Chapter 10:

Chapter 10: A Mother’s Madness

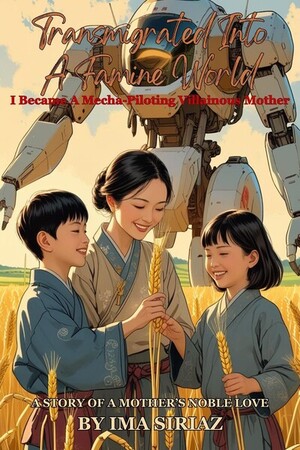

Transmigrated Into A Famine World, I Became A Mecha-piloting Villainous Mother

The sun made its slow pilgrimage from the eastern rim of the sky to the west, dragging the day with it. Shadows stretched long and thin across the yard, creeping from one end to the other like the hands of an unseen clock marking the hours. Aina stood at the front gate, her gaze fixed on the empty road. With every lengthening shadow her unease grew heavier, and her mind betrayed her with cruel whispers. Whispers that drew visions of her sons lost, hurt, or worse.

Her sons. Hers. The words echoed quietly in her heart like a secret she dared not speak aloud. She hadn’t birthed them herself, true. She didn’t suffer the pains of childbirth, also true. But in every way that mattered, she was their mother. At least, that was how she chose to see it, even if their wary eyes and guarded silence reminded her that the sentiment was one-sided.

Only when the sun dipped low in the western sky, bleeding gold across the horizon, did Irek and Varn finally appear at the gate.

“Mother, we just got back from the city… We managed to sell all the lacquerware for three hundred coins, but this was all we could get.” Irek lifted a sack of grain, no heavier than ten kilograms.

He handed her the coin pouch, and Aina poured the contents into her palm, twenty coins glinting weakly in the fading light. It didn't look like much at all.

Her mind did the calculation instantly. Two-hundred eighty coins for ten kilograms of rye. That meant twenty-eight coins per kilo. Twenty-eight coins per kilo, for rye.

Her lips pressed into a thin line, a sign of displeasure. Three years ago, a kilo of rye flour cost five coins. Now even rough grain was worth nearly six times as much.

She wasn’t shocked, to be honest. The entire region had suffered through two years of drought. Only a fool would believe merchants wouldn’t seize the chance to squeeze desperate villagers. She couldn’t even resent them. She would be more surprised if there were honest merchants willing to maintain pre-drought prices and probably take a loss.

She herself might have done the same if it was her in their shoes. The only thing she would have done differently was hoard much earlier and then resell at profit. She sighed, quietly cursing the former Rinia’s lack of foresight. But then, what foresight could be expected of an uneducated peasant woman?

Tomorrow, she decided, she and the girls would have to climb farther than before. Maybe even to a mountain no villager dared to tread. Dangerous, yes, but the old paths were already barren. There was a reason people avoided the unexplored peaks. That reason was the giant mountain beasts.

Regarding that, only yesterday did she learn the name of the village she now called home.

Wyrmrest Hollow.

And the name of the village was directly related to the mountain beasts.

According to folklore, the valley had once been the resting place of a colossal serpent, larger in size than any other mountain beast. It had curled up to sleep and never awoken, its body eventually buried beneath centuries of drifting soil until it was completely covered up in soil and rocks. Then an entire village grew above its corpse. The tale went that lesser mountain beasts kept their distance out of fear of the wyrm’s lingering presence.

Aina wasn’t convinced. Not because she dismissed superstition as a modern woman, but because she had seen the scars of past attacks with her own eyes. The beasts had come before, laying waste to the village in their fury, and they would surely come again. Folklore was no shield. Old Man Jine said as much himself, waving the story away as nothing more than wishful thinking. He called it a rubbish bedtime story better forgotten before it gave children false hope

The village was so isolated that reaching the county town on foot took half a day at best. Or longer if one had children or carts to drag along. By comparison, even Richfield, the backwater hamlet where Rhielle hailed from, was practically next door to civilization, a mere hour’s walk from the county town. Aina often wondered why the founding fathers had chosen such a god-forsaken, out-of-the-way place to sink their roots.

Not even Old Man Jine, whose family name traced back to the very first settlers, could give an answer. Whenever pressed, he would only shrug and mutter, “They must have seen something worth staying for.” If such a reason had ever existed, it had long since withered and forgotten.

And now, with no chief left to guide them, the remaining villagers, those too poor, too stubborn, or too broken to join the exodus, turned to Old Man Jine for leadership, as though age alone granted wisdom. His words carried weight. It wasn’t because he was the most wise or the strongest, but because there was no one else older than him who was of sound mind and body.

“Tell me,” he said that evening. Seated on a rough stool outside his home, the others gathered in a half-circle around him, “how much food do you have left?”

That question silenced the group. Faces turned downward, eyes fixed on the dirt. Everyone knew that to speak aloud how much food they had stored was to make themselves a target. Hunger sharpened envy into knives. In these difficult times, knives could easily be turned on neighbours. And with how few villagers are left, those who fell to treachery probably would never be discovered.

The silence stretched, taut and uneasy. Finally, Old Man Jine sighed and spoke again. “I’ll start.” He called for his wife to bring out a small fired clay pot of rye, barely the size of a person’s head. “This much, and six more of the same.”

Murmurs rippled through the group. Some stared at the small pot, others at Jine’s weathered face. They couldn’t believe he would outright tell everyone how much food he had, yet by laying his own cards on the table, he left the others no excuse to stay silent

Aina swallowed hard. Her instincts told her to remain quiet, to hoard what little her children had scraped together. But another part of her, the part that had seen corporate meetings, ledger books, and the brutal logic of shared risk, forced her to speak. To take a chance.

She detailed what remained at home. Specifying a sack of grain carefully rationed, a few bundles of wild greens her daughters had gathered, and a few handfuls of chestnuts hidden in a jar. Not much. Not nearly enough. Still, she omitted the smallest stash she had tucked away, just in case. A single mother’s insurance against tomorrow.

Her honesty startled the others. After a long, awkward pause, one family admitted they had only a small pot of peas. Another revealed their jar of pickled roots had spoiled and only jerkies were left. One by one, the grim tally was laid bare, and it became clear that among them, only Old Man Jine’s household had anything resembling a real store.

The worst off was the Kurns, a farming family from the far edge of the village. Their gaunt faces spoke before their words did. They confessed to having nothing left. No grain, no beans, not even a scrap of dried meat.

Aina had never spoken with them before, and their seeming friendliness to her felt awkward. But her sons whispered to her that the patriarch of the Kurns had once marched alongside their father, conscripted into the same company during the war eight years ago. He was the man who had returned with news of their father’s death

Old Man Jine listened, then pushed himself to his feet with a groan. He disappeared into his house and spoke to his wife in hushed whispers. The villagers shifted uneasily, some expecting anger, others fearing a lecture. Instead, the old man emerged with difficulty, a heavy sack slung over his shoulder. Grain.

Without a word, he began measuring by bowls, distributing according to each household’s size. Aina’s family received their portion as well, the sight of clean kernels enough to make their throats tighten with gratitude. And to the worst off families, Old Man Jine gave a few more bowl’s worth of grain.

For a moment, no one moved. The gift was too strange, too generous. Suspicion hung thick in the air. Who would part with their own food in times of famine? Could there be poison in the grain?

“It’s old stock,” Jine said without a change in tone, as though reading their thoughts. “Grain I hoarded years back. It may not keep for much longer. Better you eat it than let it rot.”

Some nodded, thinking that it made sense. Aina, however, lifted a handful to her nose. It smelled fine. No mold, no strange smell. It smelled fresh enough. She didn’t believe him, not entirely. But she didn’t question it either. She wasn’t a farmer; she couldn’t tell good from bad by smell alone. And more importantly, food was food

She wasn’t going to question where food was coming from. What mattered wasn’t whether Old Man Jine had lied. What mattered was that, for tonight at least, her children would eat.

She remembered the hunger when her family had run out of food earlier that year. The gnawing emptiness that water could not fill, no matter how much they drank soups so thin it was practically plain water. Soup boiled from weeds no longer fooled the body. To stave off hunger, they drank water, but water was just water. Water wasn’t food. Irek’s efforts of carrying water several times a day, noble as it was, amounted to nothing more than prolonging the suffering

There was no food. No strength left to walk to the city, no parents she could turn to for help. She was without hope. Her husband had died seven years before, leaving only five thousand coins in compensation. That money was long since spent on survival, and on finding a bride for Irek.

Thinking back, maybe she was short-sighted when she found Irek a bride. She thought if at least Irek and his wife could survive, at least her husband’s bloodline and hers wouldn’t end there. She thought leaving behind descendants was all that mattered. Blame it on her being stupid or starving to the point of being narrow-minded, but she failed to think about what would happen to the rest of her children.

Or to her daughter-in-law.

She failed to understand that bringing home a daughter-in-law simply meant that one more person would starve to death. Instead of five mouths eating a kilogram of grain, now six mouths would eat a kilogram of grain. And so they only ended up dying together faster.

When she realized her mistake, it was too late. The grain pot was more bottom than grain. The dried vegetables and fish were all long-gone.

In despair, she had taken a knife and carved a piece of flesh from her own thigh. She left it on the table, a grotesque offering for her children, then dragged herself away on trembling arms, her leg bound in bloody rags. Blind with pain, she stumbled into the forest until she reached a quiet pond. There she collapsed by the serene pond, ready to close her eyes forever.

But fate mocked her. When she woke, the wound had scabbed over. Somehow, she still lived. Somehow, she had failed even at dying.

She had dragged herself home beneath the moonlight, each step an indescribable agony despite the hunger dulling the pain. When at last she arrived, she found a single bowl waiting on the table. A thin broth, one ragged strip of meat floating inside. Her own flesh.

She had choked on her own sobs then. Not from horror, but from joy. Her children, though she had tried to make them despise her, had still thought of her. They still saved something for her, their hated, cruel and abusive mother.

They were such good children. Good children indeed. Too good for her. She did not deserve them. She prayed they would learn to hate her, for it would be easier that way. No need to grieve, and easier for them to move on without memories of her.

And now, as Rinia’s vision blurred, the present tangled with the past. The situation was almost the same as then. But they were better off now than then. A few grains left, a handful of wild greens, maybe a week of survival. Or two weeks of survival at most if they ration their food well.

But this time, Rinia swore she would not make the same mistake. Not six mouths. Five. Only five mouths should be eating. Five could last longer, if the food was rationed carefully. Rinia believed they could. Rinia believed that her children would live well, even without her.

Rinia had lingered around for too long already. She had lived for far too long since her husband’s passing. She should have followed him back then. Perhaps this time, her flesh would feed them better.

She was not necessary. She never had been. Only her children mattered. A bad mother should vanish, so that her children might live. It was only right.

“Mother, stop!”

“Husband, take the knife!”

“What are you doing, mother?!”

Voices echoed in her ears, faint and far away. Rinia thought it was kind of her children to come see her one last time. But such sentiment wasn’t necessary. She was a bad mother, wasn’t she? She had beaten them too often, hurt them too much. Surely they hated her by now. Better they let her die quietly by the roadside, unloved and unmourned. There was no need for such a big fuss.

"Mother!"

Please... be quiet. Let mother die in peace.

“MOTHER!”

The roar jolted her like a slap. In fact, her face did burn, her cheeks stinging sharply. Blinking, she found herself surrounded. On her right, Varn clung desperately to her arm. On her left, Rhielle held the other, refusing to let go. Her legs were pinned by her youngest son and by Hunter Gen’s strong grip.

And before her eyes, her eldest son.

Irek’s hands pressed against her face, holding her still, his eyes brimming. His tears fell onto her cheeks like long-awaited rain.

“Please stop, Mother,” he sobbed. “Don’t leave us again.”

“Please, Mother,” Rhielle pleaded.

“Fight it, Mother! You’ve just got better!” Varn cried.

“Mother, we need you. Please come back,” Tallo begged.

“Mother, don’t leave Vila,” came the youngest daughter’s sobbing voice as she laid down on Rinia’s belly, as if trying to use her body to stop Rinia from getting up.

Their words battered her heart. For a moment there, she sank under the weight of her despair, convinced that her death would save them. That by dying she would give her children a better life. But then, the voice of her children begging her to live smashed open a wall in her mind, and from the cracks, hope and light came to the surface again.

Her heart thundered as sanity crawled its way back. Something wasn’t right. She realized, with dawning horror, that those weren’t her thoughts. Those weren’t her own despairing wishes. She had been swallowed whole by someone else’s pain.

With a chill that sank deep into her bones, Rinia - no, Aina finally understood. Something was terribly wrong. This wasn’t her memories, nor her feelings. This was Rinia’s.

Rinia’s overpowering madness had risen from the grave and wrapped itself around Aina’s soul!

Please sign in to leave a comment.