Chapter 11:

Sparks in the Ring

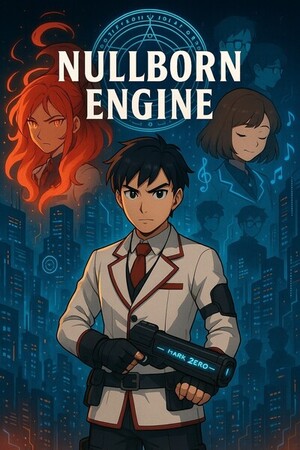

Nullborn Engine

The training yard is a map of small bright things: worn rune tiles that glow faintly underfoot, training dummies scored with past lessons, and the long row of practice stands where upper-years tune their forms like instruments. From above, the campus lights look like a circuit board—braided neon and soft, controlled mana-lamps blinking in polite rhythm. From down here, where your boots meet the stone, the world is only one decision after another.

Kaien meets me at dawn before the first bell. He stands like a problem that refuses to be hurried: long coat loose at the shoulders, wooden blade in hand, patience held in the set of his jaw. “Feet,” he says, once, and the word isn’t a command so much as a diagnosis. “Again.”

We go until the sun is high and indifferent and my muscles forget the difference between pain and instruction. Step, slide, pivot—repeat until the movement is not a choice but something my body knows even when my brain panics. Kaien pinches balance out of my ankles like a potter shaping clay: small nudges, micro-corrections. He forces me to dance the wrong step, then the correct one, until my feet learn how to invent rhythm instead of following someone else’s.

“You can’t be a shadow of someone else’s timing,” he says, tapping my ankle. “Make the song your own.”

That idea sits in me like a stone that wants to be used. If Ayaka writes rhythm like flame—beautiful, precise, inevitable—then I will write mine in steps. Faster. Less predictable. A new chorus.

Renji is already at the workshop when I arrive after Kaien’s hour. He has a thermos, three different bearings, and a grin that looks like it was welded to his face. Kenji arrives five minutes later, with a stack of graphs tucked under one arm like talismans. He thumbs through numbers the way others read names.

“Balance adjustments,” Renji announces, slapping the Mark One case on the bench. “We’re shaving mass from the shroud, moving the center of gravity back, and experimenting with a honeycomb baffle that sings weird when you tap it. Also—we may have found a way to damp the initial impulse with a recoil path that favors the chest wall.”

Kenji’s voice is calm but furious with competence. “By paths, we mean we redirect mechanical impulse on discharge to the frame’s rail and utilize the shock mounting to dissipate lateral torque. The math indicates a reduction in muzzle rise by twenty percent if executed correctly.”

“It’s not going to look sexy on paper,” Renji says, “but it will make you less likely to fall on your face during a duel.”

We spend the morning filing, fitting, and multitasking. Renji sculpts a lighter baffle with a 3D-printed lattice; Kenji fabricates a micro-shock mount with a borrowed barrier spring; I spend more time in the middle—fitting parts, holding tolerances with a focus that’s become practical religion. The bayonet mate slides in and out like a promise: crude, effective, reassuring in its bluntness.

The Mark One is still stubbornly a work-in-progress. Its cylinder indexes clean under my thumb now; the detent clicks satisfyingly. The bayonet brings the pivot point forward, but Renji’s geometry keeps it from turning the whole tool into a blunt instrument. It is not elegant. It is not perfect. It is ours.

“You’ll look like a walking paradox,” Renji says, squinting at the balance. “A gunslinger who wants to be a swordsman.”

“An honest hybrid,” I reply, because it’s less pompous and more what I think.

By midafternoon, the yard is a quilt of duels. Students of all years press in neat rings around the sparring mats like spectators at a small festival. Ayaka’s station is the kind of place that makes a crowd form without a sign. People drift to watch her the way moths drift to lamps—inevitable and a little fearful.

She is waiting when I arrive: hair pulled back in a tight, fire-bright ribbon, eyes like embers – red not just in color but in edge. Her uniform is immaculate in that way that says she is not sloppy in any currency. She looks at me for a heartbeat that reads like a file being inspected.

“You look tired,” she says, which is not an observation and not exactly a warning. “Good. Tired feet make for eager mistakes.”

“Thanks to your training program,” I say, and the banter is the kind you can’t prepare for properly. Ayaka has a way of being both critique and compliment at once—she cuts you down for being sloppy, then lifts you because you improved. It confuses your instincts and clarifies your path at the same time.

We start light. Ayaka’s style is all geometry: wide arcs, denial of approach lanes, the kind of motion that makes you feel obvious. Her flame snaps and hisses like a propellant, each strike precise and economical. I block, then step, then press inside a moment that I will call mine. The bayonet is a weight I never knew I needed; sliding it into position gives me options Ayaka did not intend to hand me.

She does not laugh at the bayonet. She looks at it with the same practical curiosity she gives everything that moves. “It will make you a nuisance in close,” she says. “Good. Be a nuisance.”

She is harder than she was in our first duel. Perhaps victory has not softened her—perhaps it has honed her. She pushes my footwork, denies spaces I had thought I owned. She widens the ring and then tightens it like a hand making a fist. She is the kind of sparring partner who makes you discover what you lack and want it enough to bleed for it.

When we break, my lungs are honest and my shirt is wet. Ayaka’s face is the same, a mask of deliberate neutrality that hides a thousand small evaluations.

“You got in where you could,” she says at last. “You were almost lazy about it halfway through. Don’t let experiments excuse sloppy choices.”

“Noted,” I pant. “If I ever start being lazy I’ll file it off.”

She snorts—an almost-smile. “You’re ridiculous. Don’t make me regret picking you on purpose.”

That last part is not a compliment. It’s a threat wrapped like a dare. And somehow, despite the sting of it, hearing her say it lands in my chest as a thing that might be good. Tsundere or not, Ayaka’s permission—however barbed it is—feels like a new boundary to push.

Hana appears after training with a small kit and the quiet efficiency she’s become known for. We joke that she keeps more bandage than a traveling medic and more sugar in her bag than any respectable engineer should. She sits beside me like she belongs in scenes both small and dangerous. Her fingers move with careful grace; she hums, a tiny, regular sound that fits against the stitches on my palm like a second skin.

This time the hum is just for touch—less overt than anyone could label as magic, and yet the soreness leaves my fingers faster than the cooling should allow. I watch her face, trying to find the moment she looks like she understands her own effect on things.

“You don’t have to hide that,” I say, because in the workshop she used humming like a tool. Here, in the yard, it feels like she’s offering a remedy as well as company.

“What?” she blinks and looks away. “I’m not hiding anything.”

“You call it humming,” I say, smiling. “It works.”

She blushes, a small light under the band. For a second she looks dangerously like she might say something brave, then folds it away. “Good. Rest. You pushed hard. Hydrate.”

The hum is a promise she does not explain. It is enough for now.

Renji and Kenji show up later with a small parade of modifications. Renji clutches printed lattices like talismans and Kenji carries a board of calculations that looks like a modern oracle. They want my feed-back; I want theirs. Together we measure, test, and argue with small, dedicated fury.

“Recoil path,” Kenji explains, sketching in the air. “Think of it like water down a channel. Direct the flow so the gun does not rotate on its axis—push the energy along the barrel’s axis, not across it. Use an internal counter-shield and a spring that dissipates energy gradually.”

Renji nods and then, with theatrical flourish, slides a honeycomb baffle into place. “Also pretty.”

Kenji glares. “Function is prettier.”

We shorten the barrel shroud a fraction, lighten the slide, adjust the baffle pitch. Renji tapes a small counterweight near the grip; it’s a little ugly, but every ugly thing that prevents me from eating stone is a beauty in my book.

“We’ll never be a perfect revolver,” Renji says at one point, wiping metal dust off his glasses. “But we’ll be dangerous in ways people don’t expect.”

That phrase becomes a private hymn for the team.

The small test match is scheduled as a friendly: two first-years who have been friendly enough to make a match interest the class. Eiji Tanaka—fast with a grin and light on his feet—steps up against me. He’s not a top-rank rival, but he’s practiced enough that he will make me uncomfortable. That’s the point.

The rings form. Signboards tally names in neat script. Riku Senzai does not sit at the front this time; he stands on the walkway, hands in his pockets, watching like someone who prefers to observe the eventual collapse rather than the choreography. He looks unimpressed. That’s fine. I’d rather he be unimpressed than indifferent.

We bow. The referee nods. The crowd hushes into the kind of small silence that used to make me want to slip away.

Eiji opens with speed—flashes of motion meant to draw my attention and test my balance. I move the old way at first—feet close, blade high—and it costs me space. He nearly gets a clean opening; Renji coughs behind me in the stands in alarm.

I remember Kaien’s drills: loosen the shoulders, smallest step first, trade the center. My feet start to sing their own map. I don’t think about the bayonet as a weapon as much as a way to be ugly in thoughtful manners. I approach, bait, and then vanish like a cut in cloth.

Eiji overreaches. I slide inside his arc—my shoulder low, feet faster than he expects. The bayonet’s point touches his forearm, just a tap to unbalance. He stumbles. My wooden blade kisses his cheek in a controlled strike that does not injure but does insist.

It is a narrow win. The crowd shouts in surprised approval. Ayaka’s face tightens in a way I can’t read. Riku does not clap. He files the motion into a ledger in his eyes as if preparing an evaluation.

I breathe like a person who nearly forgot how to find air. The bayonet clatters in its mount as I slide my hands up to steady myself. My palm smells faintly of metal shavings and training resin. Hana waits just outside the ring, hands ready. She doesn’t meet my eyes at first; she’s patient like that, never wanting to make the moment about her.

“You were fast,” she says finally, voice a low tide. “You moved like you’d practiced against the wrong rhythm and forced the world to keep up.”

“Kaien said to make my own chorus,” I say. “I think I’m getting there.”

“You are,” she replies. There it is—no fanfare, just a certainty like a bandage laid smooth. She hums a little as she steps forward and wraps a finger around my wrist, testing for tension. “Let me check your grip.”

Her hands are efficient. The hum does what it always does: a small correction in muscle tone, a easing of a clench. When she pulls back, she lingers an extra heartbeat near my fingers. The tiny closeness sends a spark of something warm and ridiculous through me. I suspect Renji notices because he clears his throat loudly.

Ayaka approaches at the edge of the ring. The sparks of a training duel have an energy to them that sometimes turns into something like respect. She looks at me in a way that is not softened and not cruel, just precise. “You moved like you were trying to be less predictable,” she says. “Good. Don’t let unpredictability be sloppy.”

Her words are a new kind of praise. I tuck them into the corner of my chest.

The end of the day leaves us tired and wired. Riku’s presence sits on top of the yard like a cloud that won’t rain on anyone but knows where the lightning would be interesting. He watches, takes notes with a casual hand, and walks away with the sort of stride that indicates his universe gives him small prizes for being efficient.

We close the workshop with new plans and a list of tiny, necessary adjustments. Tomorrow Kenji will test new shock mounts. Renji will try a lighter sight. I will drill my footwork until it reads like a secret language to my legs.

That night on the rooftop, Renji proposes a ridiculous emblem. Kenji draws numbers that could be used to dissolve a city if people let math have their way. Hana hums and folds bandages like she’s composing a lullaby in tape. Ayaka shows up with a thermos for reasons that sound like duty but look suspiciously like curiosity. Her placement near me is still a challenge.

“You will keep moving,” she says, not quite asked, not quite ordered.

“I will,” I answer, and mean it.

The city below us hums and glows and forgets us by design; the academy lights pulse like notes of a song it expects people to dance to. But we are learning to write other measures into the pattern. We move in small, stubborn increments: file, test, pivot, breathe.

Riku’s shadow has lengthened this semester. That is another problem we will face in time. For now I have a revolver that clicks clean, a bayonet that fits, and feet that argue less and listen more. That is not nothing. That is a way forward.

As we leave, Hana slips her hand into mine for the briefest of seconds—so brief Renji misses it, and Kenji writes in his notebook like he has not noticed anything. I carry the touch back inside me like a heat pack.

“Feet, not fear,” I whisper to the city, and my feet reply. Tomorrow will be a new map. Tomorrow, I will keep learning what a chorus of steps can do to a crowd that expects a solo.

Please sign in to leave a comment.