Chapter 35:

Chapter 35 — The barth of Spartor

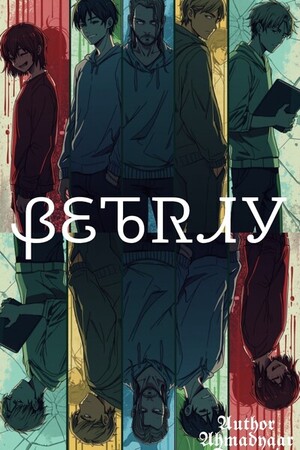

Betray

Night had already settled over the village where the Tinkerer lived. Lantern light winked from crooked windows, and the alleys smelled of cold smoke and oil. Corvo trudged home with his satchel slung over one shoulder, homework finished, or at least finished enough.

“Homework?” the teacher had scoffed that morning. “What’s that?” Corvo had laughed it off then, glad to be free. Now, walking under a sky the color of old iron, he muttered to himself. Who made this stupid school anyway? he thought. I hate it here.

He rounded a corner and froze. Three men were clustered around a younger boy, riffling through his pockets. The boy’s breath came quickly; his hands trembled. One of the men shoved him roughly. Corvo’s first instinct was to keep walking, less trouble that way, but something in him tightened like a drawn string.

The shortest of the three pulled a small knife and tossed it carelessly toward Corvo as if daring him to stop. The blade missed by inches and clattered against the cobblestones. Corvo didn’t think, he moved. The knife landed at his feet. He bent, scooped it up, and the world narrowed to the weight and coldness in his palm.

“Now I’ll be the hunter,” he said, shockingly calm, more to himself than anyone else, “and you’ll be the prey.”

The three men exchanged glances. For a heartbeat they hesitated, then fled, not because the knife was especially fearsome, but because Corvo’s eyes had something in them the alley had not seen before: a steady, dangerous quiet. He watched them go until their shadows dissolved into the night, then let out a breath he hadn’t realized he’d been holding.

At home, Corvo set the knife on the workbench beside the battered tools and tried to put the night behind him. But memories have a way of surfacing, uninvited and in sharp detail.

He remembered a river, wide and black with winter reeds, the air sharp with the smell of wet earth. He and a girl had been walking along the bank when she slipped. He jumped in without thinking, the water closing cold and sudden around them. He’d grabbed at long strands of what he had believed to be weeds, only later, as months and faces blurred, did he realize those tangles had been hair. He had been holding her hair as he pulled her out. For one terrible moment afterward he had thought the river had taken something else from him.

He’d seen a fisherman after that, months later, when the world had gone on its slow, indifferent turn, and asked if the river had long strands of grass. The man had looked at him puzzled and said there were none. He’d cried then, alone on the riverbank, remembering the weight of hair in his hands. That image never left him. Maybe, Corvo thought, if I get rich, if I can afford people to search, then maybe I can find her. Maybe I can bring back what was lost.

Outside the village, in another place within the anims, a different kind of night ended in blood and silence.

Hun was eleven, thinner than a twig, his ribs outlined under threadbare cloth. His parents were sickly and kind; their faces had the tired softness of people who had given everything to a field and received little in return. That night a group of kidnappers came, faces half-hidden, words cruel. They took the family like a plucked handful, laughing about the money they’d get.

Hun watched, hollow-eyed, as the men tied his parents and dragged them away. In the dim light he could see they were already broken, eyes dull, movements slow. The kidnappers joked that the pair wouldn’t fetch much, and with a callousness that smelled of iron, they left the little boy alone in the hut.

His father, in a voice so soft Hun barely heard it, said, “I came from a land called Spartor.” The words meant nothing to Hun, and yet they landed with the force of something important. His mother clutched his arm, and the room seemed to tilt, two holes opening in the sky above them, one white as bone, the other black as ink. Chains, cold and impossible, writhed into being and wrapped themselves around his parents’ wrists like living things.

They did not scream at first. The father’s voice was a rasp: “You must forget… so the power can pass.” Hun stared, too small to make sense of it. The chains tightened, not in rage but in ritual, binding and humming with a terrible purpose. The father’s eyes found Hun’s, fierce, pleading. “Take our lives,” he whispered, “so it will live in you.”

There wasn’t time to understand. A stranger, one of the kidnappers, or some greater horror that had come with them, spoke in a voice that sounded like gravel. “The slower you make us suffer, the more pain you’ll feel,” he said, and without ceremony he brought down a stolen hoe. The blows were precise and final. The hut ugly with sound and then still.

Hun fled into the night with the tool, a sick keepsake, heavy in his small hands. He ran until his lungs burned and his feet bled. In the dawn that followed, he hid among the rows of his father’s ruined crops, and the world looked different: the bodies that had been his parents were only husks now, and the place that had been home was a map of absence. The name Spartor had lodged like a stone in him. He did not know what it meant yet, only that something old and terrible had been planted inside him with iron and blood.

Back in Corvo’s village, he ran his fingers along the knife’s edge, thinking of summer fairs and selling small inventions, things people would want. He would make something the villagers liked, he told himself. He would earn enough to hire searchers, to travel, to pull answers up from places where rivers and memory mixed.

He closed his shutters that night with the knife under his pillow and a single, childish plan lodged in his chest: find what was lost, or lose himself trying.

© 2025 Ahmadyaar Durrani. All rights reserved.

Please sign in to leave a comment.