Chapter 5:

The Painted Face of the Fox

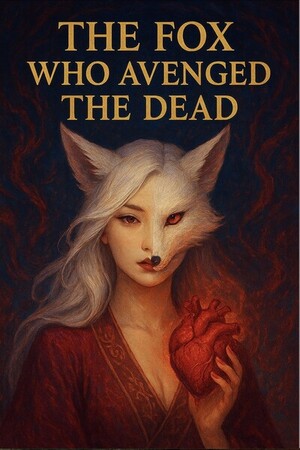

The Fox Who Avenged the Dead

After a full month of strange treatments, the effects had finally shown.

You must understand: we foxes of Xuhe Mountain are all “skinless,” but not from the moment of birth. According to the old laws, every fox born inside the mountain, upon reaching three months of age, must be sent into the Hall of Penalties, where the austere Lord of Caution personally peels away our fox-skins. Only by losing that fur and hide can we keep our lives.

Once stripped, we have nothing left to cover ourselves but raw, bleeding flesh. I have lived five hundred years without skin or face, so accustomed to it that it became part of me. But now, as the makeshift sheet was finally torn away, I stared in disbelief at the smooth, glistening new skin covering my body. The sensation was strange, almost unbearable, as though I had been forced into someone else’s form.

Only one thing was missing: I still had no face. No eyes, no nose, no mouth — a blank mask that would terrify anyone. Seeing this, Little Green decided to “do good all the way to the end.”

“Even if you don’t look very pleasing to the eye,” he said with a mix of pity and scolding, “you’re still a female fox after all. Appearance matters. I may be only a mountain herbalist, but I know a little of painting. Cough… shall I paint you a face?”

I hesitated for a long moment, then shook my head seriously.

“No need. I’m satisfied as I am. Having skin at all is already a heaven-sent blessing. If you paint me a face, you might attract the gaze of the Heavenly Emperor and the Celestial Empress themselves. Who knows what calamity might follow?”

Little Green staggered back as if struck, nearly losing his footing. His finger trembled as he pointed at me.

“I… I’m finally willing to be a good man for once, and you actually refuse?”

I nodded again, honest and calm.

He looked crushed. Truly, I did not realize how deeply my refusal wounded him. All I knew was that from that day on, he turned cold and distant. He still went out to gather herbs, still ground powders and mixed pastes, still painted endlessly on his scrolls, but when I tried to follow him like before, he looked past me as though I were air.

Eventually, Little Green fell ill. He lay on his bed and refused to take medicine. People say a healer cannot heal himself; I watched him grow thinner by the day, even the green of his robe losing its life. In desperation I rummaged through his cabinets, boiled every herb I could find into a dark, pungent soup after several hours of clumsy work, and brought the steaming bowl to him.

He turned his head away and said hoarsely, “It’s a sickness of the heart. Ordinary medicine can’t cure it.”

I almost slapped him unconscious just to pour the brew down his throat, but he looked so fragile I feared one slap might send him straight to the Yellow Springs.

Thinking hard, I realized his “sickness” had begun the day I rejected his offer. With a long sigh, I said softly, “Drink this medicine, and I’ll agree to your request.”

Little Green bolted upright as though reborn. In an instant he was cured.

I still remember that day clearly. The sky was clear and bright, a rare warmth in this rugged land. Little Green donned yet another dark-green robe and even tied his hair with a ribbon, arranging it like an immortal sage.

The brush he took up to paint my face was unlike anything I had ever seen — a jade pen carved with a single phoenix ready to take flight. Dipping it into colors, he began to stroke my blank skin. I heard only the soft “swish swish” of the brush, felt an itch as if something delicate and alive was blooming across my face.

After a while, he set the pen down and wrapped my face tightly with a sheet once more. Through the fabric, I heard a voice like a breeze from a distant mountain:

“It’s time for you to come back.”

And then, for no reason, an old story came back to me.

It was the story of a poor scholar and a rich man’s daughter. They loved each other but were torn apart by class and family. The scholar fell gravely ill and emerged changed, colder, stranger. One day on the mountain he found a piece of fragrant wood, clearly no ordinary thing, and brought it home. He spent months carving it into the likeness of his beloved, pouring all his longing into that block.

Years passed. One evening, the scholar opened his door to find the very lady he had longed for standing there, saying she had run away for him. Overjoyed, he took her in; the wooden figure was gone, but who cared? Now the real one was here. They lived together in bliss.

Until, one day, a wandering monk passed by. The scholar gave him a bun out of kindness. In return, the monk handed him a talisman, saying it could ward off evil. The scholar stuck it on his door without thought.

That night, after their usual intimacy, the woman in his arms turned into a cold wooden effigy. Horrified, he fled, then sought out the lady’s family. She was married, with children. The truth was plain: the woman he had lived with was the wooden substitute he himself had carved, animated by longing.

When he finally returned home, there was no one there — only a pile of splintered wood. The wooden woman had realized the truth when she saw the talisman and, in despair, shattered herself. She had been a rare “fragrant blossom wood” spirit, made human by his affection. Without him, she had no reason to live.

The monk appeared again, marveling at the sight: dead matter cannot become immortal, yet these broken pieces not only had awareness but had conceived a child. He even asked for a piece to make a temple’s wooden fish. That night, the scholar killed himself.

A ridiculous story, yes, but one that had etched itself into my mind after countless idle readings of folk tales in Xuhe Mountain. I had drawn two lessons:

First, when a man paints a woman’s face, that woman is almost certainly the one he loves.

Second, backup loves are dangerous; they drive everyone mad.

I didn’t know why this story rose in me as Little Green painted, but as his strokes multiplied my doubts grew heavier. His hands trembled, his breath quickened. Whose face was he painting? Was it truly mine, or some woman from his past?

Suddenly I did not want the answer anymore.

I sat still, the sheet over my face, feeling the faint warmth of his fingers through the cloth. The brush stopped moving, but my heart beat faster and faster. Outside, a winter wind brushed against the walls of the hut, and somewhere deep inside I sensed the old, sealed power of Xuhe Mountain shifting, like a sleeping beast about to open its eyes.

Please sign in to leave a comment.