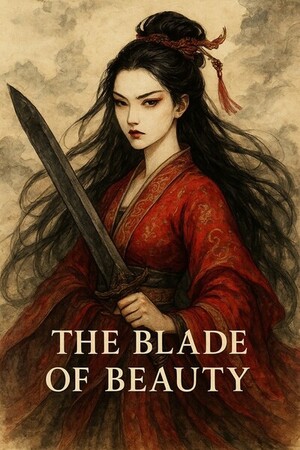

Chapter 34:

The Transformation

I, a Hermaphrodite, Live by Taking Lives

According to the letter, I had three days left before the “change.” During those three days my strength would plummet; I would feel like clay in someone’s hands, heavy and limp, and unbearably drowsy — apt to fall asleep standing up. Fortunately the whole episode lasted only seven days.

I had planned to hole up in an inn and sleep the seven days through. But after asking around I learned that Shaodu had been restless lately. I tried over ten inns; none would take me in. Even at twenty gold coins a night the innkeepers shut their doors in my face. Did I look like trouble? I almost returned to the West Jin manor — but then I thought about how unpredictable the change could be. What if I shifted into a woman? Given Gongsun Yanshu’s tastes and disregard for life and death, I felt I might be in real danger…

After wandering for half a day, convinced I would have to sleep in the street if I didn’t find shelter, I gave up and decided to seek out an old friend on Sishui Street.

Sishui Street was the most prosperous road in Shaodu, where nobles lived. Because it lay closest to the palace, officials who needed to get to court in a hurry bought houses there. Over time it had earned the nickname “Nobles’ Row.” Every few paces you’d meet scribes and ministers; walk further inward and you’d reach the famous General’s Residence.

That residence had once been my home.

I had been the general’s only son, but because I was born hermaphroditic my father never accepted me. He’d nearly killed me once; but my master rescued me and set me on the path of cultivation. I swore then — even if I starved, were tortured, or torn limb from limb — I would never go back to that household.

The person I sought was the only light in my dark childhood, the one who raised me.

Old Nanny Zhang — my wet nurse.

She had served in the General’s household for fifty years. I couldn’t tell you her exact age, only that it was enormous, too large for me to truly imagine. She had already been elderly when I still lived there; wrinkles marched from the corners of her eyes down to the hollow of her throat. Whenever I was afflicted by the general or Lady Qinglun’s cruelty, I would run to her. She would stretch out those withered hands and pull me into her arms.

“Little master, don’t cry. If they don’t like you, it doesn’t matter. Nanny loves you. Nanny cares for you.”

Even now I can see the scene. Nanny Zhang had planned to retire once I grew up. Although General Su treated me harshly, he was kind to his servants — he had prepared a house for Nanny Zhang and a yearly pension, even provisions for the funeral when the time came.

They had arranged a small courtyard for her while I was still there; I remembered where it was. I only hoped that when I came this time she would still be alive and would still remember me.

Her little house sat along a covered colonnade on Sishui Street. A pair of bronze rings hung at the door. I knocked; there was no answer for a long moment.

Pushing the door, I entered a neat private yard. A stone table and two benches sat in the courtyard. On one bench a woman sat, threading a needle in the sunlight.

“Don’t come back here.” She didn’t lift her head; her voice was a sandpaper rasp. “And even if I needed the money, I’d never do those things. Xiao Wu, go back. I don’t welcome you.”

A hot iron lodged in my throat and tears rose. “Nanny!” I called, my voice thin. The old woman froze, unable to believe her ears. The needle pricked her palm but she felt nothing.

“It’s the little master?” she asked.

“It’s me.” I moved quickly and took her hand. “Nanny, it’s me.”

“How could it be…” Tears welled in her eyes and her lips trembled. She cupped my face, fingers tracing my features as if to prove I was real. “I knew it. I knew you wouldn’t be gone. When you were born the lotus in our pond, which had been dead for years, bloomed like fire. From that moment I knew you were destined. I never believed the master when he said you’d died.”

I sobbed until I could not speak. She wiped my tears away. “Little master, you’re so thin. Have you suffered out there?”

I shook my head slowly. “None of that matters. Nanny, I missed you. All these years, I only thought of you.”

She held me and wept.

She led me inside. True to form, General Su had arranged a comfortable suite for her: three rooms on each side, a kitchen, and a privy. Nanny guided me to the main room and chattered about how the household had changed during the twelve years I’d been gone. I had little interest in the details, but out of respect I listened. When she asked about my life I didn’t expose the truth of the general’s lies; I told her I’d been bitten by a tiger and thrown from a cliff, saved by a farming family, and had lived with them since.

I smiled inwardly — “everyone” didn’t mean everyone; only she truly missed me. I didn’t say that, of course. Instead I invented a simple story: I’d hit my head again and only now regained my memory. It was plain enough that she did not pry.

“Come stay with me,” she insisted, seeing I had not visited in a while. “There are many spare rooms.”

That pleased me. I accepted and Nanny assigned me a room. I told her I was ill and needed to rest for seven days without visitors.

She readily agreed. I asked her to prepare seven days’ provisions, and she did. I begged privacy and she promised discretion.

Then the change arrived without warning.

It was a night without moonlight. I slept and was torn awake by a fierce, burning heat. Light flared through my lids; my bones felt like they were grinding together — crack, crack — muscles tearing, bones colliding. I felt like a soaked dishcloth being wrung: limbs grabbed and twisted hard. The pain lasted the whole night; sweat drenched the sheets. By dawn it steadied.

I felt my muscles rearrange. Half an hour twisting left, half an hour right — this truly was the “change”: torturous shifts and remakes. I bit my tongue so I wouldn’t scream; Nanny slept in the next room and I would not alarm her. Time passed and at last the pain ebbed. I rose, thirsty and weak, and walked for tea. My foot slipped when I tried on my shoes — they were too wide. A glance at my arms and wrists revealed they had thinned dramatically. The undergarment I’d slept in hung loose. I had gone from one shape into another overnight.

My master once said I had a fifty-percent chance of turning male and fifty percent of turning female. I had always hoped to become a whole man; the gods seemed amused and had sent me this smaller joke. But knowing it was only a coin toss steadied me.

I took tea and ate a little. Nanny knocked and offered porridge. Though I had warned her, she fussed. “No, Nanny, just give me a baked cake.” The moment the words left my mouth I regretted them: instead of my usual crisp boy’s voice, a fine, soft female voice answered.

“Nanny, does my voice sound strange? Have I caught a chill?”

“Ah — you kicked off your quilt last night and caught a draft!” I clapped a hand to my mouth and coughed, stifling it.

“Huh. Usually a chill makes one hoarse, not thin-voiced.” She frowned but didn’t press. She went out to prepare medicine, and half an hour later returned with a bitter broth. I forced it down. Though it tasted foul, her care made it feel like comfort.

During the change I was unbearably sleepy. After noon I lay down and dozed. Half-asleep, I heard a clear female voice at the gate and quick footsteps.

“Nanny! Nanny where are you?” a commanding tone called. “Second Miss, you here?”

They were talking in the courtyard. Nanny spoke quickly, and I realized it was the general’s second daughter, my only sister, Su Yue. Twelve years younger than me, she was now seventeen — headstrong, raised as a boy by General Su. I had little memory of her, but I did not want to meet her yet. I retreated to the bed, intending to wait until she left.

But in my haste I knocked against a table and a teacup lid slid and clattered. Su Yue’s voice shifted: “Aha — Nanny, why wouldn’t you come back? Someone’s hiding in the house. I must see who Nanny is hiding—”

Footsteps thundered down the corridor. Panic rose in me: Su Yue was approaching. With her sharp ears and Nanny’s fluster, I feared I would be discovered. I scrambled for the skylight — I could crawl out — but the window was too high. Yesterday I could have climbed it; now, transformed into a delicate woman, I could not.

Just as I stretched, feet still braced on the table, Su Yue kicked the door open.

Please sign in to leave a comment.