Chapter 8:

The Weight of Victory

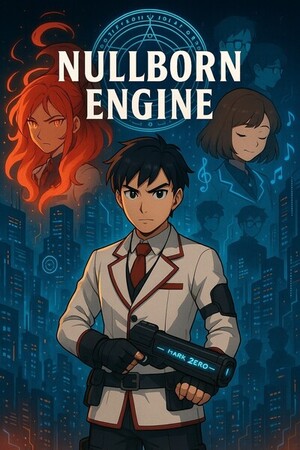

Nullborn Engine

Seiryoku felt louder after a spectacle. Not louder in sound alone—the city-campus never truly had silence—but louder in attention, like a room that had been turned to face one corner and would not stop staring.

Someone had decorated the courtyard with glittering illusions the night after the midterms. Koi-shaped sigils leapt from students’ notebooks and wrapped the fountains in shimmering scales. Fireworks of minor spells popped above snack stalls. Lanterns along the walkways pulsed in sync like a heartbeat that wanted an audience. The wards over the classroom arches hummed their usual protective notes, but now they seemed to pulse in curiosity.

And then there was me.

I could have tried to be invisible and probably failed at it like the rest of my life had trained me for. Instead I kept my head down and my bandaged hand wrapped in a sleeve where possible. The official scar-trace of the last duel mapped a pale crescent across my palm, a reminder that my stubbornness had a price. For now, that price came in ointment and the gentle reprimands of the infirmary medic and the soft, worrying hums from Hana.

Whispers found me regardless.

I walked into combat studies under a thin rain of gossip. Heads turned in the way the wards turned toward moonlight—automatic, approving, a little hungry. Students who had never looked twice now glided three degrees closer to give me more cinematic angles. I heard snatches: “Nullborn,” “did you see that shot?” “He burned his hand.” One group laughed and then tried to look casual about it and failed.

It should have been embarrassing. Instead it felt like a pressure I could use. I breathed in the noise and let my shoulders take the shape of it. This is what I had wanted in a way I didn’t know I could want: not the spotlight itself, but the possibility that the world would notice my work.

I took my seat, the desk’s rune staying politely dim under my elbow—my rune, like most other runes around Seiryoku, did not answer me. It never had. It’s a small, default kind of cruelty in a place built to praise magic: the desks glowed, the runes sang, and my chalk symbol stayed black. So I did what I always did. I opened my notebook and drew.

Lines come easier than sparks. The barrel shape appeared, patient and inevitable, the geometry of a chamber sliding toward a circle. Hands that had learned soldering in secret and filing in stolen hours felt for the way metal wanted to be where a human hand could find it. The thought of machines that would speak without bloodlines warmed my chest.

“Wow,” a voice near the aisle breathed. “That’s him.”

“Yep.” Someone else, awed or amused—it’s hard to tell sometimes at Seiryoku—added, “He fights fire with a gun. That is so on-brand for a protagonist.”

I almost smiled. The joke stung with truth, but it was my truth now. I reached into my pocket and felt the dull weight of the single charged crystal we had left from the midterm. It still held the memory of flame like a keepsake: not bright, not ready, but remembering the heat.

Class passed in a blur of lecture and demonstration. The instructor moved through the room like a tide regulator, correcting stances, reminding students where to place their weight, and sending polite barbs down rows designed to snap egos back to useful sizes. “Kuroganezu,” he said once—my name tasted new in the air—“you can put the notebook away and watch the demonstrations. Observing is a skill.”

I did. I watched the arcs and moves and the way the students who were born in favor of mana made everything look almost lazy. It was a skill, and I had to learn it not from light but from counter-light: from the mechanics of pull and counter-pull, from the way a blade asked your body to breathe differently, from how the tiniest angle changes the whole story.

After class, the courtyard turned into a swarm. Students clustered in groups and compared notes, reenacted the midterm in exaggerated pantomimes, and exchanged the kind of bets that mostly existed to sharpen tongues. I moved through that swarm with Renji like I’d learned how to wear weather. He embedded himself on my arm like a bright curse—impossible to ignore, impossible to dislike.

“First period was drama,” he said, raking his fingers through his hair. “Second period was glory. Third period—practical improvements. Do you know what that means?”

“Lunch?” I offered.

“Scientific field test,” he said, grinning. “But lunch is more honest. Workshop afterwards. We finish the revolver cradle.”

“Work not finished,” I corrected.

“Semantics,” he said. “Also, listen. People are saying things.”

“They always are,” I said.

“No, it’s better now.” He jabbed a finger at a passing poster where a tiny animation of a girl’s rune spark cycled. “Two weeks ago, people would’ve shoved you out of the lobby. Today they shove you because they want your autograph. That’s growth.”

I would not have called it growth exactly. I’d call it noticing. Saying that out loud would make it sound like an achievement. Renji wouldn’t let it go. He kept talking until the bells moved our feet into other places and I had to split away for appointments with the classroom and with my own breath.

The med bay smelled like antiseptic and rain when I slipped in. Hana was there first, cheeks a little pink from the climb and from the fact that she’d been trying to be brave all morning. She’d claimed the corner chair as if it belonged to the kind of person who stitched up other people’s broken edges. She always tucked a thermos into her bag like a promise.

“You look like you fight with your eyebrows,” she said, which was one of the cutest ways to be worried that she’d ever said.

“Which eyebrow?” I asked. “Is it the left one that barks or the right one that plans?”

“You’re insufferable,” she murmured, but the way she said it slid into a smile. Then she looked at my hand.

The medic fussed with gauze and a tin of something that steamed cold when it met skin. The cut where the crystal cradle had kissed my palm had healed in a funny way—scar tissue like a rug that didn’t want to lie flat. The medic droned instructions for care and then left us alone, trusting Han’s hands more than an overworked nurse trusted words.

Hana hummed while she worked. It was a tiny sound at first—something she used when she concentrated hard enough to make the world think she knew how to sit still. I’d heard it before in the workshop when she was handing solder like prayer. Now the hum wrapped around my fingers like a band and eased the sting. It wasn’t a spell the way Ayaka’s fire was a spell, not loud and loud enough to warm the courtyard. It was more like an answer: a small permission for flesh to behave.

“Better?” she asked.

“Better,” I said. “Thanks.”

She brushed away a fine dust of bandage lint and then, like she always did when embarrassment came close, looked anywhere but at me. “You should rest, Temo. You did a lot yesterday.”

“We won,” I said before I could stop myself. The word tasted strange in my mouth. “We won,” I repeated.

She looked at me then, and whatever sentence she’d been going to speak rearranged itself. “You did very well,” she said, quietly staunch. It isn’t the same as being praised by a teacher or by the crowd. It’s steadier than applause. It’s a little like being anchored.

The day moved along with a thousand tiny obligations. The city outside Seiryoku’s gates smelled of rain and hot metal that day—somewhere, mana-smiths were tempering a batch of new rune cores, and the smell came across the campus like a rumor.

By midafternoon the Outcasts convened in the workshop by habit and conspiracy. The Applied Thaumaturgy room belonged to people who liked their chaos stored in labeled jars. Benches sagged under projects, whiteboards carried half the city’s math, and an old barrier projector sat in the corner like a retired beast. Renji had set up a station that looked like a shrine to improvisation: tools in neat disorder, a spool of wire humming like it had opinions, and a box of relic rune fittings stacked like trophy parts.

“Okay,” Renji said, snapping his fingers. “We’re not cry about yesterday. We are do invention. Big step: revolve-cradle. It rotates. It will be glorious.”

Kenji, who smelled faintly of math and certainty, didn’t even look up from a stack of papers when he said, “In conversation with the laws of physics, we will be the provocative friend who attempts to make them reconsider.”

“I like his optimism,” Renji said, delivering the compliment like a precision strike. He turned to me, eyes bright as a soldering iron. “What do you want it to do?”

“Hold crystals,” I said—said simple and honest because it was what we needed. “Index them. Let me rotate without glancing. Reduce the finger work.”

Renji clapped like we’d announced a festival. “Booyah. Indexing detent. Ball bearing (but smaller). Quick-release. And—the best part—detachable bayonet.”

“Bayonet?” Kenji’s voice was the exact blend of suspicion and documentation. “You are literally inventing an implement that could be used as both a blade and a projectile instrument. History will have feelings.”

“We’ll start with a proof of concept,” I said. “Not a blade-sword hybrid fantasy. A working attachment that locks under the barrel so I can handle close without the gun.”

Renji made a sound like an engine revving and then deflated into a grin. He pointed at a wrapped package on the bench with religious fervor. “Prototype mount,” he said. “Slide-in dovetail, lock with a quarter-turn, safety notch. If it cuts a bit of wire, that’s a bonus.”

Kenji pushed up his glasses and unrolled a schematic with the solemnity of a man presenting a theorem. The detent geometry looked like a city map only he could read; the indexing grooves were marked with tiny annotations. “If you build the detent correctly and trade off some mass in the barrel shroud, you can keep the balance near the grip. But you will have to file precisely .3 mm, or it will jiggle. Seconds of jiggle are something of a mortality risk in close quarters.”

“Great,” said Renji. “We do the thing that is not-jiggle.”

Hana brought out two cups of tea, the ritual of her hands competent and small. She set one in front of me, one in front of Renji, and then sat where she always sat—beside me but not touching unless touching was needed. Her humming slid quietly under the discussion, not to change the physics but to keep us from dissolving into panic about the complexity of our own optimism.

We started. Files sang, embossing a plan into the metal. I sanded a dovetail while Renji fiddled with an indexing ring that he insisted must have “just the right amount of personality.” Kenji measured with micrometer concentration. Hana fetched spare rivets and kept the morale present in the room by offering cookies when Renji’s fingers began to shake.

“No tests today,” I said—a rule I thought reasonable and then muttered to myself like a parent. “We’ll do the mechanism today. Dry-cycle. Check tolerances. Don’t point it.”

“Poetry,” Renji said. “Also hygiene.”

The cylinder went into place for the first time like a heartbeat clicking into its chest. I fitted it and the grooves matched with a satisfying kiss. The indexing detent fit neatly with its notch. The mechanical music of the machine was small and good. No rune glowed, no crystal sang. Empty chambers spun clockwise under my thumb like planets waiting for a sun.

“We’ve only got one charged crystal,” I reminded them. “The others are empty. They’re useless until we can feed them—or find a way to shape charge into them.”

Renji’s grin didn’t dim. “We’ll feed them. We’re not out of wild ideas yet.”

Kenji sighed and then took a breath that was equal parts annoyance and delight. “We will make sure the mechanical system is not going to amplify failure. If the worst-case scenario is a few blown fuses and a singed eyebrow, we be angry but alive.”

“Good standard,” Renji said.

Hana bound a small piece of cloth into the bayonet prototype handle to make it less slippery. She didn’t ask why we were doing this. She asked how she could help. That meant more than she realized. Sometimes help is not the answer; sometimes help is the ground that prevents you from sliding off the cliff while you learn to fly.

I worked the mock-up into my hand. Balance shifted. The mount added weight, but the placement under the barrel kept the pivot close enough to the wrist that the gun felt like a tool again—not a club. The bayonet’s teeth were crude but decisive. The idea of it lodged under the barrel felt honest: close tool for close problems, distance tool for distance problems.

We set the prototype down like a sleeping thing. No live firing. No points to prove. The workshop smelled like metal and tea and a small, concentrated hope.

Renji stepped back and, with the theatrics of a man who had been given permission to be dramatic, pulled a cloth away from the newest piece. The revolver chamber was not finished. It was not beautiful; it was honest. The metal had filing marks that caught the light in unkind ways. The indexing ring still had burrs younger than we’d like. The dovetail for the bayonet had a hairline we would file next week.

But the cylinder clicked. It turned with a firm, deliberate motion. The mount slid under the barrel and locked with a quarter-turn. The detent popped into notch like a promise.

“Mark One,” Renji declared in a triumphant whisper that sounded like the birth of a plan. “Or…Mark Zero point nine-nine, if we’re being honest.”

Kenji took a photo with his datapad and then immediately tutted at his own lack of restraint. “Photographic log complete. Don’t test it live.”

Hana smiled, small and real. She leaned forward and touched the metal where my hand would rest. “It looks like it will fit your palm.”

“It does,” I said, as if trying it on were not a metaphor.

We wrapped the thing in soft cloth and slid it back into its case like a creature you intended to raise. The workshop exhaled and we went outside into the fading day.

The board in the West Gallery had not changed its mind about the world. Names were names. People were people. But when I looked at the case with Mark One inside, I felt like something in the world had been moved a fraction, and not by the wards or the runes, but by us.

We went to the rooftop. We sat where the city looked like a memory turned into a skyline. Renji insisted on bylaws. Kenji proposed a probability matrix. Hana offered cookies. I wrote in the notebook in small hurried letters: MAKE HER FIGHT MY STORY.

It was not a vow. It was an outline.

The day closed with the city’s lamps like a field of tiny testaments. I wrapped my bandage tighter, not because it hurt more but because it felt like armor. My hand would heal. The last duel had not solved the world’s problems. It had made a space for us to keep trying.

When I went to sleep, the sketch of the revolver cylinder lay under my pillow like a schematic for a second chance. Outside the dorm, Seiryoku’s wards hummed the night into a watchful lullaby. The next semester would be loud. The next fights would be sharper.

But for tonight, we had metal that turned, a blade that clicked in, and a promise that we wouldn’t let other people write the timing of our story.

Tomorrow, we would begin the next step.

Please sign in to leave a comment.