the hill, that was when he saw it; sticking out of the fallen trunk was a long, glowing stick. Only an added five seconds of hesitation made him realise it was a weapon, a spear to be exact. A spear? What the hell is a fu -

Pain.

Just as Matisse turned his head for one last look behind him, he saw it - no, he saw her.

His eyes locked with a girl’s, her blonde hair levitating in the air as the heel of her boot connected with his right side. He saw her face, one of anger, brows furrowed and teeth bared. Matisse could feel his ribs crack, he could feel himself crumbling to her sheer force, but there was something else. He could sense it almost, and it was faint. It was as if her foot was laced with something, something that churned his insides, that turned them upside down and into themselves. It made him sick.

The next thing Matisse felt was air, just like when he fell from the sky. He was spiralling and he realised that the kick to his side had sent him hurling down the hill. The force had propelled him not onto the ground, but a few feet above it; instead of crashing down the hill, he was adjacent to it, almost like a horrible math problem.

Airborne for what felt roughly fifty metres, he finally made land before his shoulder connected with harsh snow, causing him to spin violently. He rolled, hard, on soil and rocks. He tucked his chin to his chest as best he could, as finally, he crashed onto the base of a tree.

He was winded, out of breath, and was only hoping his ribs hadn’t punctured his lungs. He was surprised he was still alive; then again, he did fall from the sky. Face down on the snow, the adrenaline subsided, and it was then that he could feel the waves of pain flood through his body. It was everywhere, his feet, his knees, his sides, his neck, his arms, inside his chest, his lower back. For the first time since he had fallen from the heavens, he cried out in agony.

No thought could be formed in his mind, no words could escape his mouth. From the corner of his eye, he saw the girl land on the snow, barely a stone’s throw away from him. She wielded her spear at her side, and she walked towards him. Was he going to die? He tried to move but it felt like every single bone in his body was bent in the wrong direction.

What - what the hell was that? Even his thoughts felt like a mess. Matisse tasted blood in his mouth. It trickled onto the snow and pooled under his cheek. He tried to push himself up, and in his periphery he could see his right arm moving. He tried to place his palm on the snow and push, but his wrist gave way. His shoulder was off its socket and he managed a small croak of pain.

Matisse coughed, blood gushing out of him. Not just from his mouth, but from grazes, cuts and punctures throughout his body. He didn’t know where, he didn’t know what to do. His mind was fading, his eyes flickering.

Then, he felt it. His cheek. Not the one that took the brunt from the pencil case, but the other. He felt it burn. He felt it melting the snow beneath his face. His mind scrambled for an explanation, was the kick he felt from the girl earlier causing this? He began to hyperventilate, his chest - wait. My chest… it doesn’t, hurt?

The girl stopped just a few metres from him, for what reason, he didn’t know. Matisse felt strange, he felt himself, his bones, his insides rearranging themselves. He didn’t move, but before he knew it, the pain began to subside. His right shoulder, a limping mess just moments before, had snapped back into place, painlessly.

There was a silence, the first Matisse had felt since he had fallen down the hill. He could hear the girl’s boots crunch under the snow. He could hear the birds flapping their wings, their chirps echoing amongst the trees. It was peaceful almost, if he hadn’t been launched by the kick that is.

“Wirte smibny liobn?” The girl finally spoke, stopping just a foot away from him. Except, Matisse was dumbfounded. The words that came out of her mouth sounded like a verbal mockery of English, as if someone combined every singly Eastern European language and dialect into one. There was no intonation, no sign of an accent, it was almost as if he was meant to understand it.

Matisse stayed put. He was better - no, better, than better. His wounds weren’t just healed, they were gone. His rib cage which he thought to be broken had pieced itself together, and blood ceased to pour from his mouth. The left side of his face still emanated heat, it didn’t sear, it was more, warm.

“Wirte smibny liobn?!” She repeated herself, this time with a sense of urgency. He twitched and turned his head to face her, doing his best impression of a man close to death.

He saw her, really saw her, for the first time then. Her hair rested just past her shoulders, the front in strands as the top half was wrangled into some sort of bun he couldn’t make sense of. Her eyes were sharp, a deep jade that had a permanent furrow to them. Matisse thought she was pretty, pretty dangerous.

“I’m - I’m sorry I don’t,” he stuttered, trying to remember from the movies on how a dying man would sound like. “Understand.”

The girl clicked her tongue and sighed. She turned to look around her and Matisse debated a chance of getting away. Before he could even decide, she swung her spear to her side and he noticed something building on its tip. A sort of glow had begun to gather, a strange, reddish culmination of what could only be explained as fire.

“I said, what is your name?” The girl, in perfect English, repeated herself for the final time. Matisse knew this because the tip of the spear, now dripping with wet, liquid-like flames rested just inches away from his face on the snow. He wanted to gulp, but he was more enamoured by the fact that he now understood her. Even more, he was wondering why he couldn’t feel the heat, despite the snow around his face melting, and the grass, wet with mildew, had begun to catch fire.

Nothing made sense to Matisse, everything from him falling from the sky to being kicked and surviving a comically large fall. The girl who looked like something out of a high fantasy novel mixed with an artist’s best interpretation of a highlands woman; and the spear that was basked in flames that refused to torch his face. Nothing made sense because even though he knew his body was in shambles after the fall, it had fixed itself, through divine intervention, luck, or the blessing of Mother Earth. Nothing made sense because at that moment, Matisse could feel tension on his cheek. He could feel it bursting with heat, one different from the spear in front of him.

Then, Matisse felt pressure. He felt pressure building on his once dislodged right shoulder. He felt it move from down to his elbow, then finally, to the centre of his palm. He felt the pressure mounting, as if it wanted to tear at his skin and escape. Matisse wasn’t sure why, but he felt an urge to raise his hand and point it, flat-palmed, at her chest.

“Matisse,” he garbled, finally lifting his head from the ground. At the same time, every so slowly he lifted his arm, and, just as he thought he would, faced his palm towards her chest. “And go to hell.”

There was a sudden release of power, and the next thing he knew, the girl was in the air, a deafening, baritone roar pushing her away from him.

Please sign in to leave a comment.