Chapter 12:

La Paz

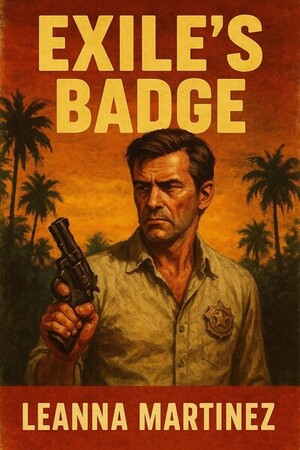

Exile's Badge

Sam left San Francisco the way a man leaves a crime scene, quiet, no explanations, no backward glance. A single duffel slung over his shoulder, revolver buried beneath a change of clothes. He didn’t write a note, didn’t leave a forwarding address. There was no one left to read it.

The road south was a blur of bus stations and neon diners. Fresno at dawn, the terminal air thick with stale coffee and sweat. Bakersfield under a high sun, the desert heat pressing down as he bought another ticket with wrinkled bills. He slept in jerks and starts, forehead against rattling windows, dreams bleeding into the drone of the tires.

By the time he reached the border at Tijuana, the duffel felt like it weighed a hundred pounds. The crossing was nothing more than a shuffle through lines, a man with a badge waving him past without a second look. Nobody asked questions, and Sam gave no answers. South of the border, the road stretched endless, desert on both sides, the air shimmering above cracked pavement.

He didn’t stop until La Paz.

The town clung to the edge of the Sea of Cortez, where the water shone too blue to be real and the heat pressed down like a hand. Fishing boats bobbed in the harbor, their paint peeling, their nets smelling of salt and rot. Tourists drifted along the malecón in the evenings, sunburned and happy with cheap beer and ceviche. But just a street inland, the town shifted—dusty plazas, shuttered shops, men who watched everything with quiet, practiced eyes.

Sam found a room above a bar, cheap because of the noise. The air smelled of tequila and fried fish, the floorboards thin enough that he could hear the jukebox below until dawn. The room had a bed, a table, and a fan that worked only when it felt like it. It was enough.

He paid in cash, always in cash. His Spanish was rough, broken phrases picked up from years on the job, but here it didn’t matter. Money spoke clearer than grammar. He carried crates for the fishermen, scrubbed decks slick with brine, and stood night watch at a boatyard where stray dogs barked at shadows. Nobody asked who he was before. Nobody cared.

In the mornings he sat on the seawall, drinking bitter coffee from a tin cup, watching pelicans dive headfirst into the surf. Sometimes he thought about Maggie and Emily. Sometimes he thought about Caruso. More often, he tried not to think at all. The tide came in, the tide went out, and each day blurred into the next until time itself felt like a rumor.

For a while, the life almost suited him. The anonymity. The rhythm of the sea. The way the town didn’t expect him to be anything more than another gringo drifting through. He grew a beard, stopped wearing a watch, let the sun roughen his skin. The revolver stayed buried in the duffel. Some nights he drank beer until sleep finally came, and other nights he lay awake staring at the ceiling fan, listening to the ocean grind against the shore.

It wasn’t redemption. It wasn’t even peace. But it was distance. And distance was enough to keep breathing.

* * *

The days settled into a rhythm so dull it almost felt like safety. Sam let the beard grow in, rough and uneven, until even he barely recognized the face in the mirror. He stopped carrying the revolver everywhere. Most days it stayed in the duffel, wrapped in an old shirt. The weight of it no longer comforted him; it only reminded him of choices not made, of a trigger never pulled.

He found work where he could. Mornings on the docks hauling crates of fish, the salt water soaking into his clothes until the smell followed him everywhere. Afternoons spent patching nets with men who barely spoke to him, their leathery hands working quick while the sea breeze numbed his thoughts. Nights as a watchman, sitting under a flickering bulb with stray dogs keeping him company, listening to the creak of boats shifting in their moorings.

The food was simple—fish stew heavy with spice, bread baked too hard, tequila poured strong enough to make the world tilt. He ate with the dockworkers, heads bent low over chipped bowls, their Spanish too quick for him to catch more than a word here and there. Still, he laughed when they laughed, and for a few hours it almost felt like belonging.

The sea helped too. He’d sit on the seawall in the evenings, watching the pelicans plunge headfirst into the surf, wings folding at the last second before they vanished beneath the water. They always came up with something wriggling in their beaks. There was a lesson in that, though Sam couldn’t decide if it was about patience or inevitability.

At the cantina, the radio was always on, static cutting through ballads and soccer broadcasts. One night it carried news from the north, snippets about the Olympics. He didn’t catch the details at first, half-listening while nursing a beer warm from the Baja heat. But then the name came clear enough through the crackle: Jessica Sanchez.

A Mexican newspaper lay folded on the bar, headline splashed across the front page. He slid it closer. The photograph was grainy, black and white, but clear enough: a young woman, arms raised, face fierce in its determination. The caption said she had taken silver in the heptathlon, not gold, but close enough to shock the world. “The pride of the Americas,” the article called her.

Sam stared at the picture longer than he meant to. Something in her expression caught him, the grit, the refusal to break. He didn’t know her, didn’t know her story, but the image stuck with him. For a moment, he wondered if she had someone waiting for her in the stands, someone who would hold onto that silver medal like it was salvation. Then he folded the paper shut and pushed it away. Just another headline. Nothing to do with him.

Another night, he found a different newspaper crumpled under a barstool. The date was weeks old, but the byline caught his eye: Olivia Reyes. He remembered the name from San Francisco, a journalist who’d sniffed around city hall, asking dangerous questions. Her latest exposé was on Vanguard Biotechnics, a biotech company accused of running human trials without consent.

He skimmed the article, the words heavy with outrage. Patients vanishing from clinics, records doctored, experiments whispered about but never proven. It sounded like conspiracy theory, except Olivia’s reputation was solid enough to give it weight.

Sam folded that paper too, slid it into his duffel without really knowing why. He told himself it was habit, the same instinct that made him jot down license plates in his notebook, long after the case was dead.

La Paz dulled the edges of his grief, but it never erased them. He drank beer by the shore, watched the sun sink red into the Sea of Cortez, and told himself this was what he wanted, to be nameless, faceless, forgotten. To die in a place where no one knew who he had been.

For a while, he almost believed it.

* * *

The sun bled out over the Sea of Cortez, the horizon a smear of red and orange that burned too bright to look at straight. Sam walked the uneven steps up to his rented room above the cantina, the air still heavy with fish and diesel from the docks. His shoulders ached from the day’s work hauling crates, his shirt stiff with salt. All he wanted was to collapse on the narrow bed, let the fan clatter overhead, and drink until the ocean in his head went quiet.

But when he opened the door, someone was waiting.

The man sat in the lone chair by the window, his posture too upright, his clothes too clean to belong in La Paz. A suit, crisp despite the humidity. Shoes polished. Hair clipped close. He didn’t bother standing. He just turned his head slightly, eyes sharp and flat, the kind Sam knew well. Government eyes.

“Evening,” the man said, as though they were old friends. His accent was American, the East Coast kind that could pass for neutral if you weren’t listening too close.

Sam shut the door behind him, slow. “You’re lost.”

The man smiled faintly. “Frank Doyle. DEA.” He reached into his jacket and pulled out a wallet, flashing the badge just long enough to confirm the claim before slipping it away. “I’m not lost. I’m exactly where I need to be.”

Sam dropped his duffel on the bed, the thud loud in the small room. “I don’t know what you think you’re doing here.”

“I know exactly what I’m doing.” Doyle leaned back, folding one leg over the other. “You can drink yourself to death in paradise. Or you can do something useful with what you know.”

Sam let the silence sit. Outside, the jukebox downstairs groaned through a bolero, the bass faint through the floorboards. He crossed the room, poured tequila into a chipped glass, and drank. “You’ve got the wrong man.”

Doyle’s eyes followed him. “No. I’ve got the only man who knows Caruso’s operation from the inside. You know the docks. The unions. The shell companies. The men who carry the crates. You watched him grow roots in San Francisco. That makes you valuable.”

Sam snorted, pouring another glass. “Valuable? My own department cut me loose. My wife’s dead. My kid’s gone. I’m not valuable to anyone.”

“Caruso thought you were valuable enough to break,” Doyle countered. His voice never rose, never pushed—it just landed, steady and inevitable. “That tells me all I need to know.”

Sam stared at him, the tequila burning in his throat.

Doyle continued. “We’ve got shipments moving through these waters. Cocaine, heroin, whatever you like. Some of it runs straight through Caruso’s lanes. We want to cut them off. But we can’t do it officially. Too messy. Too many hands on the payroll. We need men off the books. Men who can do the kind of work no one else is willing to put their name on.”

He reached into his jacket again, but this time it wasn’t a badge he pulled out. It was a folded envelope. He set it on the table, the paper thick, the corners creased. “It’s dangerous. It’s dirty. But it pays. And it keeps you alive a little longer.”

Sam didn’t touch it. He stood at the window, staring out at the sun dying over the bay. The water caught the light and turned to fire, and for a moment he wondered if he should just walk into it and let it swallow him.

“You think you can disappear here?” Doyle asked, his tone almost pitying. “Caruso’s reach doesn’t stop at the border. Men like him don’t let ghosts stay buried. You sit here long enough, he’ll find you. Or his money will. And then you’ll be just another body washed up on the beach.”

Sam said nothing. The bolero downstairs shifted into laughter, glasses clinking, the life of men who still believed tomorrow might bring something better.

Doyle rose, smoothing his jacket. “Think about it. You want to keep running, keep hiding, you can. But you and I both know you didn’t come this far just to vanish.”

He moved to the door, opened it, and paused. “When you’re ready, you know where to find me.” Then he was gone, the sound of his polished shoes fading down the stairs.

Sam stayed at the window, glass in his hand, staring at the last streak of red slipping beneath the horizon. He didn’t open the envelope. He didn’t need to. The weight of it on the table was enough, heavier than the revolver buried in his duffel.

He lifted the glass, drank, and kept his eyes on the dying sun.

Please sign in to leave a comment.