Chapter 66:

Chapter 66 Lines We Draw

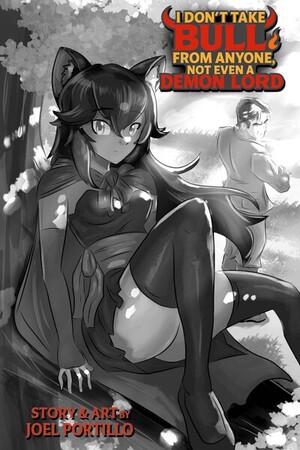

I Don’t Take Bull from Anyone, Not Even a Demon Lord

They waited. Days passed like stones.

The inn sat apart from the town, near enough to see the gate and its guards in the distance, far enough that the city noise bled thin by the time it reached Helena’s Inn. Wyvern-carts came and went on the road, more of them each day. Men with hard eyes. Women with their mouths set like blades. Families carrying more than they could pull. Everyone going somewhere that was not here.

Bellenfort had turned mean. You could feel it in the way travelers kept their voices low, in the way beastfolk hugged the ditches and moved when told without looking up. Word came in pieces: Adventurers’ Guild pressuring merchants, city watch looking the other way, relocations “for order,” fines for whatever they could name. No one had anything good to say. They said it quietly anyway.

Helena took on extra work. So did the girls. They moved like they lived here now—wiping tables, refilling mugs, carrying plates, dodging hands that reached too slow to be accidents. Helena’s look could freeze a drunk at ten paces, but people grew brave when they thought a town stood behind them. Even out here, with trees for neighbors and no guards on the door, trouble pressed its nose against the window to fog the glass.

Mira learned fast. She made herself small where she had to and big when she could. She carried twice her weight with a stubborn set to her jaw, and she stood in the doorway sometimes when the wrong kind of eyes followed Fara’s tails.

Fara did the work. She smiled when she could and disappeared when she had to. She stared down the road when no one was watching. Her sleep was strange: shallow, broken, lit at the edges with the faint glimmer of a fifth tail that never quite materialized. Some mornings she woke with her hands clenched so tight the bones ached. Some nights she sat on the back step and whispered his name like a prayer she didn’t believe in.

Skye built routines for them. Eat. Work. Walk the fence line. Count the packs. Check the back trail. Sharpen the knives. She didn’t ask Fara how she felt; she stood where Fara would have fallen, and that was enough. When Skye laughed, it was short and dry and didn’t move her eyes. When she slept, it was with her boots on.

Revoli held together by being useful. She flirted for extra tips when it bought bread for other people at other tables. She slipped out back to cry, came in with her face washed, and made a joke Skye pretended not to hear. She looked at the door more than the rest. When it opened and it wasn’t him, her mouth tightened the way it does when you bite your tongue and keep chewing.

Patrona ran quiet and tight as a bow. She stacked crates, split wood, scrubbed pans until her fingers went red. Helena put a hand on her arm once and said, “You can’t clean your way to safety.” Patrona kept scrubbing. The kiss hadn’t left her. It lived behind her eyes and under her ribs. She replayed it and then punished herself for replaying it. When she looked at the door, she imagined the first thing she would say if he walked through it, then stripped the words down until there was nothing left to say at all.

Cherish came on the fourth day and sat at the corner table like a mountain sitting to rest. She took up space. She always had. Broad shoulders under a leather apron. Horns polished. Shirt half-buttoned because that’s how it fit. The smell of clean sweat and iron trailing her in like a banner.

She didn’t shout. She saw the girls before they saw her. Mira brought her a pitcher and three cups without being asked. Cherish filled one, drank it off, filled it again, and only then waved the girls over.

They came the way you come to a blacksmith’s anvil—respectful of heat.

“What happened?” Cherish asked. No softening. Just the question.

Patrona told it plain. Chapel. Corpses. A necromancer that broke into smoke. Kai drawing the dead away. The run through the trees. The wait. The nothing.

Cherish’s jaw worked. “He’s stubborn,” she said. “Hard to break. Harder to keep down. But stubborn men don’t always make it home. The road doesn’t care how much we love them.”

Fara’s mouth trembled. She held her breath until it stopped.

Cherish put her forearms on the table and leaned in. “You can’t rot here waiting. The town’s turning. Roads are still open. My wagon’s heavy and no one bothers a smith who fixes guard buckles. I can take two with me to Gildenreach. I’m going that way to deliver chain and fittings. You might meet him on the road. Or you might find his trail.”

“Gildenreach?” Skye asked.

“Rich street, pretty stone, bad hearts,” Cherish said. “They like the look of money and collars that shine. It’s where trouble goes when it wants to dress up.”

Patrona nodded once. Decision moved in behind her eyes and took a seat. “We split.” She looked at Skye. “You stay. Fara stays with you.”

Fara opened her mouth. Closed it. She shook her head once, fast. “No. I’m going.”

“You’re not ready to see his body if that’s what we find,” Patrona said. No edge. Just the blade.

Fara flinched like the words had hands.

Skye didn’t look away from Fara when she spoke. “If we have to fight, your head will go somewhere I can’t pull it back from. I’ll keep you here. I’ll keep us ready. If he walks in, he needs faces he knows. Calm ones. That’s us.”

Fara’s ears folded. “I can be calm.”

“Not yet,” Skye said. “Soon. Not yet.”

Revoli’s voice came small. “Then I go with Patrona.”

Patrona didn’t check with anyone else. “You come with me.”

Fara stared at the boards until the grain swam. She nodded. The sound of it sat heavy on the table.

“Time?” Skye asked Cherish.

“Dawn,” Cherish said. “Wagon out back. Wyvern’s temper is best before the heat.”

Helena came and stood with her hands on her hips like a wall that has decided to move. “You’ll take bread and dried meat and you won’t argue about it,” she said. “Mira will pack it. She’ll put the good water with the clear seal so you don’t end up drinking the river by mistake. And you’ll come back if the road doesn’t give you what you want.” She looked at each of them until they dropped their eyes. “All of you.”

They ate together that night, not talking much. Mira tucked charms into the side pockets of the packs—string with three knots, a chipped button, a sliver of horn—little nothings that meant luck if you believed in luck. Fara found one and held it like it weighed more than it did. She didn’t say thank you. She didn’t have to.

At dawn, the wagon stood in the yard with frost on the boards and smoke from its cook-pan climbing thin and straight. The wyvern blinked slow and sullen. Cherish slapped its shoulder like it was a rude apprentice and it huffed but held.

Skye tightened the strap on Revoli’s pack, then did it again. “Don’t be brave when smart will do,” she said.

Revoli nodded.

Skye turned to Patrona. “Bring him back if he wants to be brought. If he doesn’t—” She stopped, swallowed, started again. “Don’t let the road take you too.”

Patrona held Skye’s stare like a hand. “Watch her,” she said, tipping her chin toward Fara.

“I will,” Skye said.

Fara put her arms around Revoli and held on. It was clumsy and too tight. Revoli hugged back just as hard. “Find him,” Fara whispered.

“Or find where he went,” Revoli whispered back. “We’ll bring word either way.”

Fara stepped to Cherish and did something she rarely did: reached for a larger hand. Cherish squeezed once and let go. “I’ll bring back what the road gives me,” she said. “Good or bad.”

They rolled at first light. The wagon wheels cut twin lines in the frost. Skye and Fara stood in the yard until the trees took them. The frost melted where Fara’s breath hit the air.

The road to Gildenreach ran along the tree line and then through it. Cherish took the side tracks when she could, trusting old haulers’ paths that kept her out of sight of patrols and kept the wyvern’s temper low. They made good time. When they stopped, it was for water and to check the harness. When they lingered, it was because Patrona lifted her head like a hound catching scent.

Late on the second day, Cherish reined in without being told. The road bent and the trees opened on a place that had been something else a week ago. Trunks were snapped at angles that didn’t make sense. Limbs hung by threads of bark. The ground wore scars that didn’t look like cart ruts or plow lines—furrows like someone had grabbed the earth and dragged it.

Revoli slid down before the wagon stopped moving. Patrona followed at a walk. No words. Just the taste of iron rising in the mouth when you know.

They spread out. Cherish stayed with the wagon, eyes on the road. Revoli wove between the wreckage, touching nothing, reading everything. Here a print that meant weight. There a smear that meant something had bled and moved anyway. Patrona crouched by a patch of ground where the leaves had been crushed and brushed them aside with three fingers. Her breath came in smaller pieces.

“Here,” Revoli said, voice gone thin.

The batons lay half-hidden under a spray of shattered twigs. Not thrown. Dropped. One end was blackened, the wood scorched, the grip worn smooth by a hand that wouldn’t stop holding.

Patrona picked them up like they were warm. She didn’t cradle them. She didn’t lift them like trophies. She just held them at her sides and stood there long enough for grief to do what it does when it understands something and refuses it at the same time.

Revoli stared at the ground until her eyes blurred. “He fought here,” she said. “But—I don’t see him.”

Patrona turned the batons in her hands and checked the ends the way you check a blade’s edge. “No body,” she said. “No drag marks. Nothing fed on him here.” She looked at the trees. “Smoke-thing, necromancer. It could slip a man without leaving a print.”

Revoli made a sound that was nearly a laugh and wasn’t. “So he’s alive.”

“He was alive after,” Patrona said. “That’s all this tells us.”

They brought the batons back to the wagon. Cherish didn’t ask. She looked at the sticks and then at their faces and clicked her tongue at the wyvern until it settled again.

“Gildenreach?” she asked.

“Gildenreach,” Patrona said.

They rolled on. The road widened and the cobbles began to show in pieces where the dirt had been worn down. Wealth has a smell when it gathers: spice, soap, polished leather, rot under sugar. It rode the wind from ahead.

On the third day they reached the last rise before the city’s outskirts. Gildenreach lay beyond, bright as a shop window. Painted fronts. Hanging signs with gilded edges. People who moved like every eye should be watching them. And beastfolk, always one step behind, collars bright in the sun.

Cherish brought the wagon off the road and into a stand of scrub so they could watch without being counted. “We don’t go through the gate,” she said. “We cut along the orchards and come in at the back lanes. Fewer eyes. More mouths that talk if you pay them to.”

Patrona nodded. She kept one of the batons; Revoli took the other. They felt wrong in new hands and right where they belonged. They tucked them under their cloaks.

“Look for a baker,” Revoli said, surprising herself with how certain it sounded.

Patrona looked at her.

“I don’t know,” Revoli said. “I just— it feels like warm bread and a window.” She shrugged, cheeks pink. “Maybe I’m hungry.”

“Then we’ll start with bakeries,” Patrona said, simple as that.

They rolled down out of the scrub. The wyvern huffed and set its claws careful on the stones. They kept to the edges, where orchards threw shade and the walls hid the worst of the city’s pride. As they went, they watched every face, every collar, every small cruelty done in public like a performance. Cherish spat once. “Rich folk always need something heavy lifted,” she said. “They never lift it themselves.”

They stopped twice more to ask questions without asking them. A fruit seller who had no reason to remember faces, a stable boy who remembered everything because no one believed he could. A woman sweeping her stoop who watched the world and cleaned it with the same hand. The answers were small, but together they grew a shape: a new baker on the main street, opened three days ago, good bread, pretty daughters, the kind of place a town like this pretends it deserves.

Patrona and Revoli sat forward on the bench. Cherish flicked the reins.

They never stopped looking at the road. Not for the gate, not for the guards, not for the men with coin and collars. They looked for one man who sometimes forgot how loud his feet were when he thought he was being quiet.

Somewhere ahead, behind glass and heat and a bell over a door, a family had lost its name to a law. Somewhere between here and there, a set of pikes had pushed someone back. Somewhere in these streets, a pendant lay against a chest and burned cold.

“Not too late,” Revoli said, like she could bully time.

“Not yet,” Patrona said.

The wagon rolled on toward the city that pretended it was kind because its stones were clean. The batons lay across their knees, heavy and right. The three of them watched the path until watching was the only thing that held their bodies together.

Please sign in to leave a comment.