Chapter 19:

Chapter 19: The Prototype

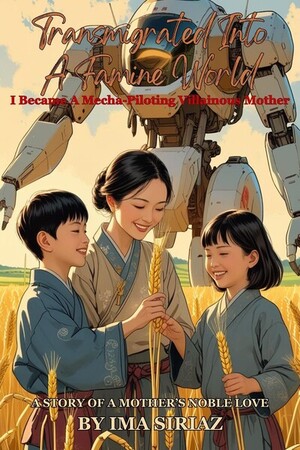

Transmigrated Into A Famine World, I Became A Mecha-piloting Villainous Mother

It was early morning in the sleepy town of Wyrmrest Hollow, twenty days after Darus Kael left. The villagers had continued on with their lives, cooking military rations in a late cauldron like before and going to work on the farm, with the meager water they had in the well. But on this very morning, everyone in the village woke up cursing. The reason was the noisy racket outside.

Outside, the loud sound of heavy metal running at full speed stomping the ground with its heavy feet reverberated throughout the village. For this very morning, Aina finally completed the construction of her own mecha. Not one she repaired by swapping parts. No, this was her own design.

Aina’s very own mecha, primitive by her own standards, but lightyears in advance compared to the mechas they had in this place. Sure she still used their parts, and the engine that she fitted into her mecha was their design, but everything else was her own!

Originally, Aina wanted to take the shortcut of just fixing the mecha in the best condition. But after running a manual diagnostic on the Gurn mechas. She realized that the shape itself was a problem. Besides, she couldn’t risk being seen running around with a Gurn machine. It could provoke misunderstandings. So she had to make a completely new frame.

Out of fear that the original owners would come and reclaim them, Aina had her sons help her scrape the paint off the mecha’s parts. She had also asked their sole blacksmith family to reforge some of the broken or bent metal parts, while the parts that couldn’t be made from scratch were replaced with wooden parts that their one carpenter family carved from the wood plentiful after the destruction of the village.

“Would you keep it quiet?!!” Aunt Soon yelled at Aina.

“Ha?” Aina replied, not really hearing her from inside the newly fitted cockpit.

Aina originally designed the cockpit to have a full glass canopy, unfortunately nobody in the village knew how to make glass. So she had to make do with fitting the Gurn mecha’s old cockpit in its place. She hated how their mecha had only three slits in front and one window on each side for vision. She could barely see anything in front of her and had to move her head around.

But she had no choice, so she made do with what she had. She vowed that once the soldier paid her repair fee in full, she would commission a full glass canopy. She could barely contain her excitement of striding around the fields in her own mecha, looking down like a goddess from twelve feet above.

“Stop this racket!” the others started yelling too.

“Be quiet!”

“I still want to sleep!”

Seeing that the other villagers wanted to say something to her, Aina stopped in front of them. She opened the side door just in time to hear someone yell at her from the ditch beside the road.

“I didn’t disturb your pooping, why would you disturb my pooping!”

“Who wants to disturb your pooping!” Aina yelled back before she closed the door again and went off on her merry go fun ride again.

Old Man Jine sighed. “Just let her do what she wants.”

“Aiya this girl, she always just does what she wants,” Old Jine’s wife complained but her lips formed a slight smile as she recalled a pleasant memory of her youth.

“I guess this means we should just start work early,” one of the villagers said.

“I’m already wide awake, might as well,” another villager agreed, going to his shed to pick up his farming tool.

The village certainly didn’t have many surviving farms left. Those farms that still fought for their lives were already struggling to survive with no water other than the occasional drizzle in the mornings. But they were still food, and with harvest only a couple of weeks away, it would be a waste not to be able to harvest what was left.

Just like how she had dreamed before, Aina happily rode a lap around the first mountain. Giddy like a schoolgirl, she laughed and giggled as the mecha ran at the top speed of 80 kilometers per hour. She wished she could open the cockpit and feel the wind on her face, but seeing the scenery flew behind her, she was content.

“This is greaaaaaat!” she yelled in her cockpit, aware that nobody could hear her.

When she finally had her fill of fun and excitement, she returned to the clearing behind her house, where a makeshift gantry assembled out of massive tree logs was constructed. It had less to do with feeling that she had enough, but more to do with anxiety. She had run two laps around the first mountain before she realized one fatal error in her design.

She didn’t know how much fuel she had left. Nor how much power she still had in her batteries.

The original Gurn designs were crude but brutally simple. They could operate directly off generator output alone, but the same couldn’t be said for her design. Every major servo cluster was paired with a mechanical assist to reduce peak electrical demand and smooth motion. Things like torsion springs, counterweights, and hydraulic dampers. But those assists only functioned properly when regulated through a stable, continuous power supply.

That was why she built the entire system around an electrical governor tied to a buffered battery bank, with the generator feeding into it. Without that buffer, the servos would desynchronize, the load-balancing would collapse, and the whole machine would seize up. No batteries, no walker

The locomotion architecture was another radical departure. The stock design relied on direct-motion mimicry. That meant the pilot moved their legs, and the strider’s leg actuators mirrored that input. It worked, but it was clumsy and exhausting, like running through molasses while strapped into a machine twice your size.

She scrapped it in favor of a drive-control system. What this meant was, going forward and reverse was done through a selector gear, the speed of which was governed by throttle pedal modulation. Slowing down was achieved by releasing the throttle and the braking was handled by a dynamic feedback in the form of the brake pedal. Basically, it was the control schema of a modern automobile. If one could drive a car, they could drive the mecha.

Except, of course, her mecha ran on a fully electronic drive-by-wire network rather than mechanical linkages

And then there was the gyro. The original design didn’t have a gyro, stability was maintained by the operator actively bending the legs so that they wouldn’t fall. Her design installed a powered flywheel gyro, a heavy rotor kept spinning by electricity, It fed stability into the body and movement the same way a bicycle wheel refuses to topple when it’s moving. It worked, but it was absurdly power-hungry.

She wanted something smarter. A mechanical gait regulator, a set of passive linkages and counterweights tied into the hip actuators. In her mind, it would act like a walking governor. Its every step would automatically swing the opposite hip, transfer weight, and lock the stance. No constant electrical draw would be required. But without precision bearings, custom cams, or hardened alloys, she couldn’t dream of building it.

So instead she was stuck with this primitive workaround. A gyro that guzzled current just to keep the frame from pitching sideways. The original designers solved stability with brute force, but it meant making the pilots so tired they couldn’t operate their mechas for more than a couple hours. Madness!

If she was a pilot on one of these mechanical nightmares, she would’ve probably quit her job within the first month.

Aina eased the mecha into position, settling it neatly between the gantry pylons before locking the joints in place. With a simple motion, she killed the engine with a twist of the key and popped open her side hatch. She climbed out carefully, climbed along the frame until she reached the engine assembly mounted behind the torso.

This wasn't the original design anymore, neither the appearance nor what was inside. The original strider carried its engine in a bulky housing that jutted above the shoulders, making the whole machine dangerously top-heavy and awkward to balance. Aina had overhauled that flaw completely. She had shifted the powerplant down into the torso itself, redistributing the mass across the frame. The result was a lower center of gravity, a more compact profile, and a machine that no longer staggered like a drunk giant with every step.

The air intake was placed lower down the back, opening to the sides. Naturally, the exhaust pipe was also placed lower, but still pointed upward. Unlike the original designs, Aina made both the air intake and exhaust pipe more discrete, reminiscent of the common sleek mecha designs in her old world.

She flipped open the fuel port and leaned over, peering inside with a faint frown. The tank was still more than half full, which was reassuring, but the process itself felt irritatingly primitive. Squinting into a hole with no gauge, no sensor, and no readout was as unreliable as it was tiresome, especially for something as critical as fuel. Shaking her head, she snapped the cap shut and made her way back around to the front of the torso.

There, tucked beneath the twin spotlights, she unlatched a pair of service compartments. From within, she drew out one of her improvised diagnostic tools: a simple wire rig ending in a bare lightbulb. Crude, yes, but effective. She clipped its leads onto the anode and cathode of the battery banks, then watched carefully as the filament glowed. It wasn’t a proper voltmeter by any means, but it told her enough. In this world, with no proper instruments at hand, she had to make do with whatever she could fashion.

She was relieved to see the filament flare with a strong, steady glow. It meant the charge was still healthy, at least by her improvised standards. After that quick check, she moved on to the batteries themselves, carefully removing the inspection caps to peer inside each cell. The electrolyte level was right where it should be, neither too low nor bubbling over, and that gave her some measure of reassurance. Satisfied, she sealed the caps and latched the panel shut before turning to the other compartment.

This second bay held another cluster of three lead-acid units strapped together in parallel, identical to the first. She thought of them in simple, practical terms: Battery Bank 1 and Battery Bank 2. Crude names, but it suited its purpose. Both were wired for 24 volts, sturdy enough to drive the actuators as long as the generator kept feeding them.

With both banks operating correctly, she could, in theory, keep the strider moving under reserve battery power alone for a good half hour, provided she kept it to walking speed. But the margin was thin. If one battery bank failed or had to be disconnected, that window of operation would be cut neatly in half, and every minute of endurance shaved away would weigh heavily on her decisions in the field

That wasn’t much time at all, but Aina had no choice. She couldn’t manufacture her own battery. If she could, she would’ve made a better version. The only reason she even knew how to use this fossil was because she grew up helping her uncle fix cars. Most people of her generation didn’t even know this kind of battery needed regular refilling with distilled water.

Once Aina was finally back on the ground, she took a piece of broken wood and made a list of the things she needed to do with a piece of white chalk. She noted that the fuel indicators could be outsourced to their resident blacksmith while the battery capacity indicator wasn’t particularly important at the moment. She underlined the last task before going back to the former chief’s mansion for breakfast.

The last thing on the list was “dig a well”.

Please sign in to leave a comment.