Chapter 31:

The Withering Blue Gentian

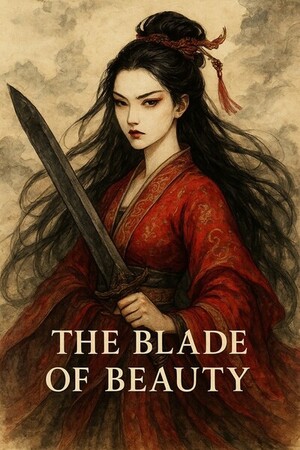

I, a Hermaphrodite, Live by Taking Lives

When Gongsun Yanshu heard the news, he immediately dispatched men to search for it. Of course, planting seeds now would be too late—Wan Ling had only ten days or so remaining before her departure. But if they drove their horses at full speed, uprooting and transporting mature plants back from the borderlands, perhaps they might still make it in time.

In the land of Yichuan there were only four kingdoms. To fetch the lanjin grass from the border between Beiji and Xihan meant cutting across the entire breadth of Yichuan and circling back again. It was a monumental undertaking.

Fortunately, if Gongsun Yanshu possessed one talent beyond his looks, it was wealth. He had coin enough to buy impossible things into being. Three mounted companies thundered forth, scores of fine horses galloping over endless mountain ridges. At last, with only five days left before Wan Ling was to leave the palace, a bundle of lanjin grass was delivered back to the Western Jin manor.

Driven at such speed, the plants had not yet perished, but their slender stems drooped wearily, like exiles torn from their native soil.

That day, Wan Ling was sleeping lightly in her chambers when a pounding knock rattled her door. She opened it to find Shi Wen, Yanshu’s personal page, flushed and panting.

“Madam, you’re awake at last! Quickly, come with me—my lord has prepared a gift for you!”

Wan Ling asked coolly, “What gift?”

“You’ll see when you come! He went through great trouble to find it, only to make you happy.”

Shi Wen meant to create suspense, to shape a moment of surprise. But Wan Ling’s expression remained like carved ice—no joy, no expectation.

He led her deep into the pear orchard, into a clearing suddenly bright and open. That year, the pear blossoms lingered unusually long. Petals white and pink filled the air, half-open and full-bloom, vast and dazzling, engulfing the world in pale radiance.

Beneath one of the trees crouched Gongsun Yanshu himself, laboring in the dirt. At his feet lay several clumps of wilted lanjin grass, their vitality already draining away.

“My lord, Lady Li is here,” Shi Wen announced in a hushed voice, then retreated, leaving the two alone in the vast orchard.

Only then did Wan Ling notice Yanshu’s appearance: he wore a pale violet robe, now stained with blotches of mud, white and black, utterly unlike the polished scion of nobility.

“Wan Ling,” he said with a radiant smile. This smile, for once, was clear and fresh, stripped of the old flamboyance and grease. A few locks of dark hair danced across his brow like a youth in spring. “Come, look at what I’ve prepared for you.”

Without waiting for her reply, he seized her hand, pulling her into a small field of transplanted blue gentian. Spread across the ground in patches, the flowers lay limp, most already shriveled, their once-vivid blossoms wasted.

“I know you love lanjin grass,” he said eagerly. “So I sent men all the way to Beiji to bring them back. They rode day and night, even losing a few horses, but at last they returned. Do you like it?”

The desperate devotion on his face cut into Wan Ling like a blade. She flinched as though struck by lightning and tore her hand violently free.

“Enough!” Her voice burst like steel ground between teeth. “Gongsun Yanshu—enough.”

“What do you mean?” he faltered, a clod of dirt falling from his sleeve. Panic flitted across his face. “Lingling, what is it? What did I do wrong?”

Her answer was swift and merciless. She flicked her blade beneath half a basket of gentian still waiting to be planted, flinging it skyward. One clean stroke split the basket in two, sending the flowers scattering lifelessly across the earth.

Yanshu’s heart bled at the sight. “Wan Ling… why must you do this?”

“Why must I? That is the question you should be asking yourself, Gongsun Yanshu. Why must you?”

“I told you,” he said, staring into her eyes. “Because I like you. I want to be good to you.”

“I am not your Madam Feng, nor your Madam Hou.”

“I’ll send them away. I’ll take no more concubines. You’ll be my only wife. I’ll wed you with the rites of the First Lady.”

“Send them away?” Wan Ling’s laugh was scornful, though her eyes glimmered with dangerous beauty. “And by what right do you discard others? What words did you use when you brought them here? Let me guess. Was it the same you speak now—‘I like you, I want to be good to you’? So they came. You showered them with gifts, perhaps blue gentian or peach blossoms carried across a thousand li. And now? You are tired. So you discard them.”

“No, I never—”

“They are like these flowers.” She crouched, running a hand over the wilting stalks. “On the mountaintops, beneath white clouds, they are a bright patch of blue. There they live five, ten, twenty years, renewing each spring. So long as the root holds, they do not die. But here? Here they will last three days, no more.” She yanked one out by the root and let it fall, uncaring. “I will not be your gentian, nor one of your courtyard ornaments.”

With that, she turned and strode away, leaving him small and desolate in the sea of blossoms.

“Wan Ling!” His voice cracked. “Answer me honestly—do you not feel even a little for me?”

Her only answer was the retreating line of her back.

Blunt as her words were, they carried truth. Wan Ling had laid bare the eternal struggle of new love and old vows, the fickleness of men’s promises, the worth of words so cheap they might coax even pigs to climb trees.

A woman such as Wan Ling—beautiful, powerful in arms, capable of earning her own fortune—had no need to bind herself to a man. Even under the nagging weight of aunties and matchmakers, she would require someone equally strong. And if none such existed, if she truly stood unmatched beneath heaven, then only a man humble enough to live beneath her shadow might do. Gongsun Yanshu, noble-born, destined for titles and thrones, could never be that man.

And his family truly had a throne to inherit.

After that day, Yanshu vanished. Perhaps he was genuinely shaken, tasting for the first time the terror of reasoned words from a woman. For when women argue with logic, few men can endure. Just then, news came of a silver mine discovered in the northern Changlong mountains, and Prince Yongle sent Yanshu to oversee its extraction. Yanshu seized the chance to flee, slipping away without farewell.

Wan Ling required no farewell. She remained quietly in the Western Jin manor, finishing her final days of contract.

On the eve of her departure, she packed her belongings. Her earnings were great—Yanshu had paid not only the agreed sum, but lavished additional gold besides. One chest brimmed with coin. She looked at it, sighed, and left it untouched atop her vanity.

A birdcall sounded suddenly outside. Wan Ling stepped into the courtyard and saw a messenger bird, feathers gleaming with color. At its claw hung a crude silver pendant and a folded note.

She recognized them at once. A sigh escaped her lips as she gazed at the trinket and letter from Yanshu. For a moment she raised her hand to cast them aside—but in the end, she kept them, closing her fingers around the silver.

That pendant was the very token I now held in my hand to trace her memory.

The night sky above was empty, no moon, only a scatter of lonely stars. Wan Ling shouldered her pack and left the manor. She took no excess coin, none of the treasures Yanshu had given, save only that pendant.

As she stepped past the gates of the Western Jin Palace, a cold wind stirred. Gongsun Bai and I followed in her shadow. I whispered the mantra of the Bhasa Art, ready to depart this vision.

Just then, a man emerged from the darkness and strode into her path.

“Sister,” he said.

Wan Ling inclined her head in acknowledgment.

The two vanished together into the night.

“When did Wan Ling get a younger brother?” I muttered. “I’ve never heard of one…”

I wanted to pursue, but it was too late. The spell had already pulled me out. Wind roared in my ears, the scene shifted, and in an instant we were back within the Li Garden chamber.

On the bamboo mat lay the same aged corpse, still and silent, as though it had never moved.

Please sign in to leave a comment.