Chapter 9:

Revolver Dreams, Empty Chambers

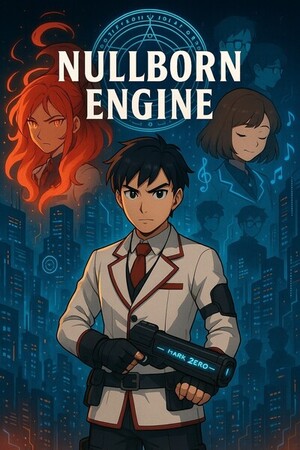

Nullborn Engine

The training yard smelled like a mistake you could still fix: dust, old sweat, and the faint metallic tang left where a rune had spat and been put back into line. The smell stuck to the soles of my shoes and the back of my throat, like the world reminding me of lessons in a language that favored repetition.

Kaien’s drills had gotten meaner since the boardings went up. Not mean like cruelty—mean like a teacher who tightened the metronome until rhythm stopped being optional. He set the tempo and expected the feet that followed to know how to keep the beat without tripping on pride.

“Again,” he said. The word was the school’s metronome.

Step, slide, pivot. The same geometry I’d practiced until my calves grew patient. The practice blade tasted like old wood and required no apology. I moved in the pattern until choices folded into instinct.

When he finally let us rest, the sun had the worn look of a lamp that had been turned on for a long rehearsal. My shirt clung to me with honest sweat. Renji found me first, like a comet that had arranged its own orbit around caffeine.

“You look like an art exhibit for bruises,” he said. “We have time to tune.”

“I’m not the exhibit,” I panted. “The gun is.”

“We’re not—” He stopped. He looked at my bandage and then at the way my hand flexed and decided, like a reliable ally, that small victories deserved snacks. “Workshop. Now.”

The Applied Thaumaturgy room was already warm with small industry. The benches were a terrain of tools and tins. A coil of wire slept under a crate. Someone had duct-taped a schematic to the wall and called it inspiration. Renji slammed his bag down and began unpacking components like a man reassembling a personal mythology.

Kenji found a place to write everything down. He did it with the kind of precision that made you feel safer and more exposed at once—safe because logic at least existed, exposed because logic does not always have a heart.

“I measured your indexing detent last night while you were asleep,” he said without irony. “It was a restful act of cruelty and I apologize to your dreams.”

“Thanks,” I said, and tried not to count the ways Kenji’s concern came coded as math.

We set Mark One on the bench like a sleeping animal that might purr if you scratched it correctly. The cylinder gleamed with raw edges that Renji had not yet sanded into charm. The dovetail for the bayonet sat patient and open beneath the barrel.

“We have one charged crystal,” Renji said. “Limitations: charge retention is unpredictable after a forced discharge—like yesterday’s episode. Recharge time depends on ambient mana density and the crystal’s spectral affinity.”

Kenji’s pen stabbed a graph. “Observable recharge window: six to thirty-two hours, with a heavy bias to the upper bound in our tests. In layman’s terms: it’s grumpy.”

I turned that poor thing in my palm. The crystal still had that memory of fire inside; the edge of its facets hummed like a scab that remembered flame. We were lucky to have even one charging. The rest of the crystals in our kit were hollow glass now—empty, clear, useless as any object that spent its life waiting.

“First goal,” Renji said. “Make sure the cylinder indexes clean. Second goal: dry-cycle and positive stop. Third goal: balance with the bayonet attached. Fourth goal: don’t light anything on fire unless you are emotionally prepared.”

“Fifth goal,” Kenji supplied, without looking up, “don’t be the piece of evidence.”

“Poetry,” Renji said. He handed me the frame like a liturgical object: careful, proud, absurd.

We ran dry cycles. Click, rotate, detent, reset. The mechanical rhythm was good in my palm. The sight rune—crooked as ever, because Renji insisted crooked meant personality—lined up with the cylinder window like a scowl. No runes glowed bright; the room was patient and polite.

Then we moved to balance.

The bayonet clipped into the dovetail with a little complaint of metal; it slid home and locked with a satisfying quarter turn. Attaching it shifted the center of gravity forward the way adding a new idea can shift how you stand. For a second the gun in my hands felt proud and ridiculous simultaneously.

“You feel that?” Renji said. He was always watching the micro-expression that told him whether his inventions would be beloved or merely tolerated.

“Like a tool that wants to be two things,” I said. “Close and far.”

“It’s an identity crisis,” he said. “We’ll fix it with geometry.”

Kenji took out calipers and whispered numbers into a recorder like they might be spells. “Move the balance point back fifteen millimeters and reduce nose mass by swapping to honeycomb baffle. That will decrease polar inertia by—”

“I’ve never been so excited to be told to shave my gun,” I said.

We filed and ground and coaxed the prototype. Bells in the hall chimed and blocked us from mercy. Renji brought tea in a thermos like it was an offering to invention gods; Hana handed out the last of her homemade onigiri like she was saying the words care and nourishment in rice.

“You should test it,” Renji said finally, eyes bright with the possibility of results.

Kenji didn’t look convinced. “We can perform a dry index test. Live discharge is unwise until we have spare containment and an engineer who is willing to be the sacrificial lamb in the event of unpredictable detonation.”

Renji scoffed. “Kenji is a man who would sacrifice a spreadsheet before a person.”

“He would sacrifice both if it increased predictive accuracy,” Kenji said.

The plan ended with a compromise: dry cycles and a careful, limited test of the fire crystal’s charge behavior on a containment dummy—a rune-glass target designed to absorb a puff and nothing more. No live projectile. Just a cough. If the crystal could cough through the Mark One frame, we would consider progress.

We prepared the chamber. The single fire crystal—our trophy—slotted into the cradle with a deliberate, almost prayerful motion. The rune lattice around the cylinder warmed faintly, like a cat that wants to be petted. We tightened shields, placed the empty target, and rigged the bench with grounding lines Renji had insisted on.

“On my mark,” he said. “One—two—”

The crystal glowed a lazy ember, then a tiny sound came from the frame, the mechanism breathing in a way we hadn’t made it do before. A faint puff of light rose from the barrel—like a candle snuffle, not a torch. The target bloomed with a quiet glow and then sighed back to sleep.

We exhaled as one organism. The room let out the kind of laugh you have when something terrifying stays polite.

“It coughed,” Renji said, triumphant. “It coughed on cue.”

Kenji’s satisfaction was an unembarrassed spreadsheet. “Discharge negligible. Containment integrity within expected margins. Recharge projection: data insufficient to model short-term behavior with fidelity.”

“Translation,” I asked.

“It works,” Renji said. “But it takes a nap afterward.”

“Good nap,” Kenji clarified. “Expensive nap.”

We celebrated minimally with more tea and a plate of Renji’s celebratory crackers that were likely to cause regret but felt necessary. Hana’s humming threaded through the room, not large enough to be noticed if you didn’t know to listen, but it wrapped the frayed edges of my hand like a tiny bandage that actually did something. My skin cooled faster than it should have. The scab twitched and arranged itself back into something less raw. I let myself be comforted and called it field maintenance.

“Do you ever tell them?” Kenji asked suddenly, almost guilty. “About the humming.”

“Tell who?” Renji asked, because Renji’s taxonomy of people who needed telling was both specific and broad.

“Anyone,” Kenji said. “The warden. Kaien. Society.”

Hana’s hand paused over a cookie. She looked at her palm, at the small constellation of repair she’d made with thread and song and not-fully-named things, and blinked.

“It’s…my thing,” she said, voice small. “It’s not big. It’s more like—” She swallowed. “It helps.”

Renji looked relieved in the way men are relieved when someone admits to being cute but competent. “It’s adorable,” he said, with affection and immediate pride.

Kenji made a note, then smoothed his expression into something that read: this may be an advantage.

We pushed the testing into small experiments for the rest of the day. Dry cycles, fit checks, the cylinder indexing cleanly or near enough. Each test taught the prototype a little more about the world and made the world reciprocate with information. No firing, except the cough. No fireworks. No fame.

Which left us with enough time for the dorm parody that we didn’t know we needed.

Renji’s idea for team cohesion was a sleepover. Not the romantic fluff you imagine—more a tactical seeding of morale with snacks, diagrams, and late-night debate. We planned to meet in his room because he claimed his family’s antique futon had character. Kenji said the odds favored the futon collapsing on the hypothesis of snack-related gravity but agreed to attend for data collection.

“Rules,” Renji said when we arrived: “One: no heavy weaponry into bed. Two: no live crystals under covers. Three: sleepwear is optional but strongly encouraged.”

Hana had a modest pair of pajamas—soft, practical, and comfort-engineered. Kenji arrived in what could only be described as “study chic” (glasses, cardigan, an air that smelled faintly of marginalia). Renji wore a robe that may in fact have been an homage to all the best embroidered things in the city. I brought my notebook and a reluctant sense of camaraderie.

We were three minutes into assembling a cautious calm when the door to the communal lounge swung open and an alarming number of second-years flooded the room in themed sleepwear. Someone had organized a “nostalgia pajama party” and the timing was tragically perfect.

It was the kind of scene the Academy specialized in: a group of earnest students convinced they were having a private festival in public.

Renji’s robe felt suddenly very on-brand. Kenji pretended to read and failed. Hana hid behind her scarf and pretended not to be flattered when two girls asked her about making the tea.

Then the PA system crackled to life with a bored prefect declaring a dorm inspection. Panic is contagious; it spread faster than gossip. People grabbed blankets, pretended to be asleep, straightened pillows with terrible precision.

In the chaos a resident prefect—a girl with a clipboard and determination—materialized and pointed at our cluster like a general calling attention to the one unit that had decided to be an island. “First-years,” she said, and for the record it came out as a command and a compliment.

We, being first-years, did what first-years do: we tried to look like we’d been holding a formal salon for the express purpose of educational conversation.

At just the wrong moment, someone shoved a tray of noodles between tables, which triggered the “someone will spill something” reflex and twenty dumplings performed an arc I’d memorized in a physics class. A particularly daring silicone charm fell out of Renji’s robe and clinked against the table with an ungainly sound.

Hana clapped a hand over her mouth, and in that second of vulnerability she blushed so fiercely that the cafeteria’s lanterns might have dimmed to honor the display. The room, sensing drama, split into a dozen small conspiracies.

The prefect stared at us, then at Renji’s robe, then at the dumpling arc. “Is this a gathering organized by the Outcasts Club?” she demanded.

“We—” Renji began, and then did the only sane thing a bombastic operative can: he invented bylaws. “Article One: We do not die. Article Two: We bring snacks. Article Three: We are wholly and entirely registered under no formal charter.”

The prefect considered arresting us for unlicensed charm and then, mercifully, decided this was juvenile and beneath her—unless someone actually spilled soup on the dorm rug, which would be a crime against the campus aesthetic. She moved on.

We let out a collective breath long enough to make the lamps sigh. Renji collected the noodles that hadn’t escaped the table like trophies. Kenji adjusted his cardigan like everything was fine. Hana offered the prefect a cup of tea as if she were sealing a treaty. The prefect accepted and hummed a little in something I could not name but respected.

When the room finally settled, both Hana and Ayaka—who’d appeared mysteriously just to ensure discipline, as one does—ended up on opposite sides of me, both offering advice in their own currency. Ayaka suggested targeted sparring to tighten my arcs; Hana suggested a sequence of restorative stretches and the idea of a bandage pattern to reduce blistering.

Both of them sat close enough that my torso registered it as noteworthy. There is an arithmetic of proximity, and that night the sum of it made my chest weigh pleasantly and alarmingly heavy.

“Don’t let them turn you into a spectacle,” Ayaka said, flat and precise. “Use the attention.”

Hana looked at me with the gravity of someone who tended to both physical wounds and the small fragile things that fold under them. “We’ll help,” she said.

Renji, in his infinite capacity for dramatic timing, misread the quiet as permission to loudly propose a ridiculous badge for our club. “Outcasts Club pin? Totally will be sewn with love and regret.”

Kenji, who’d been quietly compiling probabilities for social fallout, merely drew a small Venn diagram that involved snacks and survival.

We laughed like people who had nearly been congratulated for not burning a building down. The joke held us together.

Later, walking back through the campus, I felt the weight of eyes again—less a gaze and more a pressure that felt like being named in a sentence. People had opinions now. People had stakes in my failures. I had to carry that without letting it crush the part of me that wanted to build.

We slept like people who had deadlines and ecosystems of hope. The sky watched, polite and indifferent.

The next morning, the workshop called us back. The cylinder still sat in its case, but we’d learned things overnight: the detent needed refining, the bayonet needed a spine, and the single charged crystal needed a nap when it had been asked to cough.

That afternoon the rumor mill picked up and spun a little faster. Attendance at our bench in the workshop increased not out of curiosity but for reasons that were complicated and not entirely flattering. New faces paused at the door, watched us with the kind of attention that felt like reconnaissance.

I noticed it and then pretended not to. That’s a skill I was learning at Seiryoku: how to hear the crowd without letting it pull the strings on your chest.

The Mark One’s cylinder turned in my hand, indifferent and promising. It would not do magic by itself. It required us—hands, decisions, repetition. The empty chambers were not failure; they were possibility. The charged crystal’s ember was not power but potential.

We had work to do. We had to learn to ask the world for permission without begging.

That night, when I set the prototype on my bedside table, the weight of it was not a threat. It was a tool that awaited practice. The city hummed beyond my window, an orchestra that had not yet learned the piece we would one day play.

And in the quiet before sleep, I heard Hana’s hum in my memory like a promise. For the first time in a long time, I felt less like someone the world had already decided for and more like someone who could decide back.

Tomorrow, we would test again. Tomorrow, we would file metal and honor mistakes. Tomorrow, the empty chambers would mean less.

For now, the proof of concept lived in the case, in our hands, and in the slow, steady work we were willing to put into making machines that spoke the language we did not inherit. The revolution would be small and stubborn at first; it would begin with dry cycles and patient filing and a hum that was quiet enough to be a secret and strong enough to be medicine.

That was enough to sleep on.

Please sign in to leave a comment.