Chapter 25:

What remains

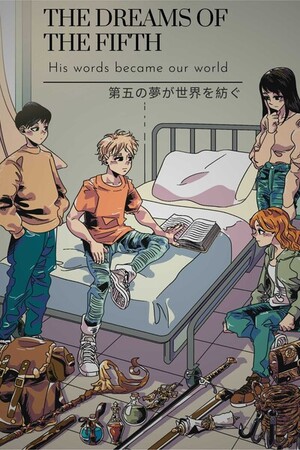

The Dreams Of The Fifth - His words Became our world

They gave it a night to settle. Supplies were packed into sacks, blades sharpened, cloaks mended against the rain. The city pressed against the shutters with its usual noise, but none of them slept easily. By morning, when the lamps were still burning low and the streets outside were slick with runoff, Darius led them out by a back road that avoided the markets altogether. They didn’t look back. The plan was set, and if the Unwoven hunted villages, then the next faces they wore would be villagers’.

The road away from Lerenic felt narrower than it had when they’d first come into the city. It sloped and curled between hedgerows and low stone walls until the houses thinned and the smell of smoke changed from city grease to woodsmoke and damp earth. Darius walked with his head down like a man who preferred listening to speaking; the others followed in a ragged line, cloaks pulled up, hoods low. The market noise dropped behind them and the world grew quieter in a way that felt dangerous rather than peaceful, as if the open sky could hide as much as it revealed.

The village showed itself slow — a scatter of low cottages gathered around a well, a chapel-half-ruined with its bell rope knotted and frayed, a longhouse with a thatched roof sagging in places. Fields bowed with winter stubble. A lane of worn flagstones led to a green where a few children ran with knotted rags pretending to be flags. No market, no stall-loud bargains, only the ordinary sounds of someone scraping a pot, a dog barking, the clack of a cartwheel easing by. It was the kind of place an army could walk past without noticing, and the kind of place a cunning hand could strip as easy as fruit from a branch.

Darius slowed at the green and ducked his head to speak to a man sitting on an upturned crate. The man’s hair was white as bone and his hands were webbed with work; his eyes lifted and registered Darius like a man who recognized an old face. There was no fanfare, no words of introduction; Darius simply moved on, cast the others a look that said this was the place, and let them file behind him.

They were not given a home so much as shown a hollow — a small cottage at the edge of the hamlet whose owner had gone to the city with a promise to return and never did. The house smelled of dust and dry herbs and the faint animal-sour of sheets left unused. There was a bed, a cracked wooden table, a hearth whose stones had blackened long before. It was functional in the way an empty thing could be: a shelter with room to breathe, a place to pretend to be less than they were.

For the first day they moved like apprentices to a craft they hadn’t learned. They chopped wood with the kind of clumsy rhythm that comes from armies of practice, from years of being hungry for a rhythm other than rage. They fetched water and stacked it by the hearth, their hands surprised by ordinary work: the small soreness of a shoulder used for carrying rather than clenching. Ren sat with the gauntlet hidden under his sleeve and watched hands that didn’t belong to war — a woman tending soft lamb, a boy sweeping straw — and learned how to make the motions look natural. Miyako folded cloth with an economy of motion that suggested she’d once had to make strangers trust her by action alone; Hibiki hauled stones until his arms sang with fatigue and then hauled more.

They kept to themselves because Darius had said so, and because it was easier. The villagers watched from thresholds and doorways — wary not of them personally, but of the world that had come knocking. Eyes flitted to Hibiki’s shoulders, to the gauntlet peeking beneath Ren’s sleeve, to the bandaged ribs under Darius’s coat. But the elder would move through the green with a staff and a manner that called the village together like wind calls leaves. When he passed Darius paused and then stepped back so the elder could nod once, a motion small enough to miss for anyone not looking. That single nod carried more than words — an old recommendation in a community that traded reputation like coin.

Trust was a slow thing, and yet the village found a way to hand it to strangers who could lift a roof when the wind came. They helped where it was needed: a woman who owned half the green showed them how to gut a flounder without dulling the flesh; a boy with a chipped knee taught Hibiki the best way to set a trap for rabbits. Conversation between them was simple, uncomplicated European things — a nod, a short smile, small gifts of hard cheese passed over the table. The greatest kindness offered was a frown that meant "work for it" rather than "get out." Darius liked that kind of generosity; it was earned rather than given and therefore more honest.

Day dwindled into a long wash of yellow dusk. The children were called in. A dog nosed through the thatch for left-over peels, and smoke rolled soft from hedgerow chimneys. Ren watched Miyako in the doorway as she distributed the last of the dry roots; she moved like someone who knew that nothing could be taken on trust. Her eyes counted the exits to the green as if mapping escape routes, then returned to the old rhythms of baking and mending. It didn't look like much and yet there was a satisfaction in it — a sense of being less hunted for a few hours. It was a small, dangerous comfort.

They ate with the villagers that night, not in silence but without much conversation, plates passed, soup ladled out, flamelight throwing their faces into half-truths. The elder sat near them, a large man with knuckled hands and the patience of someone who had seen many winters. He watched them with the detached gratitude of a farmer watching rain: measure, note, move on. He did not ask who they were beyond what work they could do; he needed protectors more precisely than reasons. Darius, who had once slept on floors that were never his, drank slowly and kept his council to the look he gave the elder later when they thought no one watched.

There was an undercurrent; the village’s quiet was threaded with a fear that refused to hide. Someone had knocked on a farmstead at dusk, a family taken without a sound — tale told with lowered voices and the same sullen anger passed from mother to son. The elder’s mouth tightened when the story came around and then he made a motion to change the subject, like a man dragging a sick animal back into a stall. They could all see what was left unsaid: that the world beyond these lanes had teeth for the small and hungry.

Miyako walked to the inn that evening under the pretense of checking if there were any new faces in town. The inn was small and honest — a low-beamed room with a hearth and a counter, tankards on the shelf, and inebriates sleeping off day’s work on benches. She came back with a list of two men who had been asking questions recently and a shorthand phrase in the corner of a ledger that suggested the city was trading in people. Her face was closed; she reported without flourish. Hibiki learned a way to carry a fur so it looked like he’d hunted it. Ren apprenticed in mending the hems of shirts so his hands looked like a villager’s, not a soldier’s.

The calm arrived like a tide. For a few days the village wore them like a cloak. They rose before light and returned after dusk; hands worked the chores of neighborliness, and with each scrape of the knife or bucket carried to the well their mask settled more comfortably. Importantly, the village’s doors, which had been tightly latched at the beginning, loosened. A woman repaired a hole in their thatch and left a small pot of preserved plums on their windowsill without comment. A child crept into the cottage and left a painted pebble on the table, eyes bright and unafraid. The elder, when he spoke, did not need to say much: in the small motion of him offering a pipe and a seat, the village said, without the brittle edges of the city, that they would be watched, but perhaps by friendlier eyes.

They slept with a careful kind of slumber, the sort that stays light and listens. It is one thing to pretend to be a farmer by day and another to sleep in a bed and let the day tell you it is safe. Each night, before drowsing, Ren would take the gauntlet off and leave it under the bed, as if the act of not wearing it would somehow make him less dangerous. Hibiki sat awake sometimes at the edge of the green and stared into darkness until his vision was full of movement that wasn’t there.

The first attack came not as a roar but as a shadow pulled taut and then broken. The moon was a sliver; the wind that night smelled sharp, a clean edge that should have meant frost by morning. The sound that woke them was a low rustling, deliberate and soft — the kind that is practiced, not panicked. It came from the lane, then from the hedgerows, a succession of feet made to be silent. They were not alone.

They saw them first as color, not as shape: robes that caught and did not catch the torchlight, different hues indicating rank: dull grey for the scouts, something darker and heavier for the foot-men, and a strange, whispering white for those whose edges seemed to swallow the light. The white were not the bright, holy white of a chapel; it was the color of bone washed in bleach and simmered in candle wax, and it moved like breath does in cold weather, slow and inevitable. Where they passed, dogs fell silent. Where their feet fell, earth seemed to know to give way.

There was no shout, only a rustle of cloth and the soft mechanical clack of tools. The cultists moved with a choreography that was terrifying in its calm — a pack that had studied the steps of humility and used them for hunger. They came in medium ranks, enough to force the villagers to run or fall but not enough to sack the hamlet in an hour. Their aim was surgical; they were a harvest, not a war.

Hibiki was the first to move, as if the scent of unfairness had been a flare to the rawness in him. He spilled from the doorway with the morning star catching like an omen of metal, and for a moment fear and violence became the same thing. The first scout did not so much see him as be startled by weight, and his chain found flesh. Hibiki's swing carried a note that the village had not been given; it had sound to it, a low bell that made the earth answer. For the briefest span his control went slack and the hum from his weapon rose like thunder from a buried drum. Villagers ducked, blue faces turning to watch if the strangers they had trusted were monsters or saviors.

Miyako moved like the space between strikes. She closed on an assailant with a knife that was nothing more than a whisper. Her motion was clean and practical, meant to end movement not to admire it. Darius pushed through the crowd with the slow force of someone who knew how to make a body occupy a space and keep it. Ren, gauntlet flashing in the uncertain torchlight, found himself braced not by bravado but by the simple rule Darius had hammered into them: make your weight the first thing they meet. He drove his blade down with the weight of a hand he could trust.

There were moments in the fight that looked like tableau — a child clutching a broom like a weapon, a woman sliding down a wall and then throwing a pot at a cultist’s head. There were moments that were uglier; a footman in grey came into a house and took what he wanted and left a shadow on the floor that did not belong to the villagers. The white-robed folk moved to the center with their slow, ceremonial calm, and around them the others tried to carve out a fleeing path. The village was small but the resolve in village hearts can be as thick as timber, and tonight the villagers fought as people defending a hearth rather than as soldiers.

For a while it was chaos, for a while it was method. Hibiki’s hum climbed so loud that stone seemed to answer, and for a sick second Ren feared that his friend would not stop and that he would have to stop him. But Miyako’s hand was on Hibiki’s shoulder, a grip that was not friendly but firm, and she turned his weight into a net rather than a hammer. Darius’ club met the soft parts of the attackers — the knee, the wrist, the jaw — and his blows were slow, precise, cruelly efficient. They were a thing of a different season of fighting: deliberate and meant to preserve what needed preserving. It was ugly and clean at the same time.

They pushed. They drove a line that the cultists could not easily step across. The white-robed woman at the head of the force struck with a calm that was like frost. Her robe was different, edged with a thin red thread that shone in the torchlight; her hands were steady, and an angry, animal sound broke from her throat once, not human in the way it split the night. She moved as if she were trimming something unnecessary. For every man the villagers felled, two more crept forward. For every space they cleared, another white-sleeved arm would weave in. The village became a room of people and they were stacked against the night.

They nearly lost a small house; the thatch caught fire, and for a choking moment the world was light and heat and sharp fear. The children wailed. The elder’s staff cracked under the weight of his swing and then he fell back, breathing hard, but still watching. In one instant a flock of villagers made a human chain: one pulled a child through a low window, another pushed a table against a door. It was crude, panicked, and it remembered the life they had before the world learned to take their people.

When the edge of dawn glinted on the thatch, when the white robes were finally pushed back and the last of their forms slipped into hedgerows and under hedges, the village breathed a long, frightened breath. The ground was stamped, the hedges torn, the air full of the sulphur-smell of old torch oil. Injuries were tended with rough hands; someone brewed an infusion of bitter roots and passed cups to those who could not sleep. The villagers clustered and looked at the strangers with new eyes. Where suspicion had sat before, something closer to gratitude now took root. They had been saved, battered and ragged though it was, by the hands they had let in.

The elder came to the cottage and sat at their table. He looked at the gauntlet and at Hibiki’s blood-streaked forearm and then at Darius. The look he gave was not of a man surprised, but of a man recalculating risk in the ledger of a life. He spoke then, his voice low and steady, folding his words like a man mending cloth for sale: there had been a place on the edge of the Quarter where men in white came and left with the village’s missing — a ruined granary and cellars beneath it, a passage sealed in the stone. He pressed a small scrap of weathered paper into Darius’s hand — a hand drawn map, a point marked roughly at the granary.

Hope was a thin thing but it had weight. They had come as masks and left that night as muscle: protectors in the eyes of people who would now point them toward what they needed most. The elder’s nod was small, but it beat any shout. The villagers would speak. They would send word to a neighbor who’d seen a man come in the wrong time. For now, the village would stand between them and the city’s teeth, and in return the group had given it bones to stand on.

They slept badly that dawn, every nerve still ringing from the night’s clang. Wounds stung, but nothing a bit of wine and stout hands could not bind. Ren picked at a frayed strap on the gauntlet and thought about the map folded in Darius’s pocket. Alice felt a thread closer, a knot about to be pulled. Hibiki sat outside and watched the children as they ran in the pale wash of morning. Miyako washed her knives with a slow, careful motion and then wrapped them in oilcloth, hands steady again.

Outside, the hedgerow made a small rustle as sparrows came out and took up their small wars over seed, and the village’s ordinary life went on. The elder blessed them with the kind of quiet acceptance that was not praise but duty. It was not much in the ledger of the world, but it was enough. For the moment, their disguise had worked, and the plan that had seemed a gamble at market now seem a lot more.

Please sign in to leave a comment.