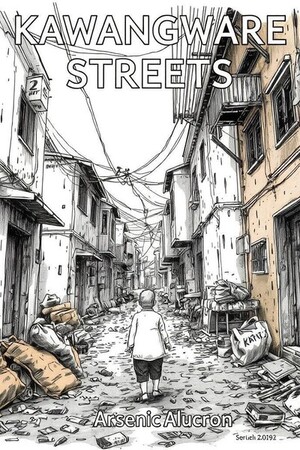

Chapter 21:

THE TALE OF EAZY

KAWANGWARE STREETS

The sun burned hot over Eastlands, making the corrugated roofs shimmer like molten steel. Ezekiel Mwazi adjusted his tie, already sweating through his shirt, while Frances dragged him by the hand toward the squat concrete block of Baraka Health Centre.

“Hurry up, Ezekiel,” she hissed. “We’re fucking late!”

He jogged to match her pace, holding tight to his small leather satchel — the same one he had carried since their final year in medical school. It still smelled of old paper and ink. He had dreamed of this day for years: their first posting, their first job as residents, their first step into a life of healing.

Gazing at the gate, they released their joined hands. Not because it was against the rules to date. Nope. No one cared about that here. It was because of the reality check they got after seeing what was on the other side of the gate.

Ten long wooden benches lined the courtyard, every single one overflowing with patients. Mothers with babies strapped to their backs. Old men hunched over canes. Children coughing until their tiny ribs rattled. The smell of sweat, dust, and despair clung to the air.

Inside, a voice thundered like a whip:

“NEXXXT! MOVE! I SAID MOVE!”

It belonged to a bald man, thickset, dark-skinned, with teeth stained the color of turmeric. He shoved a patient’s file into a nurse’s hand and spun around. His eyes landed on Ezekiel and Frances, narrowing like blades.

“You there,” he barked, pointing. “What’s your ticket number?”

Ezekiel blinked looking at Frances. “Uh—”

SLAP! The man’s palm cracked across his shoulder, shoving him back a step. “I said what’s your ticket number? You deaf?”

Frances stepped in. “We’re not patients. My name is Francesca Muthoni, and this is Ezekiel Mwazi. We’re the new residents assigned here.”

She extended her hand. The bald man ignored it, his lips curling.

“So you’re the Pyamu, huh?”

“The what?” Ezekiel asked.

“What? You don’t know Sheng’,” the man grunted. “Means fresh meat. You freaking kids all think you’re better than us, huh?”

He jabbed a finger toward the back corridor where a row of cracked plastic chairs sat beneath a flickering fluorescent bulb. “Got sit there. Watch. Learn. Don’t talk unless spoken to.”

Ezekiel and Frances obeyed, sliding into the corner like schoolchildren.

They waited. And waited. Patients streamed in and out, cries echoing through the thin walls. The bald man — whose name they would later learn was Dr. Bwana — barked orders all day, a tyrant in a dirty white coat. Ezekiel’s fingers itched to help, but no one called them.

Hours dragged by. Eight a.m. became noon. Noon melted into dusk. Frances paced around in a straight line. Ezekiel remained calm, watching the patients. The benches outside emptied, filled, and emptied again. By the time the last patient shuffled out, it was nearly ten at night.

Dr. Bwana strolled past, whistling. He stopped when he saw them still sitting. “Huh. You’re still here?”

“Yes,” Ezekiel said, standing. “No one ever called our names. We’ve been here since morning. What gives?”

Dr. Bwana tilted his head. “What gives? What the hell does that mean?”

“You said we’d be oriented,” Frances snapped. “Instead you wasted our entire day.”

“Oooh, listen to the Pyamus,” he sneered. “Big man, big woman. You think the world stops for you?” He stepped close, his breath sour with cigarette smoke. “Two things you need to learn fast. One: nobody has time for your feelings. Two: you follow instructions. I told you to observe. So tell me, what did you observe?”

Ezekiel clenched his jaw. His mind replayed the day in fragments — the endless line of patients, the lack of supplies, the handful of exhausted doctors drowning in the flood.

“There were too many patients,” he said finally. “And only five doctors to treat them. It’s not sustainable.

Dr. Bwana grinned, showing his yellow teeth. “Good. You’re not as useless as you look. That’s your lesson for today.” He tapped Ezekiel’s chest with a thick finger.

“Everyone who walks through that gate waits like everyone else. Even you. You think you’re special?” He turned to Frances. “You think your fancy grades matter here? This is Eastlands, si Karen.”

Frances inhaled sharply but held her ground.

Bwana snorted. “Tomorrow, be here at six. Not six-oh-one. Six. Be ready to bleed for this place, just like the rest of us.”

He turned and walked away, humming again, leaving them in the dim corridor lit by the dying bulb.

Ezekiel let out a breath he didn’t realize he’d been holding.

“You okay?” Frances asked.

“No,” he said honestly. “But I will be.”

She gave him a tired smile. “Come on. Let’s get out of here.”

Frances grabbed his hand, her eyes fierce.

“Don’t let that man break you, Ezekiel,” she whispered. “We’ll make this broken system work for us…just wait and see. We can still make a difference. We have to.”

They walked out together into the night air — thick, smoky, buzzing with distant matatus and shouting street vendors. Their hands brushed, then interlocked, not caring who saw anymore.

Ezekiel looked back once at the rusting gates of Baraka Health Centre.

Tomorrow, he knew, would either break him…

…or forge him.

Either way, there was no turning back.

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

The next morning came too fast.

Frances and Ezekiel walked through the gate at 5:58 a.m., determined.

Dr. Bwana barely looked up from the file he was scribbling in.

“Ah. The Pyamus return.”

Dr. Bwana who they actually learned was the head doctor. He used to work for a national hospital until he was fired because of his “personality problems”. Now he works where he believes is beneath him and he makes sure everyone knows this.

Frances and Eazy exchanged a glance — a language only they understood, a tension of exhaustion and silent defiance.

Bwana snapped his fingers at them. “Hey! If you two want to talk in Morse code, go do it outside. This is a hospital. My hospital. When I ask a question, you answer. What’s wrong with this Patient?”

He pointed at an elderly woman trembling on the examination bed.

Eazy stepped forward, but she didn’t look sick — she looked scared.

Scared of Bwana.

Her eyes kept darting toward him like he was a threat.

Eazy’s throat tightened.

Bwana cut him off. “Why is she shaking? Hmm?”

He leaned over Ezekiel’s shoulder. “Because she knows if she doesn’t stop wasting my time, I’ll throw her out.”

This wasn’t medicine.

This was intimidation.

Dr. Bwana’s laughter faded into the dark hallway, leaving Frances and Ezekiel alone in the humming silence of Baraka Health Centre. The buzzing fluorescent bulb above them flickered in irregular spasms, as if even the electricity was exhausted.

Frances inhaled sharply, biting back a retort.

The rest of the shift was a blur.

Long lines.

Crying children.

Coughing elders.

No oxygen, no antibiotics, barely any bandages.

Frances swore under her breath after every patient.

“We studied six years for this? Six years for aspirin and prayers? This system isn’t broken, Ezekiel — it’s rigged!”

Eazy exhaled slowly, shoulders sagging.

“That guy…” he muttered. “How does anyone work under someone like that?”

She took his hand.

“That’s the reality of Baraka, Ezekiel. Understaffed. Undersupplied. Undervalued.” She squeezed his fingers. “But we didn’t come here for him. We came for the people out there.”

She gestured toward the courtyard where the last stragglers were limping home beneath the rusty streetlights.

“They are why we’ll survive this place,” she added. Voice low, “And once we do that, we’ll be able to handle any hospital in the country and help out everyone. Who knows we could even find the cure for cancer.”

Eazy managed a tired smile. “You’re insane.”

“Yeah,” she said proudly. “But you love me for it.”

They walked out together.

The moon hung low over Eastlands, pale and swollen, washing the dusty road in silver. Street vendors were already packing up, scraping the last bits of chapati dough from metal pans. A group of schoolboys kicked a flat football down the road. A boda-boda rattled past, headlights flickering like dying fireflies.

Frances wrapped her arm around Ezekiel and laid her head lightly against his shoulder.

“You okay?” she asked.

He hesitated, then nodded. “Yeah. Just… overwhelmed. First day and I didn’t help a single patient.”

“You will,” she said. “Tomorrow will be different, you’ll see. I heard supplies are coming, oxygen and antibiotics up the wazoo.”

“It better be,” he whispered. “I didn’t become a doctor to watch people die.”

“You didn’t become a doctor to be easy either,” she teased. “See me, I got to work with two lovely young girls today that had the sniffles. It was awesome and all because I wouldn’t take no for an answer. Dr. Bwana tried to set me to the side and I wouldn’t have that shit. You can do it too, just stop being so nice.”

He laughed softly. “So I’m easy now.”

“Don’t pout, you know what I meant, Eazy. That’s my new nickname for you now.”

Please sign in to leave a comment.