Chapter 7:

EPILOGUE I: 3 Years Later

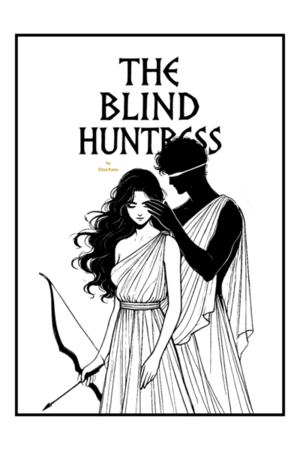

The Blind Huntress (short light novel)

EPILOGUE I

ΤΡΙΑ ΕΤΗ ΥΣΤΕΡΟΝ

3 Years Later

LATE AUTUMN, 411 B.C.E.

Mēlesía learned quickly that wealth meant nothing without knowledge.

In Dodona, a merchant had cheated her almost immediately. He dismissed her carnelian as flawed and offered far less than it was worth. She didn’t argue—but she remembered everything.

She continued south, toward Ambrakia, where metals and dyes were exchanged for livestock, tools, and grain. There, she began to observe—not just the goods, but the people who traded them. She listened more than she spoke, watching how tone, timing, and body language could shift the terms of a deal.

To survive in markets ruled by men, she adapted every part of herself—her voice, her posture, even how she stood when approached. She dressed simply, bound her hair, and lowered her gaze when needed. She often made herself appear older or poorer than she was.

When it felt too dangerous to speak directly, she sent others to act in her place. Sometimes it was a boy paid with bread and a coin, or an old man whose beard earned trust. Sometimes it was a widow who owed her a favor, or a trader passing through who didn’t ask questions.

At times, she bought the appearance of male authority by offering a cut of the trade—like a fisherman in Argos, or a cloth-seller’s nephew in Elis—they spoke on her behalf when being a woman would have cost her the deal.

She never gave her real name.

It was the only way to move without drawing attention.

To Mēlesía, this wasn’t deception. It was how she stayed alive.

A woman traveling alone, carrying rare stones and gambling rarer plans ... as she was, couldn’t afford to be remembered.

⁂

At first, Mēlesía made more mistakes.

A merchant in Kassope swore that her onyx was too dull for carving—only for her to later see it polished into a signet ring on the hand of a magistrate.

Another in Amphilochia laughed outright at the price she set for lapis.

Another in Stratos pressed a warm smile into her palm along with a handful of bronze obols, assuring her they were fair payment for her amber—only for her to later find that half the coins were clipped, their edges shaved thin.

By the end of her first season, with war clogging the roads, she’d learned to keep her face blank, lie without blinking, and even let men walk away thinking they’d won.

She was never comfortable, never settled.

⁂

She survived on hunting.

She set small traps near the riverbanks, snaring hares and game birds when luck was on her side.

When she traveled, she followed the land, pulling wild onions from the earth, gathering bitter greens, boiling them in clay pots when she had the luxury of fire.

In towns, she bartered for food only when necessary, knowing that coin drew more eyes than quiet labor ever would.

She worked where she could, moving from village to village with the ease of a traveler.

She slept where she could—beneath temple eaves where priests fed the weary, in stables among the warmth of cattle, beneath the open sky with only her cloak to shield her from the wind.

At potters’ yards, she hauled heavy clay, sweeping dust from kiln floors until her arms ached.

In dye houses, she stirred vats of indigo and woad, the color staining her fingers long after she had left.

Near the coast, she carried baskets of fish for Phoenician traders, listening as they spoke of distant lands, of merchants willing to pay well for the very stones she carried.

She was learning.

More than that—she was alive.

WINTER, 410 B.C.E.

By winter, she no longer traded the precious stones directly.

Instead, she sought out artisans—men who cut amulets and carved rings, women who knew which households still had silver to spare. They worked quietly, often from the backs of shops or shaded corners of market stalls, and asked fewer questions than merchants.

During the harsher months, when work grew scarce and roads more dangerous, she spent the stones sparingly.

A single polished amethyst paid for a week’s stay in Argos, where a widow offered her a pallet near the hearth and a bowl of lentils each night.

A sliver of quartz bought her passage south with a group of shepherds—a large enough group to keep bandits at bay.

As she traded across the region, she quietly redirected goods back toward her village—better grain, sturdier tools, livestock, cloth…

All the while, she made sure her wealth found its way to her father.

In select deliveries, one item was always set aside for a location known only to Mēlesía as her father’s home. A bundle of barley, a new plow head, or a sharpened blade—always something useful, never lavish, and small enough to pass unnoticed. The item would be slipped into a larger shipment bound for her village, handed off to a porter who needed no explanation, or given to a trader who would accidentally drop it nearby. Sometimes it was left at the edge of her father’s field, other times at the threshold of the house—spilled, misplaced, or tossed carelessly as if it had come loose in transit.

Each drop was carefully planned. Never too valuable. Never too often. Never in a way that might raise suspicion.

By the time a full year had passed, Mēlesía had begun to wonder if belief itself had become stronger than truth.

EARLY SPRING, 409 B.C.E.

Mēlesía continued to send her wealth ahead—hidden in the hands of those who never knew they carried it.

A Phoenician trader, believing he hauled nothing more than dyed cloth, unknowingly bore iron tools into Epirus.

A Thessalian herdsman, paid in advance, led a small flock of goats toward her homeland.

A merchant from Ambrakia sold grain at a generous rate—not out of kindness, but because her village had quietly become worth the investment.

As spring returned completely, the obol of love gifted to her by Nýxios, hidden in the deepest fold of her belt, tucked beneath the wrapping layers of her chiton, kept slipping free.

It shouldn’t have.

She had reinforced the stitching, re-knotted the seam, re-wrapped the layers by firelight more than once.

Still, the obol of love always found its way free—warm against her thigh, dropping toward the hem, or fallen onto the grass—appearing exactly where it shouldn’t have been.

Each time it moved, she adjusted—her body reacting before her mind could catch up.

No matter how she secured it, the result remained the same: it kept falling free, and she kept falling to catch it.

She remembered the first time it had truly startled her—outside Leukas, helping a woman bundle flax near the roadside in the morning, when the fog was thick. The obol of love slipped from her belt, hit her hip hard, and fell to the ground. She stepped back to catch it as usual—only then realizing a runaway ox-cart had thundered past the exact spot she’d been standing, close enough to shatter her ribs.

Later, in the crowded lanes of Patrai, she’d squeezed between two burly, drunk merchants mid-argument. As she passed, the obol of love shifted again—this time slipping completely free, clinking against her thigh and falling to the dirt. She knelt to recover it, and in that same moment, a dagger flew across the path above her head—hurled in blind fury by one of the drunk merchants.

Near Antikyra, at the edge of a riverbank, when she knelt to draw water, the obol of love had rolled loose once more, grazing her skin as it dropped. Her hand moved to grab it without thinking. At the same time, a silver-coiled snake burst from the stream, jaws wide, fangs cutting the air where her arm had been.

She thought nothing of it then.

Only now, looking back, did she recognize the pattern.

Had he been with her then, too?

LATE AUTUMN, 408 B.C.E.

Mēlesía’s home village, Perisykē, lay ahead, nestled quietly in the hills of Epirus.

From where she stood, hidden among the olive trees and dressed in the rags of a beggar, she could just make out the narrow path curling past the old grain store, and the thin line of smoke rising from the village hearth.

She hadn't come to speak, nor to reveal herself. She didn’t need to tell them what she had done. That wasn’t the reason she returned. She came only to see if the work she had set in motion had held—and if it hadn't, to learn what needed changing.

Keeping to a quieter route, she slipped into Perisykē unnoticed.

As she walked, she watched carefully—taking note of the sharper plows catching light in the fields, the granaries filled to the brim, the herds of goats she didn’t remember from before.

The signs were small, but visible.

The fields that once struggled now produced more. The soil had healed, yes, but more than that, the tools were better and the hands working them had grown stronger.

Granaries that had stood half-empty now brimmed with enough to last through two winters.

She traveled along the edge of an olive grove until her family home came into view.

Her father sat at the threshold, wrapped in a thick wool cloak, on the same worn chair he once carved by hand. His shoulders were hunched, his hands still in his lap. He gazed out across the yard, unaware she stood in the trees only a few acres behind him. He gazed out across the yard, unaware that she stood hidden among the trees just a few acres behind him.

She watched him for a long while.

He was thinner than she remembered. The lines on his face had deepened.

In her absence, Mēlesía had found ways to send him letters—short messages on scraps of linen, bark, or fig leaf, tucked into merchant sacks or hidden between wax tablets.

Her messages were never signed, never addressed, but she hoped the words were enough. Enough to tell him she was alive. That she hadn’t left out of carelessness, but from fear—fear that if she tried to say goodbye, she might not have left at all.

She had told him that she was safe; that she had found work, and that she would return soon.

She never knew if the messages reached him. Still, she sent them.

War had touched everything.

To most, Perisykē had no value. It was just another weather-worn, hillside village.

Epirus, though officially neutral, sat between powerful, watchful states.

Suspicion followed lone travelers, especially those who moved freely across borders or spoke with accents that didn’t quite belong.

Letters were opened. Markets were watched.

A woman without a household, trading alone, was easily mistaken for a courier—or worse, a spy.

Mēlesía understood the risk of sending letters.

If any message had been traced back to her—or worse, to him—her father could have been accused of sheltering a traitor. Punishment was never subtle: property confiscated, exile, public flogging, forced labor.

In times like these, even an act of care could be condemned as a crime.

Now, beneath her worn cloak, her chilled hands curled inward, pressing lightly against her ribs.

The urge to step out of hiding, to call him father, pulled at her.

She forced herself to stay back.

She had not come back to be a daughter.

She was a huntress, here to confirm her marks.

Only this once, here to measure the weight of her work as a ghost, to see whether the quiet projects she had set in motion had taken root, or not. She needed to know if the hands and feet she had hired were still loyal ... and if they had survived without her.

Now, she knew.

She had seen it with her own two eyes.

Without a word, Mēlesía turned and walked away.

What she had seen told her one thing: her work was not finished.

Please sign in to leave a comment.