Chapter 1:

Kalaallit Nunaat

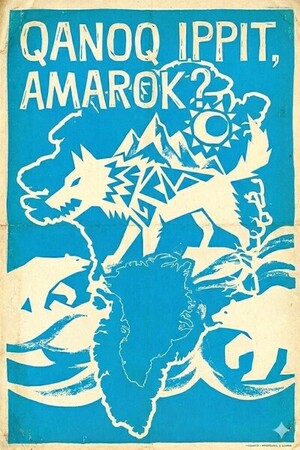

Qanoq Ippit, Amarok? (How Are You, Wolf?)

Not too long in the future, when the sea levels rise just enough to start opening up the sea around the Infglefield Fjord in early spring, just as the midnight sun rises for its four month journey across the Arctic skies above Qaanaaq, which older textbooks might have listed as Thule. Or New Thule, because back in the 1950s the Danish government moved all the villagers across the bay so that the United States could build an air force base. It’s where the Pittufik Space Base is now.

Not so long ago the population of Qaanaaq was plummeting, to fewer than 500, along with the rest of Greenland. Not so anymore, with gold diggers, literal and metaphorical, getting through from all across the world.

Qaanaaq was still difficult to get to, and Leffer Cliff wasn’t looking forward to going there, but his bosses had come to the unfortunate conclusion that there was no other way to figure out what exactly was going on up there in Qaanaaq.

The company had bought several thousand acres during one of the government’s flash sales of speculative land in Greenland. They were parcels the warmer weather had made accessible for the first time, but there was no infrastructure to get there and no guarantee of any minerals.

Nevertheless, the company had gotten the idea that these particular parcels outside of Qaanaaq might have deposits of uranium, and at the very least they ought to be rich with iron. The parcels also gave them the permission to open up an office in Qaanaaq, and the company had had an eye on entering the tourism trade. A lot of people wanted to go to Greenland now, to see the midnight sun while the polar caps melted. Tourism made about as much sense for a cookie company as mineral extraction. It all started when the company realized it needed to secure its own vast water supply to maintain the production of cookies in all the varieties it had introduced in its drive for more global market cap.

Leffer Cliff was a fixer. He’d worked for the company since flunking out from Navy Seals boot camp, or so he said. His colleagues, such as they were, suspected something worse than what he’d casually admit to. He’d been deployed in the Midwest U.S. to secure water pipelines from tribal unrest, to West Africa to secure cocoa fields from religious extremists and even once to a Western European country we won’t mention when it had some electoral discrepancies that could’ve cost the company a lot of money if they got reversed.

Leffer was on his way to Qaanaaq because the last two teams of fixers had disappeared, and the company could not get an answer, or even in communication with, anyone they’d dealt with in Qaanaaq. The government wasn’t helpful either—their obligation ended with the sale of the parcel, as far as they were concerned.

Leffer got into Nuuk on a Monday night flight from Newark, no problem. The weather was good and they made it in four hours. It was a domestic American flight and no one spoke Kaalallisut, or Greenlandic. Kaalallisut is a good word, it’s what the language sounds like.

Leffer had gotten an earful of it listening to a radio station from Greenland he had pulled up after his bosses told him he’d be headed there. He liked to listen to local radio to get a sense of the feel of a place, through its sound. He’d done the reading too. The parcels were about a hundred kilometers inland, and even with the warmer weather there wasn’t a trail there. The company’s teams had been equipped with snowmobiles and settlement-in-a-box gear. There were two theories, that they’d hit bad weather and died, or that they absconded with the company property to go off on their own in Greenland. The latter was a minority view but the minority felt strongly about it. It had been happening more often with company assets across the world. The board of directors had even recently approved a ten percent increase in spending on asset recovery for these kinds of situations. It’s how Leffer was getting paid.

Leffer was not of the minority view. He’d read the dossiers on the teams that went up to Qaanaaq. Good men and women, veterans of the Arctic war with science backgrounds, the kind of human capital the company was short on. It was far more likely, Leffer thought, that something happened.

The trip from Nuuk to Qaanaaq was a lot more difficult. On paper it was only supposed to be half an hour to forty five minutes longer, but it ended up taking a lot longer. First, the flight was delayed because of too much ice on the wings. You’d think climate change would have solved those kinds of problems, Leffer thought disdainfully. When they finally got into the air, they hit turbulence immediately. The winds, the pilot announced, would be against them most of the way. They flew west out of the flight path to get away from it, but it only made the trip that much longer. Once they got above the airport, they circled it for hours, until the fuel was almost gone, before getting the all clear to land. It was never explained what the issue was, beyond a “hazard on the runway.”

Leffer had gotten in to Nuuk too early to eat, and had now arrived in Qaanaaq too late to eat. He needed coffee at least, and found a custodian mopping around the luggage carousel who he convinced to pour him a cup of coffee from the employee break room.

It was the worst cup of coffee he ever had.

Please sign in to leave a comment.