Chapter 0:

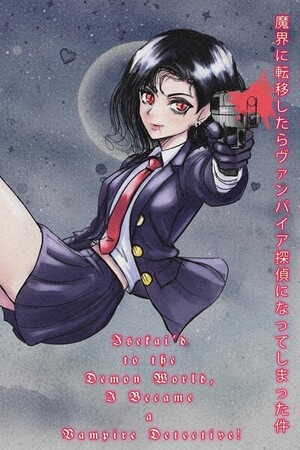

Mei-Ling

Isekai'd to the Demon World, I Became a Vampire Detective!

I could do naught as an overwhelming trepidation took hold of my frame. My knees gave way, and I fell as though struck by an unseen hand, cast aside by a force so insurmountable as it was to hold the tremendous force of ten trillion suns’ light, all advancing toward the desolate landscape I now called my home.

Floating before me, draped in the sable vestments of a nun—whether woven of shadow or taken from some forgotten sacristy, I could not say—she appeared like a dreadful icon suspended high in the dark ink-black sky. This was the indomitable spirit that haunted my waking hours: Cleodiana, the lady whom they named empress of the quantum. It was as if our very idea of providence were a child’s sweet dream, from which we were roused into the abyssal and waking nightmare of the world as it truly is.

I saw the slender pupil of her eye, a dark line drawn through a sea of burning crimson; the spectral pallor of her skin, and the strange lustre of her teeth as her arm drew back as if in answer to some unspoken challenge. It took but a moment more for the sky to fade from its miasmic twilight. The strange gave way to the wholly unreal, for I could not readily credit the unfettered spectacle of the Empress’s power, so terribly displayed.

In this, the bleakest of all moments, my mind is drawn back, as if by some dreadful and irresistible influence, to the very hour that marked the beginning of my misfortune. I find myself questioning whether any event in a woman’s life may be called by coincidence, or if my destiny, with an intelligence all its own, had not always heralded me through time and space to this final, unquestionable end.

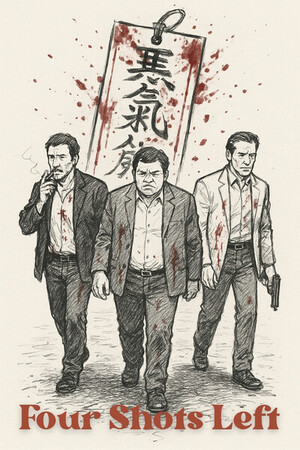

I was, at that time, but a detective with the Hong Kong police, and of no special note. It was therefore with a profound sense of dislocation that I was summoned by my superiors. My family, they had somehow learned, descended from a long line of Taoist priestesses, and for reasons I could not then surmise, the government perceived this spiritual lineage as a matter of chief importance to be accounted for.

The chief’s office was a sterile place, quite void of any personal touch, possessing the impersonal air of a stage arranged for some grim and fleeting drama. His voice, with a pointed insistence, penetrated the reverie wherein I had lost myself, seated upon a stiff and unforgiving wooden chair.

“Under the scrutiny of internal affairs, the bureau should find it within everyone’s best interest to welcome your new partner, Mary Winters.”

The foreign name caught me off-guard, and sooner still, my eyes widened as the slender frame of a blonde woman swayed in, as if she were a viper lying in wait. It was difficult to tell if she were European or American, though my mind settled upon the latter at the sight of her jeans—a conclusion born, perhaps, of mere intuition. Her shoulder-length hair seemed to float for a moment before she leaned against a filing cabinet, her white blouse hanging loosely in a half-tuck.

Her lips were stained red with the brightest of lipsticks against her pale skin, and for a moment, I confess I felt my heart flutter with a strange and unwelcome apprehension. I knew then that my Taoist lineage, in this growing age of scientific skepticism, was being treated as some grim, operational consequence by the government, and that this squalid measure was for their benefit rather than mine.

The woman—Winters—pushed herself from the cabinet with a languid grace that seemed to contradict the sharp modernity of her attire. Her voice, when at last it came, was not at all what I had anticipated. It possessed a low, clear timbre, with an unfamiliar accent. I could not begin to recall what may have been said.

The chief, however, did not wait for a reply, but turned to some papers on his desk in a gesture of final dismissal. And so I was left, in that oppressive heat, under the steady, analytical gaze of the woman with the deceptively simple name and the aspect of a patient predator.

The weeks that followed our strange introduction unfolded with a monotonous languor, punctuated only by the disquieting industry of my new partner. For Mary had begun a series of inquiries into my life, a process conducted with such a quiet and relentless precision that I felt my past being dissected before her. It would have been in my best interest, I am sure, to say naught; and yet, I found myself, against my better judgment, making a confession. I told her that I had, in my younger teens, studied to become a Taoist priestess, but that the world’s demands for financial security had seen fit to steer me from that path. I could not ascertain whether the small and fleeting quirk of her lips was a smirk of amusement or a scoff of dismissal, but the sight of it upon her blood-red mouth filled me with a singular and immense displeasure.

Our post was a small police box in Kowloon, a lonely sentry overlooking the dark and indifferent waters of the harbour. It was in this place that the true nature of my demotion became most apparent, for we were given tasks of such… absurd triviality. I felt a great listlessness settle upon my spirit in those days, though perhaps I ought not to have minded. For what is it to return a lost child to his home, or to rescue some poor kitten from a precarious perch? They are duties as important as any other, I told myself.

This dreary state of affairs persisted until one evening, as the weekend was drawing to its close and the sky was painted with the colours of twilight. A frantic and dishevelled older woman appeared before us, her words tumbling out in a torrent of alarm. Someone, she claimed, had been stealing the animals from her small neighbourhood petting zoo. By all rational measures, it was a matter of deep absurdity; and yet I knew, with a certainty that chilled me, that this trivial, almost childish affair was to be the great and singular case of our unfortunate partnership.

You may call it a peculiar vagary of my Taoist mind, but the mundane motivations which Mary proposed for these strange thefts eluded me entirely. She spoke of animal traffickers, of local miscreant mulligan mixers engaged in some cruel mischief, and whilst I knew it was entirely possible that I was mistaken, my intuition suggested a cause of a far stranger and more sinister character. And yet, as I could offer no tangible hypothesis of my own, I conceded to her proposal of an old-fashioned stake out.

The nights that followed were possessed of a weighty silence, a chasm that stretched between Mary and myself in the close confines of our watch. I was dubious that any true efficacy could arise from our partnership, so stark was the difference in our natures. My mind, at first a tumult of resentful thoughts, found itself gradually soothed by the deep and hypnotic stillness of the late hours, until I was lulled into a state of hazy comfort. It was then, from this place of tranquility, that they appeared. A group of figures, cloaked in the grim, ascetic robes of some unknown order, materialized from the shadows of the petting zoo.

A gasp, sharp and sudden, was all I could command, for the sight had arrested the very breath in my lungs. Mary, however, betrayed no such hesitation. She sprang into motion with a swift and silent grace, maneuvering to the shadow of an adjacent tree, whence she might observe them better under the pale disclosure of the moon.

I found myself taken aback by the unnatural fluidity that governed her every motion. She stalked the periphery of the scene below, possessing the predatory grace of a panther of the night, and I had the distinct impression that her very nails were drawn and ready to strike. From the dark there came a single, pitiable bleat from one of the lambs, followed by a silence so abrupt and strange that it seemed to swallow the sound whole. Was the poor creature's life already forfeit? The darkness was too complete to be certain, but in the next moment, two of the figures emerged, bearing the lamb between them, its form limp and unresisting as they passed through the gate and toward the alley.

A great lump formed in my throat, which I swallowed with some difficulty. I made my own descent from the rooftop, a clumsy and graceless affair, in stark contrast to the movements of my partner. When my feet at last found the ground, I saw that the place where she had stood was entirely vacant; she had vanished into the gloom as if she had never been. A terrible sense of hopelessness fell upon me, for I was utterly alone, and the trail, I believed, was lost. It was only as I hastened from the soft grass onto the glittering concrete of the sidewalk that I caught it—a mere flicker in my periphery—the trailing hem of a dark robe disappearing into the maw of a neighbouring alleyway.

As I sprinted across the way, I stopped suddenly, my eyes peeking from around the corner. I could see no sight of Mary, only the meanderings of the group as they turned inward, as though they were entering the deep confines of a shanty maze. I prepared my step in quiet, but the sudden bang from behind cause me to stumble forward and fall.

My pursuit was arrested by a sudden, acute clatter from the shadows beside me. A small, black kitten, its form a blot of ink against the somberness, had dislodged the lid of some refuse bin. It looked upon me with eyes that shone with a pale, green light and issued a thin, plaintive cry—a sound that seemed less a plea for comfort and more a forlorn warning.

For a moment I hesitated, my gaze shifting back toward the alley. The robed figures were gone, having been entirely swallowed by the darkness. I knew, with a sense of fatalistic certainty, that I must follow.

Please sign in to leave a comment.