Chapter 1:

CHAPTER 1: GRAY MORNING

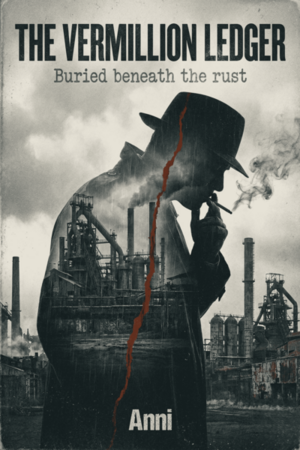

The Vermilion Ledger

The coffee was cold by the time Detective Thomas Mercer noticed it. That was the thing about whiskey the night before—it didn't just poison you; it made you stupid the next morning. Slow. Unreliable. He stared at the cup on his desk like it was a personal insult.

The precinct smelled like it always did: stale cigarette smoke, burnt coffee, and the accumulated sweat of men who'd stopped trying. The fluorescent lights hummed with the mechanical indifference of a machine that had forgotten it was supposed to help people. 7:47 AM on a Tuesday, November 1975. Gray outside the windows. Gray inside. Gray everywhere, as if the city had been drained of color and left to rot.

Mercer was forty-four years old and looked fifty. The divorce had aged him in ways a mirror couldn't quite capture—something in the eyes, a hollowness that had nothing to do with sleep. His ex-wife Margaret had taken their daughter Sarah with her to her mother's house in Connecticut, which was fine by Mercer. Better, even. Kids needed stability, and Mercer was a lot of things—a decent cop once, a competent investigator, a man with a job—but stable wasn't one of them anymore.

He lit a cigarette without thinking about it. The pack was almost empty. He'd need to buy more on the way home, though he had no home, just an apartment that smelled like old takeout containers and regret.

"Mercer." The voice came from behind him, attached to a body that was too young and too clean for this precinct. Detective Sarah Chen, thirty-one years old, three years on the force, still had that look of someone who believed the job meant something. She was holding a file folder like it contained secrets. In this precinct, maybe it did.

Mercer didn't turn around. "Don't tell me."

"Kid. Eight years old. Found in the old Riverside warehouse on Calhoun Street about two hours ago." Chen came around his desk and put the folder down. "A maintenance worker found him. Called it in at 5:15."

Mercer took a drag on his cigarette. The smoke curled up toward the ceiling in lazy spirals, like it had nowhere to be. "Where?"

"Warehouse. Like I said."

"In the warehouse? Under something? What?"

"On the floor." Chen's voice was careful, professional. She was still learning to deliver bad news without flinching. "Positioned on a tarp. Clean. Almost respectfully arranged."

That made Mercer look at her. Respectfully arranged didn't fit with most child murders. Most child murders were frenzied, panicked, sloppy—the work of drunk stepfathers or meth-addled boyfriends who snapped. This sounded different.

"Name?" he asked.

"David Chen. No relation." She paused. "Nine-year-old. Shit, I said eight. I don't know yet. There's a notation on the file. He was reported missing three days ago, but the call got logged wrong, filed under runaways. Nobody connected it to a missing persons until the body turned up."

Mercer closed his eyes for a moment. Three days between missing and found. That was time. That was an opportunity for the system to actually work, and the system had failed before it even got started.

"Photos?" he asked.

"At the scene. Photographer's still there. Captain Hawkins wants you to take it. Said to move fast on this one. Media's already picking it up."

That made sense. Media moved fast on child cases. It made people afraid, and afraid people sold papers. Hawkins would want the case closed quickly—or at least appear to be closing quickly. Politics and optics mattered more than solutions.

Mercer grabbed his coat. It was the same coat he'd been wearing for three years, brown wool, stained at the cuff, smelling vaguely of cigarette smoke and failure. "What precinct was the missing persons filed in?"

"South side. Different jurisdiction. Different shift. Different everything."

"Of course." Mercer stood, stubbed out his cigarette in an ashtray that hadn't been emptied in a week. "Let's go look at a dead kid."

They drove in Mercer's car, a 1972 Buick that had seen better days and was currently experiencing its worst ones. The heater only worked on the passenger side, a situation that Chen didn't comment on but that made Mercer angry every time he thought about it. The city rolled past the windows in shades of gray and brown—brick buildings, empty lots, the skeletal remains of factories that had shut down years ago. This had been a steel city once, a place where things were made, where there was pride and purpose. Now it was just the memory of that, a ghost town that hadn't yet realized it was dead.

"Did you know him?" Chen asked as they drove. "The kid?"

"No."

"I mean, did you have any interaction with the family? Before?"

Mercer kept his eyes on the road. "No. Why?"

"Just asking. Sometimes with kids, there's a connection. Family you've dealt with before. Domestic issues."

"Not this one," Mercer said. He didn't add anything else. Chen was still at that stage where she thought each case was a puzzle with a solution, a problem with an answer. She'd learn differently soon enough.

The warehouse was one of dozens that occupied the industrial corridor east of downtown. Massive structures of brick and broken windows, relics of the city's prosperity now used for storage, if they were used for anything at all. Police cars were already there, their lights flashing red and blue against the gray morning, painting everything in colors that meant nothing.

A uniformed officer was standing at the entrance to the building, looking like he wished he was anywhere else. He checked their badges without really looking at them and waved them inside.

The body was in the basement. Of course it was. Basements held secrets in cities like this—places where things could happen undisturbed, where screams wouldn't be heard, where a child could be left alone with whatever terrible thing had decided to take him.

The photographer was already there, snapping pictures with the mechanical precision of someone who'd documented a hundred crime scenes and was trying very hard not to think about any of them. The body was on a blue tarp, positioned on its back, arms at its sides. The child's face was pale, almost luminescent in the harsh light of the photographer's flash. His eyes were closed. He looked peaceful, which was the sickest thing about it.

"No visible trauma," the photographer said without being asked. "No signs of abuse, beating, anything like that. Clothes intact. Clean. It's like—" He paused, searching for the word. "It's like he was prepared."

Chen knelt down to look at the body more closely. Mercer stayed back, observing the scene with the detached eye of a man who'd stopped believing that any of this mattered. The basement was cold and damp, the kind of place that smelled like rust and old concrete. A single bare bulb hung from the ceiling, casting harsh shadows.

"Cause of death?" Mercer asked.

"Won't know until the autopsy," the photographer said. "No obvious signs though. No ligature marks, no blunt force trauma. Could be asphyxiation, could be poisoning, could be a hundred things."

Mercer looked at the child's face again. Peaceful. Respectfully arranged. That word kept coming back. Most murderers didn't respect their victims. They used them up and threw them away. This was different.

"We need to talk to the parents," Chen said. She was professional, focused. "We need to know where the kid was last seen, what he was doing, who he was with."

"Yeah," Mercer said. "We do."

The Chen family lived in a small row house in a neighborhood where the houses pressed up against each other like they were trying to share warmth. It was ten in the morning, and the street was mostly empty. Most people were at work. The ones who weren't looked like they wished they were.

Mrs. Chen opened the door before they knocked. She was small, thin, with dark hair pulled back tightly and eyes that had the look of someone who hadn't slept in days. She knew why they were here. People always knew.

"Mrs. Chen?" Chen asked gently.

The woman nodded. She didn't move to let them in. She just stood there, gripping the door frame like it was the only thing keeping her upright.

"I'm Detective Chen. This is Detective Mercer. May we come inside?"

It took Mrs. Chen a moment to process this. Then she stepped back, and they entered a living room that was small and neat and filled with the kind of careful order that people maintained when they were trying very hard not to fall apart. Photographs on the walls. A school picture of David, smiling, his hair neatly combed. He looked like a normal kid. He looked like he should still be alive.

"We found David," Chen said. She wasn't using past tense yet, just stating facts. That would come later. "He was found this morning in a warehouse on Calhoun Street. I'm very sorry."

Mrs. Chen made a sound that wasn't quite words. It was the sound of something breaking internally, the vocal manifestation of a catastrophe that had been waiting to happen since David went missing three days ago. She sat down on the couch without appearing to make the decision to do so, simply collapsing into it like her legs had given up.

"When did you last see David?" Mercer asked. His voice was flat, professional. He wasn't being cruel; he was just being practical. Information was information, and they needed it.

Mrs. Chen stared at her hands. "Monday morning. He went to school. Lincoln Elementary. I packed his lunch. A sandwich and an apple. He liked apples." She paused, as if the fact that her son had liked apples was somehow important, some detail that could still matter in a world where her son was now dead on a tarp in a basement.

"Did he come home from school?" Chen asked.

"No. I called the school at three o'clock. They said he wasn't in class that afternoon. They said he'd left during lunch. They said..." Mrs. Chen's voice cracked. "They said he just walked out. No one stopped him. No one was watching."

Mercer and Chen exchanged a glance. A eight-year-old kid walks out of school in the middle of the day, and nobody stops him. Nobody calls his parents. The system working as designed.

"Was David having any problems?" Chen asked. "School problems? Family problems?"

"No. He was a good boy. Smart. He liked to read. He wasn't the kind of kid who..." Mrs. Chen trailed off. She wasn't the kind of kid who what? Got kidnapped and killed? Got left on a tarp in a basement? The sentence couldn't be completed because the premise was impossible.

Mercer moved to the window and looked out at the street. A woman was pushing a stroller down the sidewalk. A man was standing on a corner, smoking a cigarette, waiting for something. The city continued. People continued. David Chen didn't.

"We'll need to talk to your husband," Chen said.

"He's at work. I can call him."

"Please do."

Mercer watched the street and smoked a cigarette and tried very hard not to feel anything about the small school picture on the wall or the woman on the couch who was now making phone calls with a voice that sounded like it belonged to someone else's body.

Back at the precinct, Mercer filed the initial report and checked the missing persons file that had been misfiled three days ago. The officer who'd logged it was named Daniels, a patrol cop who'd been on the force for eight years and had apparently learned nothing in that time about attention to detail. When Mercer found him in the break room, Daniels was eating a sandwich and reading the sports section.

"Daniels," Mercer said. "You logged the Chen missing persons report Monday afternoon?"

Daniels looked up, his jaw working on turkey and cheese. He was fat, going soft in the middle, the kind of cop who was counting down the days to retirement and not counting fast enough. "Yeah. What about it?"

"You filed it under runaways."

"Kid was eight. Sometimes they run. Usually they come back."

"Except this one didn't come back. He got killed. He's been found dead in a warehouse, and we lost three days because you filed the report wrong."

Daniels set down his sandwich. His face reddened. "I did the paperwork the same way I always do it. Not my fault if the system sucks."

Mercer wanted to hit him. It was a clean, clear desire, the kind of thing he'd learned to recognize and compartmentalize in his years as a cop. He turned around and walked away instead, which was probably the better choice but didn't feel as good.

Chen was at her desk, already making calls. She was trying to establish a timeline, to figure out where David Chen had gone after he left school. Interviews with classmates, with teachers, with the crossing guard who may or may not have seen him. The work was methodical and probably futile. By the time they established a timeline, the trail would be cold.

Captain Hawkins came out of his office around noon. He was a tall man going gray, with the carefully maintained appearance of someone whose career was important and who was protecting that career with every decision he made. He'd been a cop once, but somewhere along the way he'd become a politician.

"Where are we on the Chen case?" he asked, already knowing that they were nowhere, that progress was impossible, that everything was already failed.

"Early stages," Chen said. "We're establishing timeline, talking to people who saw him. Autopsy's scheduled for this afternoon."

"Media's going to want statements," Hawkins said. "They're already asking. I'm going to tell them we're treating this as an active investigation, that we have leads, that we're pursuing all angles. That sort of thing. I need you two to make it true."

"We will," Chen said. She said it like she believed it, like effort and intention could change the fundamental indifference of a city where children could walk out of school and disappear.

Mercer didn't say anything. He was already thinking about the autopsy, about what they'd find when they opened up David Chen and looked inside. Probably nothing that would help. Probably just the mechanics of death, the boring biological facts of how a small human body stopped functioning.

The autopsy was at three in the afternoon. The medical examiner was a man named Garrett, in his fifties, with the demeanor of someone who'd examined thousands of corpses and had become philosophically resigned to the fact that all living things eventually became dead things.

"Asphyxiation," he said, pointing at the bruising on the inside of David Chen's throat. "Manual strangulation. Quick and efficient. He probably didn't suffer much, if that matters."

It didn't matter. Dead was dead, and the fact that he hadn't suffered much was not a comfort to anyone.

"Toxicology?" Chen asked.

"Nothing unusual. No drugs, no poison. Just a kid who was strangled by someone with enough strength and enough knowledge to do it without leaving obvious marks. Whoever did this knew what they were doing."

That word—knew—hung in the air. Not a crime of passion, then. Not a panicked act. Something deliberate. Something planned.

"Time of death?" Mercer asked.

"Best estimate, Monday evening. Maybe late afternoon, maybe early evening. The body's been cooling, but not much. He was moved post-mortem, kept somewhere cold. The warehouse was cold, that would preserve him."

Chen was writing notes. Mercer was thinking about the tarp, the respectful arrangement, the careful positioning. He was thinking about the kind of person who could strangle a child and then arrange his body like something precious.

"Anything else?" Chen asked.

"Not that I can tell. Healthy kid otherwise. Good nutrition, no prior injuries, no signs of abuse. This was the first time anyone hurt him, and the first time was also the last."

They left the autopsy suite and stood in the hallway outside the medical examiner's office. The fluorescent lights were the same harsh white as everywhere else. The world was made of these lights now, Mercer thought. Harsh and cruel and illuminating nothing that mattered.

"We need to find where he was kept between Monday afternoon and Tuesday morning," Chen said. "We need to talk to more people. We need—"

"We need to catch a murderer," Mercer said. His voice was flat. "And we won't. We'll look, and we'll follow leads, and we'll file reports, and we'll eventually move on to the next case. And David Chen will be filed away in a cabinet somewhere, and someone will remember him sometimes, and that will be it."

Chen looked at him. "You don't know that."

"I know it," Mercer said. "I've seen it a hundred times. I've done it a hundred times. We're not the heroes here. We're just the people who show up and take notes and pretend it matters."

"It matters," Chen said.

Mercer didn't argue. He just walked away, heading back to the precinct to file paperwork and make calls that would lead nowhere, to do the work of being a detective in a city that had stopped caring about dead children and had probably never cared very much in the first place.

The sun was setting by the time he left the precinct. Gray light turning purple, turning black. He drove to a bar on the east side, a place called Murphy's, and ordered a bourbon. The bartender knew him, knew his usual order, knew not to try to engage him in conversation. Mercer drank slowly, watching the other patrons—men mostly, men without jobs or homes or reasons to be anywhere else. They looked at nothing and thought about nothing and existed in the quiet desperation of people who'd stopped believing in change.

He thought about David Chen on the tarp. He thought about the mother's hands. He thought about the school picture on the wall and the sandwich that had been packed with an apple. He thought about a child walking out of school in the middle of the day, trusting or stupid or desperate in a way that only a child could be.

Then he pushed the thoughts away, finished his drink, and drove home to his apartment where he would drink more and sleep poorly and wake up tomorrow to do it all over again.

The city was gray. The future was gray. Everything was gray, and Mercer had stopped noticing the color years ago.

Please sign in to leave a comment.