Chapter 0:

Prologue: Sphere

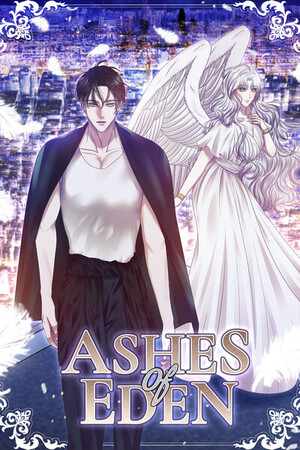

Ashes of Eden: The Serpent’s Return

Author note: Warning, the prologue is on the longer side— so forgive me, it’ll be worth it. (I hope)

Ever wonder what happened to the first fallen angel?

Well, one moment I heard father's voice above me. It was the kind that never had to lift to be obeyed. And the next there was only pressure, like a hand flattening a page. When it ended, I was already on my knees in grass that didn’t bend.

They called it the Garden of Eden. And I was its first and only prisoner. The serpent condemned to this "sanctuary".

If you squint, the lie holds. There are trees with green leaves and slick, silver streams. Moss that never stains. Fruit that ripens to the exact shade of temptation yet still refuses to fall.

But here, the sky is forever night, scattered with stars that look to have been carefully arranged.

You learn faster if you experiment, so I did.

On my first day here, I picked a straight line and walked. I counted my steps until numbers lost meaning, then found myself at a clearing that felt familiar, because it was. Same apple tree. Same stream curving like an obedient signature.

The Garden is a sphere, tucked somewhere in the rift between the heavens and earth. It had the manners of a loop. Every path returns to itself. If you throw a stone, it doesn't arc; it edits. It lands where you expect and then isn’t there when you try to find it again.

I screamed out once, near the start. Habit. The sky did not answer.

What the sky did do though was watch. There’s a feeling of attention here that has nothing to do with sight. The nearest word is weight.

I spent an hour testing the boundaries of that weight like an inmate managing a chain by learning its length. Every time I moved beyond a certain radius, my breath shortened; the air thickened; a hand in my chest pulled me back toward the clearing. Not literal hands, not literal chains. I called it the tether. And the tether never slept.

I am a sinner.

The word they prefer is longer and dressed better, but it dies the same under my teeth. I had time enough to gnaw it smooth. I guess if this prison was supposed to make me sorry, it failed.

I slowly learned the physics of this place, because physics are the only laws that don’t allow negotiation. The stars trace identical arcs nightly; if you stare long enough you can see the seam where the pattern loops. And sound doesn’t travel very far, but it travels forever. I can clap and hear a soft answer hours later, the echo delivered back to me on the same path I used to get rid of it.

My least favorite part is that animals never come. In the first weeks, I listened for wings, for the whine of something small and hungry. Nothing came. Sure, the leaves move when the breeze remembers to do its rounds, but no wind dares to bring company.

In my prison, only angels can enter. They can come and go as they please. I am the exception, of course. They made sure to remind me when they took my wings.

They came, rarely though. Not to speak, but to check that I'm still here, I guess. The barrier admits them like a mirror admits a face; they step through and the sphere briefly tightens, the way a body does around a needle. They walk the perimeter of the clearing and leave without saying a word. Once, one of them left a footprint in the grass, and the Garden healed the mud as if scandalized.

I don’t know how long it was before she arrived. Thousands of colorless years. Maybe even longer. In the Garden, length has very little to push against. You can measure anything if you’re willing to pretend hard enough, so I built a calendar of uncooperative details: how often the fruit on the apple tree warmed against my palm before cooling again; how quickly the echoes of my voice grew bored and stopped answering; the way the stars developed a hairline crack along a seam only I would bother to check. I was wealthy in ticks that amounted to nothing.

But one day, the air thinned the way it does when the sphere makes space for a visitor. I looked up expecting the slow, careful walk of an angel doing a job they wished they didn't have to do.

Instead, I saw her.

White hair, not the ridiculous alabaster you find in frescoes, but the pale of frosty snow. Blue eyes that were undeniably eyes, not lights; when she focused, you could feel the focus. Her robe was simple. Angels can afford simplicity, they’re never mistaken for anything else. She stepped through the boundary like someone negotiating with herself, toes first, heel cautious, as if the Garden might decide to spit her out.

She glanced around, first at the tree, the stream, the sky, and then at me. You can tell a lot about a visitor by where they put their face at the end of the look. She didn’t lower her gaze. She stepped into the clearing, and the Garden let her.

“You’re not on the usual circuit,” I said. That was my attempt at being polite.

“I’m not on any circuit,” she answered. Her voice was clean and unafraid. She took three more steps and stopped well short of the tether’s edge. Either she knew or her feet did. “Are you the serpent they speak about?”

“Depends what they're saying”

Her mouth tilted. Not a smile. Something smaller. “What's your name?”

“Naga.”

“Naga,” she repeated, as if testing the weight of it. “I’m Haneul.”

Only angels never bother with surnames. They don’t need the extra leverage.

She stood, and looked, and kept her hands visible, which was either a kindness or an instinct. I would later learn it was both.

“You shouldn’t come so close to me,” I said.

“That’s what all the other angels tell me,” she said. “Are you as dangerous as they say you are?”

“Depends what they’re saying.”

“They say a lot,” she said, then corrected herself. “Well, mostly just the same thing. That your voice corrupts the purest of us. Does it?”

“Flattering,” I said, dry. “Do you always ask so many questions?”

“I’m told I’m too curious,” she said, which answered my question.

She walked once around the stream, not stepping into it, not touching the water. She looked at the apple fruit, measured it with her eyes and did not reach. “It’s perfect,” she said, and somehow managed to make it not a compliment. “Perfection is a poor substitute for comfort.”

“It’s tidy,” I said.

“Tidy is for shelves,” she said. Then, almost as if she’d remembered to be polite, “Is it disrespectful to ask what you did?”

“Disrespectful to whom?”

“To the story they use to keep you here.”

“I sinned,” I said, and watched her try not to flinch.

“Sinner,” she repeated, as if trying on a coat and finding the shoulders didn’t quite fit. “It’s a big word. People hide behind big words.”

“Angels hide behind big words,” I corrected.

“And you?” She tilted her head. “Do you hide?”

“No. I was caught.”

She took that without argument, which told me she had more sense than her doe-eyed face advertised. “Do you want company?”

“Well, you’re here,” I pointed out.

“That wasn’t the question.” There it was again, the not-smile. “I won’t fill silence for you. I don’t have the inventory. But I can keep you company.”

“You rehearsed that,” I said.

“Not the words,” she said. “The offer, yes.”

The tether in my chest twitched, either in warning or in recognition. I sat beneath the tree to buy myself the seconds to decide which. Haneul stayed where she was until I gestured, then sat as well, leaving three careful spans of grass between us. She placed her hands on her knees.

“The stars aren’t real,” I said, by way of refusing her offer gently, yet accepting it completely.

“I know,” she said.

“Do you?”

“Yes. Real ones wobble.” She tipped her chin. “These are too sure of themselves.”

I hadn’t expected to like her ideas. I hadn’t expected to like her anything. Liking is a doorway; I’ve spent a long time bricking those up from the inside. The Garden took patience and made it a religion, she brought a hammer wrapped in courtesy.

“You're not supposed to talk to me,” I said. “It’s the rule, is it not?”

“It’s a superstition we made into a rule,” she said. “A superstition is only dangerous until you name it.”

“What do you call this one?”

“Caution,” she said. “We say it’s to punish you. Really it’s to make sure you can't trick anyone again.”

“That doesn’t sound like an angel speaking,” I said.

“Angels are allowed to tell the truth,” she said. “We’re just not encouraged to enjoy it.”

She looked again at the apple tree. Her eyes asked permission her hands didn’t. When the permission wasn’t given, she didn’t argue. “I thought it would smell sweeter,” she said.

“It does,” I said, “for the first week. Then it smells like an intention with nowhere to go.”

She laughed, small and surprised, like a sound she wasn’t expecting to make. The Garden noticed. I felt its attention lean in. I didn’t like that.

“I can leave,” she said, hearing the movement in me.

“You came a long way to leave.”

“It isn’t far,” she said.

“Well, you should still leave before they find you talking to me.”

She considered that. “Then I'll be back again.”

“Worst idea I’ve heard today,” I said. “Come back tomorrow and say it again.”

“There isn’t a tomorrow here,” she said.

“There’s always a tomorrow,” I said. “The Garden just refuses to call it by name.”

She looked at me like she was memorizing something for later and stood. She stepped backward through the boundary without giving it the satisfaction of a flinch.

After she was gone, the place felt wrong, and I didn't appreciate the word for what it meant. I walked the loop in long, faultless arcs, waiting through several not-tomorrows.

She returned. Of course she did. Curiosity always overbids policy.

She came more often than the rules would have admitted if the rules were in charge of anything real. Sometimes she asked questions about things that didn’t matter and made them matter by putting them in the air.

Why do you sit there? Because the tether breathes easier when I do. Why do you count the stream’s loops? Because proof and comfort look the same from a distance. Why don’t you touch the fruit? Because I dislike conversations that have only one ending.

Sometimes she brought nothing but attention. Sometimes she brought small stories like seeds she didn’t yet know how to plant. Once, she told me about the outside wind, the uncivilized kind that turns corners without apologizing. I closed my eyes and let the word do the work of air.

“Do you ever wish to be forgiven?” she asked on her sixth visit.

“For which part?” I asked.

“Tempting humans with knowledge.”

“No,” I said, and watched her try to decide whether I was being clever or honest. “What I gave them was the freedom of choice.”

“In what?”

“In whatever they want,” I shrugged, and left it there. The last right I own is to choose how much of my story becomes furniture other people can sit on.

She didn’t sulk. She never sulked. She let the refusal sit next to her and kept breathing like a person who had trained for this kind of weather.

“Haneul,” I said, on a day when the stars creaked louder than they should have, “why do you come?”

“I wanted to see if you were anything like the stories,” she said.

“And?”

“You aren’t,” she said. “You look like a man whose punishment exceeds his crime.”

“That’s one of the stories,” I said.

“It’s the one I believe.”

“You shouldn’t,” I said. “Belief is a gate with quick hands.”

She squinted up at the stars. “Have you given the constellations names?”

“Yes,” I said.

“What are they?”

“Lies,” I said, and she laughed again.

She pushed boundaries carefully, like someone measuring the temperature of a pool, never farther than the tether would tolerate, never close enough to pretend it wasn’t there. Once, she stood with the stream brushing her ankles and watched the water split and reconcile, split and reconcile, until she shivered. “The water doesn’t know how to change,” she said.

“It knows,” I said. “It’s just not allowed.”

She thought about that long enough to make my next several breaths weirdly heavy.

“I don’t think you’re dangerous at all,” she said finally, like someone arguing with a witness.

“That’s exactly why I am,” I said.

“You don’t know that,” she said, which is the kind of sentence that is only ever half about the person you say it to.

She started bringing me stories of the world beneath. Men building castles so tall in hopes of reaching the heavens, crossing seas on nothing but wood and canvas, kings pulling swords from stone.

Haneul grew brave. The visits tightened their spacing, like stitches pulling a wound closed. The Garden noticed and made small protests that only someone sentenced to its habits would feel. I didn't like how much of me began to calibrate to her company.

“I can bring you something,” she said once, eyes bright with the thought of rule-bending. “A book. Or maybe a harp for you to pass the time.”

“Only angels can come and go. That excludes personal belongings.”

“Only certain angels,” she corrected.

“And you’re one of them.”

“Apparently,” she said, and a shadow crossed her mouth at the word I didn’t say: chosen. I almost asked who had chosen her. I didn’t.

On her twelfth visit, she arrived with her robe damp at the hem, hair a little disordered, eyes more steady, somehow. She looked at the apple tree, then at me.

“What?” I asked.

“Nothing,” she said.

The Garden leaned in. The tether flickered like a nerve.

She sat, closer than usual, in a way the tether discouraged. She didn’t fill the silence. I have never been grateful for quiet before. I was then, and I wasn’t fond of the discovery.

“Would you do it again?” She asked finally.

“Which part?”

“Whatever part you think I mean.”

“I would,” I said.

She nodded once, as if something logical had landed where it was supposed to. “I see,” she said, and stood. “I’ll come tomorrow.”

This time she used the word. The Garden heard it like a dare.

After she left, I pressed my palm to the grass where she’d been. It was still warm. The warmth faded the way an apology does when you accept it too quickly. I leaned back against the apple tree and watched the false stars spin their loops. The tether felt lighter and heavier at once, a trick only chains and promises can manage.

I am a sinner. The Garden was built to keep me, specifically, under watch. Haneul knew how to make watching look like something else. I don’t know what word she would have used. Angels own more of them.

If there was a clock here, and I admit it grudgingly, the clock began then. Not because anything in the sky changed. But because I did, against my will. I started counting not loops of water, not my own echoes, not the number of times the apple cooled under my hand. I counted breaths between white hair and silence, between blue eyes and the part of me that preferred quiet.

The Garden pretended not to notice. It always pretends.

But the next time she came, the stream stuttered once, as if it had forgotten for a heartbeat that it wasn't a river. The stars drew their seam tighter and the grass bent easier under her weight. Small things. Small things only matter if they gather.

They gathered.

I sat, and she sat, and we found the exact distance that wouldn’t harm either of us.

And for the first time since my banishment, I had to admit the possibility I disliked most: that the fence they built around me might one day remember how to be a door.

Please sign in to leave a comment.