Chapter 6:

Chapter 6: Exploration of a Grand New World

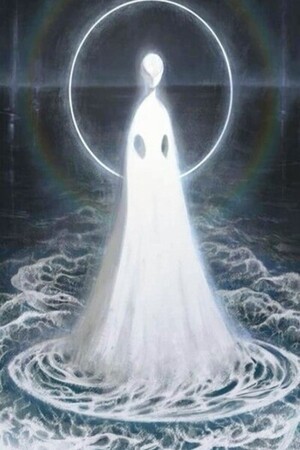

How I Accidentally Became a Deity

The bell did not stop.

Its voice carried down the lane, over the fields, through the mud. Each peal seemed louder than the last, until the air itself felt tight with command.

By the time the priest appeared, the lane was crowded. Men and women who had not been there minutes before now stood shoulder to shoulder, drawn by the sound as if on strings.

Jori clung to Mira's skirt, staring at the priest with wide eyes.

He was not an unkind man. Father Ellard had married them, buried Tarin's parents, and blessed Jori's naming day. He smelled of ink and smoke, and his hands were soft from years of handling scrolls rather than plows.

But this morning, he looked grim.

He stopped at the edge of the field, his dark robes wet at the hem, and his eyes found the ring.

They widened. Just a fraction. Then narrowed again.

"Who prayed?" His voice was quiet, but it carried.

No one spoke.

Ellard's steady gaze passed over them all. "Who prayed?" he repeated again.

Tarin's mouth was dry. He almost stepped forward. He nearly claimed it, the way a man claims a sin, if only to take the punishment cleanly and be done with it. But Jori's small hand in Mira's skirt stopped him.

It wasn't just his field anymore.

Finally, Salla spoke. "We all did, Father. We have been praying for weeks. "This one," she jabbed her stick toward the ring—"heard first."

Ellard approached the circle. He did not cross the line. The flowers pulsed once, slow and patient, and Tarin's stomach turned over.

"...This is not Halven's doing," Ellard said at last.

A murmur rolled through the crowd.

"So whose doing is it?" someone demanded.

"It rained, didn't it?" Salla said, gripping her stick tight. "Call it Halven, call it a wandering spirit, or call it blind luck. I don't care."

"Yes, it rained," Kesh said darkly, "but look at it." He gestured toward the ring of black flowers. "Halven sends grain and golden light, not this—this funeral wreath!"

Another villager, a young woman, spoke up hesitantly. "The rain saved my garden. That has to count for something."

"And my goats drank from the ditch for the first time in days!" another man added.

"Yes, and Chaos Gods will give gifts too," Kesh said, folding his arms. "Sweet wine one day, blood on the doorstep the next."

"It doesn't feel evil," Salla argued, planting her stick. "If it were an Evil God, we'd have woken to rot in the fields, not life!"

Ellard's expression stayed grave. "Chaos is not the same as evil," he said, "but both can be dangerous if not kept to their place."

Mira glanced at Tarin. "So what is it, then? A god that is neither good nor evil?"

Ellard looked at the ring again. "I don't know Mira."

That set off another ripple of murmurs.

Tarin swallowed and stepped forward despite himself. "Whatever it is," he said, "it acknowledged us in our time of need. That should mean something."

Kesh scowled. "Or it means it wants something."

"Most gods do," Salla said dryly. "Halven wants the first sheaf. The Sea-Mother wants a coin at the shore. The Flame-Lord wants his festival fires. Why should this one be different?"

Kesh jabbed a finger toward the flowers. "Because that—" he spat the word "—looks like the work of something that enjoys being feared."

The crowd shifted, restless. No one stepped closer to the ring. Even those defending it kept their distance.

Ellard finally straightened, his decision clear in his face.

"I will not order it burned—not yet, at least. But I will not bless it either. If this is a god, it will show its nature soon enough."

His voice did not shake, but his hands twitched once, barely, and he folded them tightly beneath his sleeves.

His gaze swept the gathered villagers. "None of you are to cross this circle. Do not leave gifts without my say."

"What do you mean, Father?" someone asked.

"If it is good, it will bless you. If it is evil, it will take and take until there is nothing left to pilfer."

"I will send word to the main shrine," Ellard said. "If this is the work of a spirit, they will know how to close it. And if it is worse than that—" he glanced at the flowers, his jaw set "—then we will prepare the rites."

A heavy quiet fell over the group. The words prepare the rites hung there like a storm about to break.

"What rites?" Jori whispered, clutching Mira's skirt.

"The kind that sends a thing back where it came from," Kesh said darkly.

Ellard gave him a sharp look but didn't correct him. "Until we know, no one is to kneel to this circle again. You owe your prayers to Halven, not to nameless things."

He turned toward the lane, motioning for the bell to be stilled. "I will return before dusk," he added over his shoulder, "and I expect to find this field exactly as it is now."

No one spoke after that.

The bell was stilled. The crowd began to thin, talking low among themselves, glancing back at the ring as if it might move when they weren't looking.

Tarin stayed where he was until the last of them were gone. The lane was quiet again, the only sound the drip of rain from the eaves and Jori's distant laughter as Mira led him back toward the house.

He looked at the ring, at the wet bread still sitting untouched, and felt the weight of Ellard's words pressing down on him like a millstone.

If this were a trap, he should burn it.

If this were a blessing, he should guard it.

He thought of Mira, coughing over the cooking fire last week when the smoke got in her throat. He thought of Jori asking if there would be bread the next day. He thought of the neighbors who had nearly come to blows over water from the well.

And then he thought of the night before, the petal drifting down from nowhere, the clouds opening, the way the rain had come down.

Halven hadn't answered then.

Slowly, Tarin stepped closer to the ring until he could smell the strange, sharp sweetness of the flowers.

"I don't know who you are," he said softly. "But you fed us when no one else would. So I'll keep this field safe. At least until you show your hand."

The flowers pulsed—once, twice—slow as a heartbeat.

Tarin waited until the feeling passed, then straightened and brushed the mud from his knees.

He didn't feel lighter, but he felt more sure of himself.

---

Isaac lingered in the quiet long after the last of the villagers had gone, still pressed thin in the shelter of the flowers.

The two presences that had nearly burned through him were gone now — not entirely gone, but distant, their weight on the world lifted like a storm passing over the horizon.

He could feel where they had gone, faintly. Halven's warmth was trailing westward, toward the shrines and granaries where his name was strongest.

The other presence had scattered, thin, and diffuse.

Only then did Isaac dare to unfurl again.

'Guess the coast is clear,' he muttered, though he still felt like someone hiding under the floorboards after a raid.

The silence that followed was mute, and in that hush, Isaac felt them.

The threads.

He floated higher, slowly, letting the lines of prayer come into focus one by one. Most had quieted now, but still faintly glowing.

Isaac floated above the village for a long while after the crowd had dispersed, watching the thin lines of prayer go quiet one by one.

The threads didn't vanish—they never really did—but they dimmed.

All except one.

Tarin's thread burned steadily and brightly.

When he brushed against it, the farmer's resolve came rushing in: Mira's tired eyes, Jori's laugh, the thought of an empty yard where goats once bleated.

Tarin had weighed Ellard's warning, weighed the fear in his neighbors' voices—and still chosen to keep the field safe.

The weight of it made Isaac's formless chest ache.

It was like standing in a room with one other person and realizing they had just made up their mind about something that would change both of you forever.

Isaac recoiled from the weight of it, startled at how heavy one man's decision could feel.

'Whoa. Whoa. That's—' he broke off, trying to catch a breath he didn't have. 'That's… not what I signed up for.'

Except… what had he signed up for?

He floated higher until the fields blurred into a patchwork of gold and green. The black ring shrank to a single pinprick of darkness in the middle of all that life.

Tarin's faith, if you could call it that, still tugged at him, a constant presence, no louder than before but impossible to ignore.

It wasn't like having a follower in a video game. There was no meter, no number he could look at. It was just there, humming in the back of his mind.

And he couldn't shake the feeling that it mattered.

If he failed, it wouldn't just be a loss of XP or a "bad end." It would be Tarin's boy going hungry again. Mira's cough worsening when winter came.

For the first time since arriving here, Isaac felt the sharp edge of responsibility.

'God,' he muttered, then winced. 'Okay, not the best choice of words.'

He drifted away from the village, letting the thread stretch behind him like a tether. He needed space, not just physical, but mental, to think.

What was he, really?

A god? That word still felt wrong in his mental mouth. Gods were supposed to be grand, omniscient, radiating power. He was just… him. A guy who used to stay up too late reading web novels and drinking bad coffee.

He still remembered the glow of his computer screen, the half-empty mugs, the moment right before the pain hit.

And the single line he'd typed.

What if there was another god?

'Yeah,' Isaac said softly, staring down at the world. 'What if.'

He drifted for what felt like hours, tracing the lines of rivers, watching clouds cast slow-moving shadows over the hills. The world below was beautiful—painfully so—and alive in a way Earth never had been. He could sense it now, in every stone and root and crawling thing.

And for the first time, he let himself wonder:

Where was he?

Not just which field, which village—but which world.

When he'd first woken, he'd been too disoriented to ask the question. Then, too panicked, too busy running from the gods' attention, too consumed with figuring out what he was.

But now, with Tarin's choice anchoring him like a stake driven into the earth, he found he wanted to know. Needed to know.

Because if he didn't, he was just flailing in the dark.

He turned his attention outward to the world itself.

The thread to Tarin still hummed in the back of his awareness, an anchor tugging gently at him. But Isaac pushed past it, his focus sweeping eastward.

It felt like leaning over a balcony rail, stretching farther and farther to see what lay below.

He felt the edges of the forest, the distant outline of a river delta, the warm swath of grasslands where herds of something horned and four-legged grazed in peace.

The land unfolded beneath him in wide, rolling hills. He passed over creeks swollen with last night's rain, saw clouds catching on the ridges like torn cloth, and a great many things.

Everywhere he went, prayers shimmered faintly, so many of them that it made his head spin if he focused too hard.

They were small and ordinary: thanks for safe births, pleas for fair weather, curses muttered under breath.

He pushed further.

Soon, the fields gave way to rougher country. A road unspooled beneath him, hard-packed earth with ruts worn deep by cart wheels.

A line of travelers moved along it: merchants with laden mules, a pair of soldiers in patchy leather armor, a peddler leading a squeaky-wheeled cart.

Isaac hovered above them, fascinated.

They couldn't see him—of course, they couldn't—but the thought of being so close to actual people again sent something tight through his chest.

He drifted lower, just enough to catch fragments of sound: the creak of the wagon, the jingle of harness bells, the soldiers arguing softly about whether the next inn had decent ale.

And under it all, faint prayers.

One of the soldiers was silently thanking Halven for keeping the roads clear of bandits. The peddler was muttering to a god Isaac didn't know, asking for good sales.

Isaac found himself smiling despite everything.

'This is insane,' he said. 'I'm eavesdropping on people's thoughts like some kind of psychic.'

He turned east, away from the road, and traveled until the trees thinned and the land rose into high, open country.

From here, he could see farther than before: a sweep of hills, a silver river winding toward a distant mountain range. Smoke rose from somewhere far away—a village, maybe a fort.

He floated there for a long moment, drinking it in.

He had never been anywhere like this.

No cities. No smog. No cars. Just a world so big it felt like it might swallow him whole.

For the first time since arriving, he felt small in a way that wasn't entirely unpleasant.

He drifted further, faster now, covering miles in heartbeats. He passed over lonely farmsteads, over wild grasslands where herds thundered at the edge of his awareness, over an abandoned watchtower that leaned drunkenly to one side.

At one point, he spotted another caravan with banners fluttering and guards on horseback. The prayers there were bright and varied: merchants asking for profit, guards praying for a quiet road, one kid in the back of a wagon asking the gods for pie at the next stop.

Isaac almost laughed.

The world was big.

Alive.

Terrifying.

And he was right in the middle of it.

Isaac rose higher, the curve of the world bending at the edges of his vision. Roads carved invisible lines across the land, rivers gleamed like silver threads, and mountains split the horizon like jagged scars.

Somewhere beyond all that, other gods were waiting.

He didn't know if they were patient.

Or merciful.

But they were there.

He hovered at the edge of the sky, the tether to Tarin still glowing behind him.

If he didn't understand this world—its prayers, its people, its rules—he'd lose it.

Lose Tarin.

Lose himself.

He turned east.

The world had prayers for everything: harvest, storm, mercy, wine. But none for gods who hadn't picked a name yet.

And in a thought, he was gone—a spark racing the horizon.

Please sign in to leave a comment.