Chapter 2:

The Colonel’s House

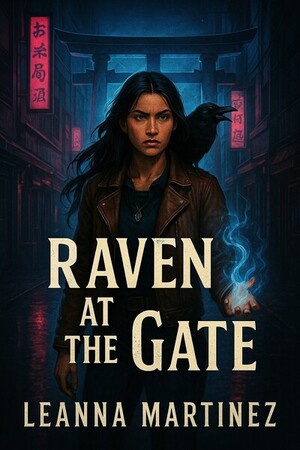

Raven at the Gate

Raven stepped out of the plane and descended the stairs into the misty rain. She carried with her a small duffle that contained everything she owned. Everything else had been consumed by the fire, the same fire that consumed her mother.

She walked slowly towards the terminal building, letting the rain embrace her. The arrival lounge at Yokota smelled like disinfectant and jet fuel, floors shining with rain tracked in from the tarmac. People moved with practiced purpose. Raven stood there with her duffel slung cross-body and the weight of a long night behind her eyes, waiting for a man she hadn’t seen since she was four.

They didn’t send a father. They sent a sign. YAZZIE, R. written in neat black marker, held by a woman with an immaculate bun and a uniform pressed into perfect planes.

“Miss Yazzie?” the woman asked, stepping forward. “I’m Captain Aki Morimoto. Your father sends his apologies. He's still in a briefing.”

“He’s been in one for thirteen years,” Raven said before she could stop herself.

Aki’s smile held, but it fixed a little, as if she’d pinned it with a paperclip. “He’s looking forward to seeing you.”

“Sure.”

Aki relieved her of nothing, not her bag, nor her grief, and led her through glass doors into clean rain and the tidy geometry of the base. The car was as disciplined as its driver. It was a gray sedan with a faint smell of new upholstery and damp wool. Wipers beat time across the windshield while the world outside reframed itself into Japan. There were white umbrellas bobbing at the gate and bicycles under plastic covers. Rows of vending machines glowed like small shrines in the drizzle.

“You’ve had a long flight,” Aki said.

“Felt longer.”

“Tokyo can be overwhelming at first. People usually settle in quickly though.”

“I’m not people,” Raven murmured, forehead to the cold window.

Neon kanji flickered across the glass, reflected backwards and unreadable, as they left the base and slipped into Tachikawa’s streets. Raven traced a finger along the fog of her breath, drawing nothing, erasing it with her sleeve. Her pendant warmed under her palm through the jacket giving a small pulse, faint and steady. It was in the same tone she’d heard in the engines. The same tone that lived behind her ribs.

Captain Morimoto was the first to break the silence. “He’s a good man,” Aki said after a while. “Colonel Yazzie.”

“That’s what people say about men they don’t actually know,” Raven said, turning to look at Ali for the first time since she got in the car.

Aki glanced over, then back at the road. “He works very hard.”

“Great,” Raven replied with a high level of sarcasm, before turning her attention back to the window and the reflection of the world she had been forced into.

They passed a park with winter-bare trees dripping and a kindergarten whose mural of smiling animals looked waterlogged but cheerful. Everything here had a gloss and an order. The edges clean, and the surfaces wiped down. The desert had remembered her with wind and grit, but this place felt like it forgot on purpose.

The administration wing was warmer than the rain and louder than the car. The air was full of the sound footsteps echoing down endless hallways and the mechanical murmur of printers. Aki walked her past a bank of framed maps of the Pacific theater and flight corridors, each with a spray of pins like constellations. She left her in a waiting area under a fluorescent buzz that brought out the ache behind her eyes.

“He’ll be with you as soon as he can,” Aki said. “There’s a vending machine around the corner. Coffee isn’t good, but it’s hot.”

“Thanks,” Raven said, which was easier than saying nothing.

She sat with her duffel between her boots and watched minutes fall off the clock with the precision of a metronome. Soldiers drifted past in currents. A television in the corner murmured Japanese news with the sound off. The screen showed a weather map with rain icons marching east, and was full of blue banners and scrolling text. The air smelled faintly of toner, but was mostly sterile. Her mother’s jacket didn’t belong here, its smoke-and-sage scent was a contradiction in a room designed to be scentless.

She woke her tablet and scrolled through messages she already knew by heart. She skimmed past the social worker’s tidy sentences giving travel instructions. She even skimmed past her father’s email it was short enough to fit in a breath.

We’ll get you settled. Structure will help. Yokota’s different, but safe. Structure. The word crawled into her stomach and made a fist.

She flicked past it to her grandmother’s last text, months old and singular, the little gray speech bubble a world she couldn’t step into anymore.

Remember the song, Raven. It protects you. It also remembers you.

Her earbuds were long dead from use and stowed in her pocket. Yet they hummed faintly against her thigh, as if some ghost signal had found them. She pressed her thumb to the pendant around her neck until the phantom sound faded, only to be replaced by the buzz of the fluorescent lights that hummed in time with her pulse.

Three hours looks like: one paper cup of bitter coffee that cooled too fast, thirty-two people who didn’t look at her, two who did and then looked away, and the quiet realization that this, right here, was the family reunion.

A file folder dropped in the next office with the clean slap of a door closing. She flinched anyway.

“Raven.”

She stood before she decided to. The man in the doorway wore her surname crisp on his chest and time drawn close across his face. The uniform fit like he was born in it; the aftershave and paper smell came with him, clean and dry and strangely empty. His hair had gone more gray than she expected, his eyes less everything.

“You’ve grown,” he said, as if they were picking up a conversation from last week.

“That happens.”

“I’m sorry to keep you waiting. Things move fast here.”

“Not fast enough to meet your kid at the airport.”

Something moved in his eyes, an apology, maybe. Raven had hoped for one at the least. Instead, he gestured to the door, his palm slicing the air in a precise line. “Let’s get you home.”

The word hit her wrong. Like a shoe handed to a foot that wasn’t the right shape.

* * *

Rain had thinned to a mist by the time they reached the off-base apartment. Three stories, beige tile, a neat double row of potted bushes obedient under the eaves. Inside, the corridor smelled like disinfectant and climate control, the kind of air that never made choices. Her father unlocked a door with a rapid soldier’s economy and stood back to let her in.

The living room was a press release. There was a sofa, two chairs, a coffee table, and a floor lamp. Government-issue art hung on the walls. The most prominent one was a mountain print made with abstract shapes. They were all hung exactly straight with the precision that was worthy of a man that stressed the importance of structure. On a sideboard, his framed commendations stood at attention beside a group photo of men in flight suits squinting into the sun. There was nothing that showed a birthday party, a lost tooth, or a first day of school. There were no photos of a girl in pigtails he hadn’t been around to braid.

“It’s not much,” he said, locking the door as if this would lock them into some shared timeline. “But it’s safe. You’ll have structure here.”

“You really like that word.”

“Structure keeps people from falling apart.”

“Maybe some things need to,” she said, turning away to hide her true feelings.

He breathed in a slow steady, measured breath before crossing to the kitchen. “There’s tea,” he offered. “Or water.”

“Water is fine.”

He brought it in a glass that had never been anything but a glass. She held it like it was a prop. He watched her not drink it.

“Your school records transferred,” he said in a matter of fact tone. “You’ll start at Tachikawa International. They’re used to dependents, to transitions.”

“Great. I’ve always wanted to be expected,” she replied with more sarcasm than genuine interest.

He set the mail down in a square stack, squared it again. “We’ll start over,” he said, the words too smooth to be new. They were words he had obviously rehearsed

“We never started anything.”

Silence sat between them and took up the good chair. She walked the room because standing still made the air heavy. A narrow metal cabinet tucked beside his desk caught her eye. It had a small brass plate screwed into the door. ‘D-4 ARCHIVE’ was stamped on it clean and impersonal.

“You hiding ghosts in there?” she asked, not looking at him fully, not not looking either.

His answer came too quickly to be casual. “Classified material. Don’t touch it.”

She lifted her hands an inch, palms out. “Wouldn’t dream of it.”

He looked like a man in an exploding cockpit, choosing which instrument to save. “I’ll be at the office most days. Captain Morimoto can assist if you need anything. There’s a grocery on the corner. The neighbors are quiet.”

“I’m excellent at quiet.”

He nodded as if that were a skill he could list on a form. “Food?” he tried. “There’s a place, udon. Simple.”

Her stomach had opinions, but none she wanted to share. “Maybe later.”

He looked at his watch, a motion as smooth as his earlier apology. “I’ll let you rest.”

“Sure.”

He showed her the small bedroom like a realtor. There was a bed, a desk, and a wardrobe. There was not much else. The window of the room overlooked rooftops and a tangle of power lines. The sky was a pale lid pressing down low. An air purifier purred in the corner, a white box deciding how the air should be. A stack of textbooks sat squared on the desk. There were the typical math and literature books, a Japanese workbook whose cheerful cartoon on the cover felt like a joke, and a book on magic theory. In New Mexico, only a few had awakened magic abilities and even fewer taught it. Japan, however, was ground zero for the awakening. Here nearly everyone had magic abilities of some level. Magic was taught in regular schools, but few were able to master it.

“I’ll be back around twenty-one hundred,” he said, lingering at the door as if something might arrive to fill the space if he waited. Nothing did. “We’ll figure a routine.”

“Of course we will.”

He left on soft soles. The latch clicked with the finality of a period.

Raven didn’t turn on the light. She dropped the duffel at the foot of the bed and set her mother’s jacket over the chair. It didn’t belong in the room any more than she did. Its scuffed nylon and half-melted patch was a little slice of unruly against the beige of the room.

She cracked the window for air and leaned her forehead to the cool pane. The rooftop antenna across the narrow gap held a crow like a mantle piece. It fluffed once, rain ticking from its feathers, then settled to stillness so complete it might have been carved there. When lightning flickered a soft sheet far off, its eyes caught the flash and threw back a color that wasn’t in the storm. For a second, a tiny seam of turquoise reflected in its eyes..

“Not here,” she whispered, and the glass took the fog of her breath and made a pale ring of it, then let it fade.

She unpacked nothing beyond a toothbrush and a change of socks. The rest could stay in the duffel until this place decided what it was. She sat on the bed and sank into the unfamiliar give of a mattress bought to satisfy a line item. The apartment hummed with the mechanical sounds of the air purifier, refrigerator, and distant plumbing in the walls. All the sounds that pretended to be silence if you didn’t listen.

On the desk, a folded piece of paper waited. It hadn’t been there a moment ago. Raven left it alone until not leaving it alone felt like the wrong choice. It was a note written in Aki’s tidy hand.

Welcome, Miss Yazzie. If you need anything, call my desk. —A.M.

The kindness landed and didn’t know where to sit. She lay back without undressing, hands folded over her stomach as if some nurse had told her to be still. Her eyes found the faint seam where the ceiling met the wall and stayed there until the seam blurred. Somewhere below, a scooter coughed and faded. Somewhere above, footsteps moved once and stopped. The rain softened into whatever came after.

The crows started up near midnight. It was not the harsh caw of daylight, but rather a softer sound that was layered and intimate. More like the way people talk in another room when they think you’re asleep. It was not words, and not music. It was something in between. It threaded through the hum of the air and slid under her ribs, matching the old rhythm that never left her.

She closed her eyes and told herself it was just birds. That the pendant wasn’t warm against her skin because of anything but her own body. That locked cabinets were just metal and screws. That tomorrow would be schedules and forms and instructions, and nothing in the spaces between. Her mind didn’t believe her. The apartment didn’t, either. It held its breath the way desert does right before the wind remembers it.

Raven turned her face to the wall. She breathed until the hum was only hum and the voices outside were only birds. Sleep came the way it had been coming lately, like a compromise, like a hand you didn’t really want to hold.

Before it took her, a small weight shifted on the antenna, and the crow tilted its head toward the window. If anyone else had looked, they would have seen only rain glossing black feathers, only a bird watching its reflection in glass. But for a heartbeat, in the thin place between waking and whatever waited, the glint in its dark eye picked up a color that wasn’t the streetlight, wasn’t the storm.

Please sign in to leave a comment.