Chapter 2:

A Strange New World

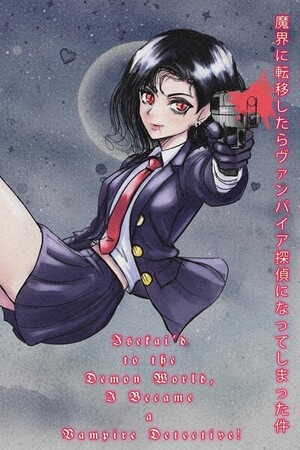

Isekai'd to the Demon World, I Became a Vampire Detective!

For how long I drifted in that place, I cannot say. Time had no purchase there, and my thoughts were a tormenting carousel of phantasms: the image of Mary, pale and wounded; the sight of those cowled, unholy figures; and the dreadful, recurring question of what strange and terrible shore I had been cast upon.

The land itself was a desert of some forgotten hell, stretching in every direction under that starless, black firmament. The ground was not sand, but a fine, crimson dust, the colour of dried blood or powdered rust. My rational mind, what little of it remained, sought some earthly explanation for such a colour, that perhaps it was like the Martian regolith of iron oxide deposits. It seemed not a natural soil, but a ground perpetually stained, as if by some colossal haemorrhage.

The desert stretched before me, a panorama of measureless desolation, its quiet a palpable vacuum. The crimson dust, fine as powdered pigment, formed vast, rolling dunes that rose and fell with a dreadful softness, like the slumbering bodies of colossal and long-dead things. There was no sun in the black skies above, nor any moon or star, yet the landscape was illuminated by a faint, sourceless luminescence—a pale, phosphorescent glow that seemed to emanate from the very dust at my feet, casting no discernible shadow.

Here and there, the monotony of the rust-coloured expanse was broken by jagged shards of black, vitreous rock that jutted from the ground like the broken teeth of some subterranean beast. The air itself was thin and without scent, as if I were breathing the dust of aeons. It was a place of deathly stillness, neither hot nor cold, but possessed of a strange, neutral temperature that offered no comfort and spoke of an utter absence of life.

At times, a wind would stir, though I could not feel it upon my skin. It would move across the dunes not with a with a low, sibilant whisper, disturbing the crimson dust into slow, spiraling patterns. There was no other sound. It was a sepulchral silence, so complete and so heavy that it seemed to press upon the ears—it was… a palpable presence in itself. It was a geography of despair, a place so utterly alien and empty that it felt not so much like a world…

The terrible calmness of the place began to work upon my nerves, and the stupor of my arrival gave way to anger. My mind replayed, with a tormenting clarity, the events in that haunted room: the sight of Mary, so cruelly struck down; the solemn, unholy industry of those cowled figures; and my own dreadful impotence in the face of their ritual. A bitter and insolent rage rose in me then, and I began to walk, with no destination in mind save to put one foot before the other, as if the sheer act of movement could quell the tempest in my mind.

It was in the course of this desperate pilgrimage that I began to notice a change in the landscape. The shards of black, vitreous rock, heretofore mere sporadic interruptions in the orange-crimson dust, grew more frequent. At first they were but scattered splinters of solidified night, but soon they appeared in clusters, their dark forms seeming to drink the faint, sourceless light. A pattern began to emerge, a trail of sorts, and I found myself following it, my rage giving way to a strange and fearful curiosity.

The black crystals grew thicker still, coalescing until they formed a veritable river of jagged, glassy stone, which led my eye to its source: a dark maw in the face of a low, wind-scoured cliff. It was a cave, its entrance flanked by the largest of the black shards, standing like grim and silent watchtowers before a gateway into the unknown.

Some force, whether born of my own desperation or some more subtle influence, compelled me across the threshold. The interior was not dark as I had expected, but alive with a cold and silent fire. The faint, phosphorescent glow from the desert outside seemed to be captured and amplified by the countless black crystals embedded in the walls, refracting into a thousand ghostly hues that danced upon the rock.

I had taken but a dozen paces when I perceived a significant change in my surroundings. The path began a gentle, spiraling descent, and the crude, natural rock of the cave gave way to walls of hewn stone. They were fitted together in a mosaic of breathtaking and unsettling precision, polished to a gloss that mirrored the fractured array of light. The beauty of the place was of a kind I had never imagined, yet it offered no comfort, for I knew then that I was not in a natural cavern, but in a place of artifice and design. I was treading the halls of some vast and unknown sepulchre.

I proceeded deeper into the sepulchre, my footsteps making no sound upon the polished stone. The path continued its gentle, spiraling descent, and I was overcome by a strange reverie of dread and wonder. This trance was broken when the grand hallway opened abruptly onto a precipice. Before me lay a chasm, a sheer and fathomless fissure in the mosaic floor, across which stretched a narrow causeway of the same black, polished stone, unsupported by any pillar or chain.

With my heart aflutter in my chest, I set foot upon this perilous bridge. The stone was unnaturally slick, as if coated in a thin, invisible film of moisture. My footing gave way without warning, and with a small cry of despair that was swallowed by the immense silence, I was pitched headlong into the darkness below.

The fall was not a violent tumble, but a long and strangely tranquil descent through an endless void, and a peculiar calm settled over me—the calm of one for whom all hope is lost. I did not strike rock as I had expected, but was received instead by the cold, silken embrace of still, black water.

I surfaced, gasping, in the center of a vast, subterranean lake. And as my eyes adjusted to the faint light that filtered down from the chasm far above, I beheld a sight that arrested my weary breath. I was in a cavern of impossible scale, its ceiling lost in the high darkness. All around the lake's shore, carved from the living rock of the cavern itself, stood a silent city of colossal statuary and towering pillars, sculpted in the likenesses of gods and monstrous, alien royalty. I had fallen through the floor of a tomb, only to land in the sunken metropolis of some long-dead and unholy society.

Or so I had, in the first shock of my arrival, supposed. My initial impression was of a place of immense and sorrowful antiquity, a city drowned and long dead. Yet, as I drew myself from the chill of the lake onto a wide, brick-laid shore, a different and more unsettling perception began to take root. The colossal statuary and towering pillars were not worn by time; their lines were too clean, their surfaces too pristine. There was no dust of ages here, no sign of the gentle ruin that ought to have claimed such a place.

The bricks beneath my hands were of a colour I could not name—a deep and lustrous violet, almost purple, that seemed to absorb the faint light from above. A channel had been cut into these strange brickways, through which a river of the same black water flowed with a silent, deliberate purpose. And nearby, I could hear the constant, musical hiss of a waterfall, its source hidden in the dire, dire, gloom.

I stood, shivering, and gathered the great, wet mass of my long, black hair, wringing the cold water from it. The small, physical act was a frail anchor in a sea of unreality. For this place was not a ruin. It was not dead. Its impossible cleanliness and the steady, managed flow of its waterways spoke more of… of maintenance. And a dreadful certainty crept upon me then, cold and piercing as the water from which I had just emerged: I was not, and had never been, truly alone.

I began to walk along the bank of that silent, channeled river, rubbing my arms against a rampaging chill. It was then that I heard it—a faint and rapid flutter, like the beating of a moth's wings close to my ear. Before I could turn my head, a pain, sharp and sudden as a needle's prick, pierced the flesh of my neck.

I raised my hand in a convulsive motion, but met only empty air before slapping the nape of my neck. I drew my fingers away and saw upon them, with a sense of profound unreality, a mess of blood splattered across my palm.

A strange languor began to creep upon my limbs, a leaden weariness that seemed to rise from the very site of the wound. The hard, clean lines of the foreign city began to soften and swim before my eyes, the world dissolving into a haze of violet and black. My head turned, as if of its own accord, toward a dull report, like a distant gunshot, that had sounded from somewhere in the haze to my side. I squinted, my failing vision struggling to resolve the image, and beheld a scene of terrible and inexplicable violence. In the distance—though the very concept of distance seemed to have lost its meaning—I perceived a figure: a girl with hair like spun silver, her hands clawing at her own throat as if to tear away some invisible restraint.

From a bottomless darkness, my consciousness struggled back to the surface, as a drowning woman fights for air. My last coherent thought was of that terrible vision—the silver-haired girl in her silent agony—before the cold, black water of the lake had closed over my head, and all was extinguished.

Please sign in to leave a comment.