Chapter 32:

No Place Like Home

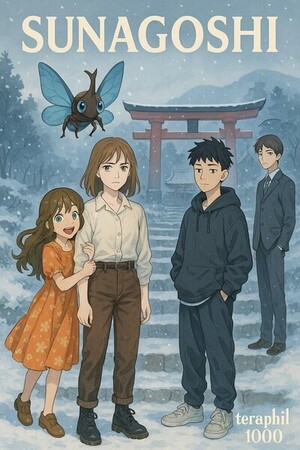

Sunagoshi

The cadent beeping of her cardiac monitor melded with her father's sobs, spotlighting the man's tenderhearted soliloquy with metronimic synchronicity. Inês didn't get to hear him speak Portuguese often, so, in spite of the dire circumstances, she was enjoying the moment.

“És a minha âncora,” he whispered softly. “Não sei o que seria de mim sem ti.”

His anchor, she repeated to herself; no pressure. Although she couldn't exactly say that came as a shock to her; since the passing of her mother, her grandmother and she had pretty much been the only two people outside of his work that her father had kept in regular contact with. Wait, she thought. Her grandmother… Had her father told her what had happened? She would be beside herself once she found out. Inês' next Christmas holiday would hardly be restful—if she made it there.

She was quickly brought from her train of thought back to earth as a piercing pain pulsated in her groin. She couldn't move to feel what it was, but it felt as thought she had been punched or stabbed. Around her, the thick cocoon-like cover still surrounded her up to her clavicles and, on her mouth, the same kind of oxygen mask she had worn in the ambulance was still present, providing a constant supply of warm, humid air. Finally, a poking sensation in her arm led her to believe that she was still receiving some kind of perfusion, although she couldn't see it because of the encasing blanket.

Her dad hovered over Inês for the first time since she had come back to her senses that night. He was the same tall, handsome man that she remembered: dark and serious, with brunet hair and chestnut eyes; a sight for sore eyes. Inês felt immense relief as she saw him. She wasn't sure why, but she immediately wanted to let herself scream and burst into tears. She wanted to speak up and tell him what had happened; that it wasn't her fault; that she hadn't done anything wrong. She wanted him to hold her and tell her that it would all be alright in the end.

Her father placed his hand on her forehead and brushed the hairs out of her eyes.

“Sabes por que é que a tua mãe e eu te pusemos em aulas de música?” her father asked. “Era porque eras tão tímida quando eras pequena… tínhamos tanto medo de que o mundo te devorasse e te cuspisse fora, de que não conseguisses sair viva. Queríamos apenas tornar-te mais forte.”

Mom… She shed a tear for the third time that night.

********

The nausea was overwhelming. The idea of a hot bath had been an oasis of solace for Inês; she had imagined a deep, steaming plunge, in a restful room, with a calming ambiance, but in practice: the lukewarm bath was cold and clinical; the bathroom walls were white, the tub was white, the harsh, glaring light was white, and the smell was the same as the rest of the hospital: antiseptic and monotone. At least, they had started to give her strong analgesics for the pain, so she didn't feel it quite as bad as she had on the first night. The frostbite and ECMO insertion sites felt merely sore and uncomfortable, now.

The bath itself seemed to take an eternity. She was stuck in a room with no stimulation. There was a nurse with her, but Inês wasn't in a state to talk, so she might as well have been put in solitary confinement. The water felt oddly hot for thirty-seven degrees Celsius. Her skin prickled quickly. As another male nurse carried her out of the tub, she began to feel an alien sensation from deep within her: it was as if a kind of sinkhole had caved in inside of her stomach. She felt more nauseous, too; but it was the end of her first full day at the hospital, so she didn't have anything to give up.

Later that day, as the sky streaked into a velvety dusk, the evening nurse came to wrap her hands and feet in sterile compresses. She applied Aloe Vera on her damaged skin, too. For the first time, she put Inês on a glucose IV. It felt different from the saline, but not fulfilling. That was when she finally grasped the emptiness, the hole: she was hungry. She couldn't yet talk, or she would've begged for food.

That night, on her hard mattress and coarse sheets, she dreamed of fresh, crisp bread and rich, sweet chocolate.

********

It was early September in the balmy afternoon. More than two months had passed, and the tourists had deserted Porto, so the São Roque park was largely vacant. Under the cool, late summer sky, Inês strolled casually with her father among the lush greenery. She was carrying the last bites of a bola de Berlim in a café napkin, only eating from time to time whenever the pair stopped to gaze at the pastoral scenes.

They soon paused along a small bridge that overlooked shallow, muddy waters.

“How have your medical appointments been going?” asked her father as he leaned on the quaint, wooden guardrail.

Inês let her shoulders fall.

“Do we really have to speak English?” she sighed.

He looked at her dissatisfied.

“Language…”

“... is power. I know,” she said, resting against the railing and rolling her eyes as her back was turned.

Annoyed, she gulped down the remnants of her pastry in one fell swoop. The cake was sweet and airy, its plush and honeyed sponge like a sugary cloud; the egg custard, golden and dewy, was delectable—if only she hadn't bitten off more than she could chew. As she laboriously attempted to masticate through her mistake, a married couple passed them, each holding one of their little boy's hand. On her back, the wife was carrying a chubby baby, who smiled and reached out to Inês as they traversed the bridge. Her gaze lingered on the happy family as a flock of ducks quacked in the pond below.

“It's been going well,” she finally answered, wiping her mouth with a napkin. “The social worker is nice and the psychologist… Well, I won't have to see the psychologist again, so whatever.”

Her father seemed to hesitate an instant, looking down at his enfolded hands. He turned to face the same way as Inês.

“Can I ask what you told her?” he asked. “The psychologist, I mean.”

Inês stared straight ahead, gazing at the waltzing branches of the oak trees. Their sweet, earthy aroma was soothing to her lagged mind. She turned to her father, the wind pushing her wild, untamed hair over her face.

“You know what I told her,” she said. “It was in the letter I wrote you.”

He tapped his hand on the railing, biting his lip nervously; it seemed he wanted to say something, but couldn't—or didn't know how to. In the end, he walked away. Her arms crossed, Inês followed.

They stopped a little further away, sitting on stone benches, around an ancient-looking stone table. The scene was serene, crowned by an ancient pergola and besieged by thick flora. Every plant in sight was some shade of green, checkered by multicolored flowers; red, of course, but also pink, orange, and yellow. Inês was glad she had chosen to wear her simple canvas shoes that day, because doing all of that walking in her Doc Martens would have surely made her feet bleed. A soft breeze passed through her brown linen trousers, carrying the ambrosial scent of the parterres; abloom. Fall would be here soon, she thought.

“You know, a lot of dads are set on having boys, but I didn't care. My only hope was always for a healthy child,” her father said, wet-eyed. “When you came into this world, you instantly became the most important thing to me… Same thing for your mother.”

He placed his hand on her shoulder. His eyes glimmered.

“I just want to make sure you're doing well,” he continued, the tears streaming down his face. "When I heard what had happened to you… When I saw the video of your rescue…"

"I know," said Inês. "I watched it, too."

“You don't," he cut in. "As an adult… As a parent, it's different. I love you.”

He embraced her and kissed her on the cheek. She hugged him back. Inês couldn't remember the last time she had felt this warm. They stayed fixed in this enduring hold, the wind murmuring around them.

“It's OK if you don't want to talk about it,” he said. “But... you know it was only a dream, right?”

What could she even answer to that? Inês didn't know, so she didn't offer a response. The only thing she could say that would make her father happy in that instant would be a lie; she didn't, indeed know that it had all been a dream. She looked down at the ground; on the stone tiling, a fawn-colored cat was playing predator, chasing a blackbird for supper (or maybe for the love of the game).

Inês got up and began to walk away.

“Come on!” she exclaimed with a quick look back. “It's already past six, and I wanna see the chapel before the park closes.”

“Hey!" her father called to her. "I just realized I haven't seen you reach for your locket at all since your stay in the hospital."

“Oh..." she said as she looked down to the gleaming pendant.

The wind rose softly. She couldn't remember the last time she had clasped her mother's memory.

The São Roque park's chapel was a small, almost square building, attended on its left side by one row of three arches. In front of it, there were short rose bushes and, behind the structure, stood tall, lanky eucalyptus trees. Nearing the end of the day, they had begun releasing their cool odors, akin to perfumes of mint and citrus. Inês felt relaxed in their presence; revived.

There was a group of three children playing and laughing in the low orange sun; chasing each other as the gulls' keening echoed over the tranquil park.

Inês and her father stood silent looking at the small white chapel.

“I didn't know you had put me in music lessons because I was shy,” she said after a beat.

“Pardon me?” her father asked, confused. “Oh, you heard that? Yes, you were a very introverted little girl. Your mom and I wanted to make sur you wouldn't clam up.”

It was a pitiful thought, but it made sense to Inês that her father had only opened up to her as she laid in an hospital bed. He had always been closed-off.

“But why music?” she asked.

“It seemed beneficial,” he said after some consideration. “Like it might make you not just more confident, but also smarter and more cultured.”

Inês analyzed the details of the chapel's architecture carefully. She smiled.

“This all time, I thought you wanted me to learn about our culture,” she said.

Her father looked at her, puzzled.

“Fado, I mean,” she added.

“Well, that's a nice sentiment, but Portugal is in the world's rear view mirror,” he said. “That's why I worked hard for you to speak English; to make you better, to give you a competitive edge.”

Inês gazed into her father's eyes. There was a moment of latency.

The children ran past them, shrieking as they chased each other on their way out, their mothers conversing some distance behind. It was closing time, now.

"It's time to go, I think," said Inês.

Leisurely, they moved in tandem toward the exit. A couple dozen visitors trailed along the veins of the park.

"So, have you decided?" her father asked. "Are you going back to school in two weeks?"

Inês pondered the question, looking up at the scrolling branches with a wistful smile.

"You know, I've had a lot of time to think about it and I think I want to switch schools," she said.

Her father looked at her with concern.

"May I ask why?"

"It's just not my thing. I want to go to a regular school. And I'd also like to focus on the humanities instead of always being forced to take science class after science class."

There was a quietude as they reached the tall, ancient gate of the parc, only disturbed by the anima of the fauna and flora. They passed the wrought iron gate in silence.

"You don't want to go to international school anymore?"

“Não.”

Please sign in to leave a comment.