Chapter 13:

7. The Alignment of Fear

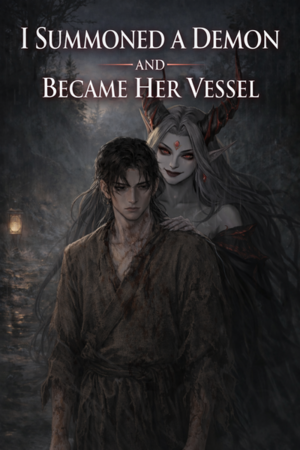

I Summoned a Demon and Became Her Vessel

We were halfway to the Eastern Gate when the Order fractured.

The path to the structural cells was paved in dark, uneven cobbles, slick with the eternal damp of the city’s underbelly. The air here grew colder, smelling of wet earth, unwashed bodies, and the iron tang of old chains. The walls on either side rose high and windowless, blotting out the sunset.

The guards walked with the heavy, rhythmic gait of men delivering a burden to a grave. They did not speak. They did not need to. The stone around us spoke for them. You are ending.

Wei kept his head down. He had accepted the stone cell. It was a punishment he understood. It fit the shape of his life until now: rough, cold, and inevitable.

Then, a voice cut through the gloom.

"Halt."

It was not a shout. It was a word spoken with the quiet, terrifying resonance of high office.

A figure stepped from the shadow of a sub-archway. He wore the robes of the Inner Secretariat, silk dyed a deep, bureaucratic indigo that absorbed the torchlight. He held a slate in one hand and a jade token in the other. He did not look at the guards. He did not look at the damp walls. He looked only at the slate.

"Transfer of custody," he said.

The head guard frowned, his hand resting instinctively on the hilt of his weapon. The friction between the martial and the administrative branches was a structural constant in this empire.

"My orders come from the Chief Examiner," the guard rumbled. "This subject goes to the Isolation Annex. He is a containment risk."

"Your orders are obsolete," the official replied, tapping the slate with a long, manicured fingernail. "The Isolation Annex is for confirmed threats. Violent beasts. Heretics who scream. This subject is..."

He paused, finally looking up. His eyes swept over Wei with a mixture of curiosity and calculation. "...unconfirmed."

"He broke the arrays," the guard argued, stepping forward. "He ate the sound."

"He failed to interact with them," the official corrected. "There is a distinction. If we place him in a suppression cell, and he is not a cultivator, the ambient pressure could rupture his organs. The loss of a unique specimen would be... administratively inconvenient."

The guard hesitated. The logic held. The System did not want to destroy the anomaly. Not yet. It wanted to catalogue it. To break Wei now would be to lose the data he represented.

"Where does he go?" the guard asked, his grip on the weapon loosening.

"The Annex of Quiet Reflection."

Wei looked up then.

The name sounded gentle. He did not know that gentleness is often the most efficient form of containment.

They did not arrest Wei.

Arrest implied guilt. Guilt required definition. To charge a man, you had to name his crime. To name his crime, you had to name him.

Instead, they relocated him.

The order was folded into administrative language so bland it could have applied to a shipment of grain or a damaged relic. For the sake of safety. For the sake of clarity. For the sake of all parties involved.

Wei was informed of the decision, not asked.

We turned away from the heavy stone of the Eastern Gate and moved toward the city’s heart. The environment changed rapidly. The dark cobbles gave way to smooth, interlocking tiles. The air grew lighter, filtered by expensive wards that scrubbed away the smell of the lower city. The frantic energy of the streets faded into a hushed, respectful silence.

The Annex of Quiet Reflection sat apart from the city’s living flow. A euphemism, of course.

It was not a prison. There were no bars, no chains, no overt restrictions. It was a compound of white walls and curved roofs, designed to look like a retreat for weary scholars.

It had windows that let in filtered sunlight. It had gardens manicured to within an inch of their life, where every pebble seemed to have been placed by a committee. Walking paths were measured precisely to discourage wandering without ever explicitly forbidding it.

Containment, at this stage, still believes in cooperation.

Wei noticed the difference immediately. His steps slowed as soon as we crossed the threshold, as though the air itself carried an unspoken instruction to be still.

"Why here?" he asked, looking at the high, white walls that surrounded the garden.

"Because the stone cells were for rejection," I replied. "This is for retention."

He frowned, watching a koi fish swim in a pond that was perfectly circular. "That sounds worse."

"It is," I said. "Rejection implies they want you gone. Retention implies they want to know what you are worth."

The attendants who guided us inside were senior enough to hide their discomfort better than the juniors, but not well enough to erase it.

They wore soft slippers that made no sound. They did not walk too close to Wei. They did not walk too far.

Their spacing shifted subtly, constantly recalculated, as if no one could decide what the correct distance was.

A servant approached with a tray of tea. Her hands trembled slightly as she offered it to Wei.

He reached for the cup.

I watched the interaction closely.

His fingers brushed the porcelain.

For a microsecond, the cup seemed to hesitate in reality, the steam swirling in a pattern that defied the wind. Then he grasped it. The servant pulled back quickly, as if she had just fed a tiger from her palm.

They spoke to him politely. They avoided speaking about him.

That, too, was a change.

In the cells, he would have been an object. Here, he was a guest who could never leave.

The chamber assigned to Wei was spacious, clean, and deliberately undecorated. Nothing personal. Nothing symbolic. The walls were inlaid with patterns of silver and jade, treated to dampen spiritual resonance without suppressing it entirely.

Enough to observe. Not enough to interfere.

Surveillance disguises itself as care.

Wei set his pouch down on the low table and looked around. The room smelt of nothing. Not dust, not flowers, not cleaning agents. Just absolute, terrifying neutrality.

"This is temporary," he said. It wasn't quite a question. It was a plea for parameters.

"For now," I agreed.

He sat, hands resting on his knees.

His posture was careful and contained, as though he were trying not to disturb the equilibrium of the room.

He looked at the window. The view showed a single, perfect plum tree. It was beautiful, and it was entirely artificial. I could see the root grafts binding it to the nutrient feed beneath the soil.

"They changed their minds," he said after a moment. "On the road."

"Yes."

"Why?"

"Because they are afraid," I said.

"Of me?" He looked at me, his eyes wide and dark.

I shook my head.

"Of uncertainty. If they put you in a dungeon, they define you as a criminal. Criminals are simple. You execute them, or you release them. If they put you in a palace, they define you as a guest. Guests are simple. You honour them, or you bribe them. Here, you are neither."

I walked to the wall and ran a hand over the silver inlay. It buzzed faintly against my palm, transmitting data back to the central archive.

"You are a record waiting to be identified," I finished.

That was worse.

Wei understood hunger.

He understood pain.

He did not understand being a character in an analogy he couldn't see.

"What do I do, Mistress?" he whispered.

"You exist," I said. "That is what is breaking them."

Outside the chamber, the discussion had already begun.

It never happened in one place. Authority preferred fragmentation. Committees split responsibility the way water splits light. Each refracted the problem differently, each convinced their angle was correct.

I listened to them.

Not with ears, but through the vibrations in the stone, through the fluctuations in the local Qi field.

The Annex was built to listen to the prisoners, but the architecture worked both ways. The stone carried the whispers of the jailers just as clearly.

…

One faction, holed up in the Archive of Lineage, argued for Latent Divinity.

"The readings resemble suppression only seen in sealed bloodlines," a woman insisted. I heard the rustle of her silk sleeves as she tapped a diagram spread across a teak table. "If his ancestry includes a dormant celestial heritage, the instruments would naturally fail to measure it. The infinite cannot be scaled by the finite. He is not empty; he is too full."

"Then the Heavens would have reacted," another voice interrupted, dry and sceptical. "Thunder would have struck. Omens would have fallen. They have not."

"Yet," the woman countered. "Perhaps the Heavens are waiting."

They look for gods because they fear a universe without them.

…

A second faction, gathering in the Office of Security, proposed Demonic Interference.

"Not possession," a robed elder clarified carefully, his voice hushed to avoid invoking bad luck. "An anchor. Something bound without full manifestation. A void parasite using the boy as a doorframe."

I heard the shifting of weight in chairs. Unease.

"That would explain the refusal to resonate," the elder continued. "Sound requires a medium. The void has none."

"It would also imply exposure risk," a younger voice argued. "If he is a door, we must ensure it does not open. Why are we giving him tea? We should be giving him fire."

"Because if you burn the door," the elder hissed, "you might let in what stands behind it. Containment is justified. Observation is mandatory."

They see demons because they cannot imagine a silence that is not malicious.

…

A third faction, the pragmatists in the Registry, dismissed both.

"This is a broken mortal vessel," they argued. "A damaged foundation producing erratic results. His meridians are likely shattered in a way that creates a sinkhole effect. He is dangerous not because of power, but because of unpredictability. He is a structural flaw, not a weapon."

That explanation was the safest.

It required no cosmic implications. It required only isolation. It turned Wei from a monster or a god into a mistake.

They disagreed violently in private, politely in record. Their reports contradicted each other in tone, method, and conclusion. But they all ended the same way.

Subject should not circulate freely.

Consensus does not require understanding. It requires alignment of fear.

…

Night fell over the Annex. The filtered light in the garden faded, replaced by the soft glow of moss lanterns. The silence grew heavier.

Wei lay on the sleeping mat, staring at the ceiling. He had not touched the tea. He had not moved the pouch.

"Mistress?" he asked into the dark.

"I am here."

"If they decide I'm a demon," he said slowly, "will they kill me?"

"Yes."

"If they decide I'm a god?"

"They will enslave you."

"And if they decide I'm broken?"

"They will study you until you are gone."

He closed his eyes. The options were a triangle of doom.

"Then I have to be something else," he murmured.

"No," I corrected. "You have to be nothing. That is the only thing they cannot grasp."

He turned on his side, curling inward. He was trying to make himself small, trying to disappear into the neutrality of the room. But he didn't realise that his attempt to vanish only made him more visible to the System.

I watched the surveillance threads pulsing in the walls. They were weaving a net around him, tightening with every breath he took. They were measuring his sleep cycles, his heart rate, the displacement of air around his body.

They were looking for a pattern.

They would not find one.

And in their failure to find a pattern, they would eventually manufacture one.

That is the inevitable endpoint of bureaucracy. When the truth is illegible, they write a lie that is legible and call it justice.

I settled into the corner of the room, a shadow within a shadow. I would wait.

Let them argue. Let them draft their reports. Let them build their theories.

Please sign in to leave a comment.