Chapter 12:

Harbor and Inn

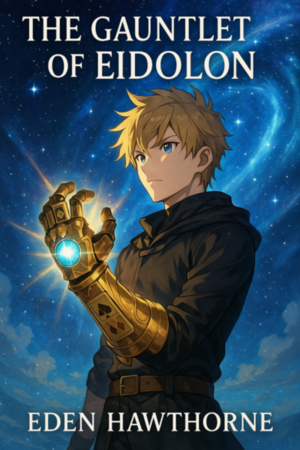

Gauntlet of Eidolon

By the time dusk bled into true evening, the giant was lashed, levered, and bullied into a position that would let the tide and a team of oxen drag it across the mud to a makeshift pyre someone had sensibly started on the stony ground above the high-water line. Brynhild dismissed teams in threes to wash and eat and not collapse. When she turned toward them her hair had come loose in a few places and the wind had found it; she looked like a painting the sea would commission.

“I’ve arranged rooms,” she said, as if rooms were just another logistics problem solved with rope and patience. “Halfdan, Lili, we’ll reconvene in half an hour at the inn.”

Lili caught fast to Halfdan’s sleeve. “Bedtime tales,” she declared with solemn weight, then turned to Brynhild. “But from the fiery one. His voice is pleasant.”

Brynhild, who clearly found Lili’s response amusing, did not smile and somehow conveyed the experience of smiling perfectly. “The fiery one may be prevailed upon.”

“Thank you,” Halfdan said, and meant it too much for the words not to be clumsy. Brynhild nodded with that not-a-smile-but-smiling look of hers. As they made their way toward the harbor, the pyre was already burning, the air gathering the sharp, resinous scent of rosemary and smoke.

Halfdan wondered why rosemary. Did the plant have some purifying property… or did giant corpses just naturally smoke like an herb garden? He filed the question away with all the other strange things that had happened in the last, gods, hours.

Not even ten hours ago, he’d been having dinner with his family in Draven.

He sighed and took Lili’s hand as they walked toward the inn, past the first of the lamplighters working along the lane, past a woman pouring a bucket of clean water across a stoop as if she could wash the day from the world brick by brick. Behind them, along the river, men’s voices rose and fell in rough counterpoint with the crackle of wood. The dead thing would be a memory by morning and a story by next week. Halfdan could feel the bruise beginning to form along his body; the ache would have its say later. For now, there was the warm promise of bread, a chair, and the first honest meal in what feels like years.

The inn swallowed them into warmth and clatter. A low ceiling held the heat close, beams dark with smoke and years. The common room’s long tables were crowded at their edges and emptied in their middle where the day’s labor had left gaps. A woman with sleeves rolled to the elbow carried a tureen the size of a helmet and poured stew into bowls with a precision that made every portion a small promise kept. A boy darted through with a bread-basket clutched to his chest like loot from a raid, vanishing and reappearing with uncanny timing. The smell of rosemary found them again, now honest and clean from the kitchen instead of perfumed pyres.

He and Lili sat at the long table, waiting for their companions. Lili asked him questions about his home, and he wasn’t sure which one to talk about: Halfdan Skarsgård’s home on a distant planet with a name that couldn’t be more obvious, or Alexander Di Luca’s home in a city steeped in treachery and deceit.

He decided Alexander was the safer choice. At least that way he wouldn’t have to explain Wi-Fi, the internet, or video games, things that had taken up an embarrassingly large part of Halfdan Skarsgård’s life.

So he talked about old Tom, who was proper and serious but always seemed to know every juicy story, almost omniscient with how much gossip he carried.

Then the air grew heavier, pressing down on his lungs as the last time he’d seen Tom snapped back into focus.

He knew.

He fucking knew.

The rush of blood in his ears drowned out the world.

Who else? Who else knew I was a lamb raised to be slaughtered?!

The door opened, and a cold breeze slipped in, cutting clean through Halfdan’s spiraling thoughts.

At the threshold, Brynhild paused and glanced back at the street, her face turned to profile in the light, beautiful in that distant, unapproachable way that belongs to saints in paintings and to women who have taught the wind its manners. For a moment, time slowed down and all he could see was the light caressing her face..

Then she stepped inside, and the inn’s light and clatter sharpened around him.

Halfdan almost didn’t notice Lukka following behind. Lukka, however, noticed that he hadn’t, and his half-amused, half-annoyed smirk said so plainly.

Brynhild spoke to the innkeep in a tone that said arrange this and then stepped aside to let it happen. The innkeep bowed his head, and his hands went faster; benches around a back-corner table cleared as if the air itself had shouldered the men away. She signaled for Halfdan and Lili to join them, and they rose from their seats without a word.

Lili walked like someone stepping into a story she had been promised, chin lifted, eyes too wide and too bright, trying not to look like she was trying not to stare. Halfdan kept a half-step behind her without meaning to; he felt like a cloak, a habit worn in one life and remembered too easily in this one.

They sat. Bowls arrived. The stew was thick and warm, a fisherman’s compromise between generosity and mathematics: potatoes cut into honest cubes, fish that had never seen a spice jar until the rosemary met it, and a curl of orange peel to brighten the tongue like a joke told by a solemn uncle. Lili took one spoonful, blinked, and then began to eat with purpose. Lukka ate slowly, as if weighing and judging every spoonful before allowing it passage. Brynhild ate with the attentive neatness of someone who had been hungry once and learned not to advertise it.

Halfdan discovered belatedly that the problem with being fifteen again was that his body had its own opinions about appetite. He had intended to maintain a shred of dignity and failed almost immediately. The second bowl might have been an accident. The third was a declaration of principles.

Someone set down a plate of flat bread, blackened in places and fragrant, and a round loaf with a crust that crackled like it had secrets worth sharing. Lili tore a strip from the flat and a heel from the round, and by this small, precise sacrament declared the meal properly begun.

Their table became a small island in the room. Men came and went, scraping benches, gulping ale, trading the coarse chorus of congratulations and complaint that follows hard work well done. The inn’s old hound performed a brisk patrol under the benches, decided their table owed it nothing, and padded off to richer prospects. Near the hearth, a woman told a low story to a man with his boots off, staring into the fire with the blank gratitude of the exhausted. Whenever laughter rose somewhere, Brynhild’s gaze strayed toward it and then back, as if tallying the harbor’s spirit on some invisible slate.

“More?” the innkeep asked, hovering with the ladle. Lili nodded as if she had been asked something philosophic and the answer required solemnity. Lukka waved the man on with a grunt. Halfdan tried to say no, thank you, and his hand betrayed him by tilting the bowl forward.

It should have been a cheerful meal, and was, but it was also a quiet one, the kind of quiet that settles when the day has already taken its share from everyone at the table.

It was Lili who brought the light back into it without trying. She set her spoon down with the air of a magistrate and said, to no one in particular, “Round bread for stories.” Then she turned to Lukka with the expectant authority children wield like a scepter.

“Will you tell one?”

Halfdan was prepared for Lukka to refuse. Lukka did not look like a man who told stories; he looked like a man who didn’t believe stories had done him many favors. To his surprise, the red-haired warrior inclined his head as if accepting a commission and briefly lifted his eyebrows at Brynhild. She made a small gesture, permission, but also an order to mind his tongue. Lukka thought a moment, rubbed his jaw with two fingers, and began.

He told it plainly, in the stripped-down cadence of a soldier’s rather than a bard’s. But the plainness suited him; the words sat square on the table like blocks a child might build with, and somehow the tower rose all the same. It was about a river that pretended to be a road, and how men followed it thinking they would arrive somewhere only to discover that they had been traveling in circles because the river was shy and did not like strangers. It featured a fox who lied because it was bored and a farmer who told the truth because he didn’t have time to remember lies. Lili laughed when the fox’s cleverness flipped into foolishness. She listened wide-eyed when Lukka described the sound a spring makes under snow. The punch line, if that quiet, odd little tale had something so loud as a punch line, was that the farmer built a bridge, which the river tolerated because it respected workmanship, and the fox used the bridge and decided that some honest things were amusing enough on their own.

Halfdan found himself smiling despite the day. It was not the story he would have told, if he had told one. It was better here. Lukka’s voice had a rough burr to it that made the river’s shyness plausible and the bridge an act of courage. Lili’s head nodded into sleep at the end as if it agreed with the moral and didn’t need it spoken aloud. She rallied long enough to ask if the farmer had named the bridge. “He didn’t,” Lukka said. “But the village did.” That satisfied her in some deep way, a proper division of labor between private doing and public naming, and she surrendered.

Brynhild rose, and the room rose a little with her. “Come, little Lili,” she said, and her mouth softened on the name without meaning to. “We have a bed for you.” Lili wobbled upright, the round heel of bread clutched in one fist, the other hand finding Brynhild’s without looking. “Lukka,” Brynhild added, “go with her. Give the innkeeper his fee if she demands three extra pillows or a window that faces the moon.”

Lukka’s mouth twitched toward an answer that would have been insubordinate anywhere else and here qualified as affection. “Aye,” he said, and scooped Lili neatly under one arm as if she were a bundle of reeds and not an opinionated person. She made a small protesting noise of dignity and then leaned into him anyway, eyelids lowering the way fireplaces do when they have just enough wood left to be comfortable.

Halfdan watched them. Envy stirred, small, ridiculous, the kind of emotion a child mistakes for something bigger, and he was at least old enough somewhere inside to recognize it for what it was.

She looks far too comfortable with a man she just met, he thought, then snorted quietly at himself. You met her half a day ago, Skarsgård. She’s not your little sister. Grow up, tolerably swift Hal.

He tore another piece of flat bread and kept eating.

Brynhild remained standing for a moment, watching the stair until Lukka’s boots passed out of hearing. Then she turned her gaze upon Halfdan; the turn itself felt like a courtesy, not a demand. “Will you sit by the fire with me?” she asked.

He had already been sitting. What she meant was stay. He nodded, tried to make it look like consent and not relief, and stood to carry his bowl, breat and cup to the hearthside bench. She reclaimed her sword from where she had set it by the door; she did not lay it down carelessly, she set it within reach and sat across from him, the hearth painting slow gold across the white of the steel and the carved work of the guard.

Please sign in to leave a comment.