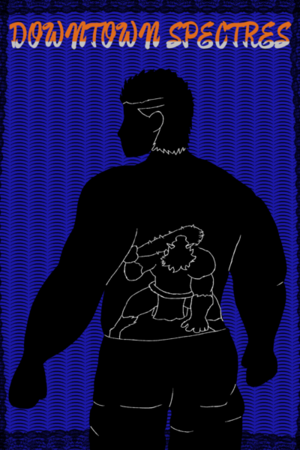

Chapter 21:

Allegory of the Cave

Requiem of the Fallen

Pravuil left Munkar's foolhardy assault behind. In a thought, she followed the divine thread back to Heaven. There, the world was resplendent. The glory was near, and golden light filtered through a world of marble, filigree, crystal glass, and drifting cloud. The Lord stood on the horizon of the celestial East in pensive meditation, the sun of Heaven at an eternal dawn overlooking the vast expanse of the Silver Sea of Silence and the rising, vaporous plumes of the Pillars of Creation that shone as rainbows cast by a million twinkling stars.

To the north stood the muster-grounds, the forums and amphitheaters where the Angels gathered, and to the south the divine apartments and places of rest and healing where one might meditate upon the Mysteries in peace. Behind Pravuil, in the west, spread the lacunae pools that gazed down upon Earth and, among them, the houses of knowledge where Pravuil herself so often conducted her business, recording the Truths of Heaven and Earth.

All these were ordinary sights for Pravuil. But Pravuil looked outward with skeptical eyes. The glory was there, as it always was, so easily ignored. But Pravuil considered Penemue's communication, and the lengths that she had gone to in order to deliver it through a concealed mechanism. “The halo lies.” A critical blasphemy, and as evidence words clearly intended to say the same that reached Pravuil's ear as nonsense when the tap-scratch of Mores code told a different story.

It wasn't much evidence. Penemue could have said anything, but Penemue had been the best of all of Pravuil's students, the most dedicated to knowledge and the purity of reason. For some reason, she had Fallen. She had rejected the glory and severed herself from God's grace. Pravuil saw this first-hand, confirmed the whisper that her student's halo was shattered and lost.

But Pravuil also considered that one of the first lessons she had taught Penemue, one of the first lessons she taught to any angel who sought to tread the path of wisdom, was an old human thought experiment known as the Allegory of the Cave – suppose that a group of mortals were seated trapped and their heads unable to turn, so that all they could see were shadows cast upon the wall of a cave by light behind them. Would they know the real world from the shadows? And could one who was freed from his bonds prove to the others that there was a world of greater substance?

Interesting, from a human perspective, and many aspirants gave up pondering the questions of the allegory, deciding that they were not made to conduct philosophy. There were two attempts at answers that Pravuil remembered particularly intently. Ramiel, who had never been much of a student, said that it was the glory that separated truth and substance from shadows cast upon the wall, and that even a human would understand on an instinctual level that they were lacking the presence of God if they were forced to endure a world in shadow play, even if they did not have the words or concepts to express what they were lacking for the want of having experienced it.

Penemue's first response to hearing of the Allegory of the Cave was simply to suggest that they could test it experimentally. When prompted, she had followed the lines of reasoning to conclusions both orthodox and heterodox, but simply suggesting an empyrical solution was not something that Pravuil had heard before or sense.

That was what Penemue had always been, one who learned by her senses above being one who could conduct deduce or induce. When a problem presented itself to her, her first instinct was to examine it in the material sense, collecting every possible evidence and forming her beliefs based on the same. Why had one such as her done this thing, and cast herself from grace? Because the halo lies. Penemue must have believed that much, and Penemue believed evidence above all.

From the theoretical standpoint, it was possible. Pravuil knew, as all angels did, that her halo was made to intercept what she would see or hear. The halo, and not the world, was her primary source of sensory information. The wisdoms said that this offered greater truth, to pierce lies and foil deceit, for the glory would, as in Ramiel's answer to the Allegory of the Cave, banish false shadows in favor of the world of substance.

But if Pravuil supposed Penemue's ultimate apostasy, the conclusion that she reached was that it was possible that the halo was, instead of the solution to the Allegory, the Allegory itself, the cave wall on which shadows were cast for angelic eyes.

It was a preposterous postulate, of course, and if any student of Pravuil had ventured as much she would have punished them harshly. For the moment, however, Pravuil was concerned less with truth and more in determining the vector of Penemue's logic. Scholars of argumentative schools could stray into such cursed beliefs if they were not careful, but for an empyricist like Penemue, there would have to be a possibility of retracing the situation to its origin.

As Pravuil pondered this, Lailah arrived. Or rather, what was presently left of the Seraph of Charity arrived. Pravuil had not actually seen an angel in sorrier state – everything below her ribcage was gone, as was her right arm, and the right side of her chest was open while the right of her face was burned black. Some of the attendant Virtues rushed to her immediately, and bore her towards the celestial south, but there was little doubt she would need God's hand to be restored, and Pravuil began to muse on if it was possible for an angel to die of such catastrophic injuries without the common causes of demise in evidence.

It was certain that the heretics were extremely resourceful. Pravuil had speculated that they were utilizing mortal allies empowered through Transference, given the apparent drop in their own physical capabilities reported through every engagement, but had kept as much to herself seeing how dangerously Munkar already wanted to persecute the offense. With Lailah so maimed, it was unlikely he'd escape without sanction, for one reason or another.

All the same, Pravuil turned her thoughts onto the group. Before they betrayed their duties before God, they had been known faintly for their association. They were Angels who had little cause to encounter each other, who came from different ages and different mentors and might have spoken seldom if at all. But in days more recent, they had begun to gather near the shores of the Silver Sea of Silence, watching over it as their recreation.

It was also, Pravuil noted, by the shores of the sea that Haniel's bout of madness had begun. She had raved in tongues, and screamed delusions and blasphemies. But the Lord had forgiven Haniel and made her not just whole, but Hallowed. All the same, the mental sickness that had afflicted Haniel so had its origin in the same region of Heaven that those who turned their backs on the glory, that Penemue who claimed the halo lies, had their interest in.

Could it be possible, then, that there was some infectious vector, some cognitive hazard, that had infested the Silver Sea of Silence?

An angel's halo was part of the glory, a gift from God conferring sight beyond sight. There was a working theory – whatever anomaly could cause this madness was protected from by the halo but, consequently, could not be detected without somehow bypassing how an angel was meant to see the world. What Penemue and the others had done, how Haniel had been afflicted, that was unknown.

But, as quickly as Pravuil came upon that theory, her logic found an error within it. How could such an evil exist beneath the gaze of God? The glory was near here, and the Lord stood most often at the dawn cardinal watching over the Silver Sea of Silence. Surely, it should not have been possible for any evil to escape in a place like that.

Unless, of course, the halo lied.

Pravuil decided two things then. The first was that this was worth investigating. Without more evidence, it was impossible to reach a non-contradictory conclusion. The second was that it would be wisest to not tell any other angel of such an investigation.

She spared a brief thought that such secrecy had a heretical sense to it. But Pravuil only sought the truth, and truth could fundamentally never be wrong.

Please sign in to leave a comment.