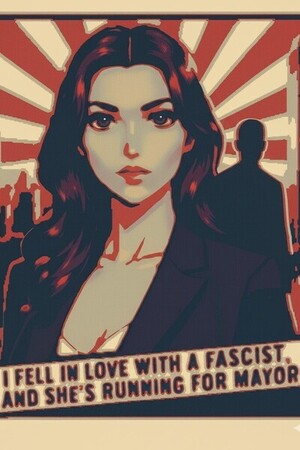

Chapter 19:

The First Date

I Fell in Love With a Fascist, and She’s Running for Mayor

The first date was platonic, but it lasted all night.

She had driven herself to the police station, in a tinted sports car no one would guess she’d drive. She drove me past the front of the police station, to show me the media frenzy I’d whipped up with my arrest and admonish me for it.

-I told you the media would be interested in you, just lie low for a little bit.

I promised her that I had been doing just that. I’d just been out for a walk, I hadn’t done anything to attract attention.

-Except be yourself, she laughed. Look, it’ll blow over, she continued.

The interest in me, she explained, would blow over once the trial for Blynken, Wynken and Nod started.

-Will you go visit them? She asked as she drove us out of the downtown area.

-I looked right into her eyes. I had the feeling she was testing me.

-I wouldn’t visit them, I began, even if it weren’t for all the media attention it would attract.

I looked out the window and noticed we were driving right past my own neighborhood and towards hers, a posh enclave on the outskirts of the ward that popped out really out of nowhere.

-You’ve got a funny way of showing me you like me, she said finally.

I just smiled at her and reached my hand out to put over hers, which she had resting on the gear selector even though the car was an automatic.

She smiled back at me.

-I’m going to call that photographer’s magazine in the morning and offer them a fluff piece if they drop it. You can pay for the camera right?

-I feel like everyone asks that. Who cares? Sure, I can.

-So, you like me? she asked as we got out of the car.

We made our way into her home. I wondered if anyone was watching.

I couldn’t believe it was happening. I don’t remember what I told her but I tried to explain how I felt. I know I called her a fascist a couple of times and she grimaced.

-Look, she finally said. You’re a pretty good looking guy, and you’ve got a fire in you, but you’re not very bright for all of that.

-I think I just find it hard to articulate myself when I’m with you, I blurted out.

-I don’t know that you make that much sense to other people either, she quipped.

We had settled down on the couch in the center of her spacious living room, it was in a kind of pit there. They used to call them conversation pits, I think, and it worked, because we ended up talking the entire night through. She had wine, too, lots of it.

We talked about politics a lot, and the presidential election then less than a year away. She was convinced the former president would win again, but I insisted there was no way a country would make the same mistake twice. She said simply that people, and voters especially, had short memories. She said she was more worried he’d waste away the second term the way she thought he’d wasted away the first.

-If he were half the fascist you took him for, she said, or that you took me for for that matter, it’d be a very different story. I don’t think anyone would like it. Fortunately, the truth is different. She paused as if she were considering something. Politics is messy.

I resisted the temptation to make a snide remark at how vacuous and tautological that was. Politics was messy.

We talked about our lives too. We’d both grown up in the city, and were just a few years apart in age. I was a senior at North High when she was a freshman at the magnet high school, Science & Art High. That would’ve made a big difference then but almost a quarter century later it doesn’t feel like much time.

Nevertheless, it put us in different circles. She told me how she went away to the small liberal arts women’s college in New England, intending to travel to Europe after graduating. She had been a Medieval Studies major. Her mother, who had died when she was six or seven, had instilled in her a big love for fairy tales and through that the history of where they came from. She wanted to travel to Italy.

But her father, a construction foreman who worked into his seventies, had fallen suddenly ill. Her father hadn’t taken it well when her mother dies. For months he didn’t say a word to her. He always had trouble, she said, trying to be a mom, but he did his best. And he never made her want for anything or required anything of her. She found out he was sick through a family friend.

She spent the next five years taking care of her father and using her degree to work at the library. When her father finally died, he’d left a lot more money behind than she imagined he had, given how meagerly he had lived outside of what he lavished on her.

With the money, she went to law school. Then the part of her biography that was public picked up.

She asked about my life. Both my parents were still alive. I never liked talking about my childhood but I tried to open up to her. The wine made it easier, and she seemed like she was listening without judging, letting me stumble through it.

At some point I fell asleep right there on the couch.

Please sign in to leave a comment.