Chapter 8:

Melancholy in D Minor

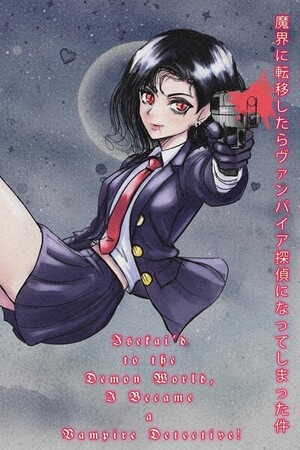

Isekai'd to the Demon World, I Became a Vampire Detective!

The descent was blessedly brief. I landed not with a crash, but with a soft thud upon a great mound of what felt to be velvet. The air in this place was heavy, freighted with the incongruous scents of ozone and some strange, funereal flower. The chamber itself was lit by the gentle effulgence of a million shimmering motes of dust, which drifted through the air like a captive galaxy.

As my eyes grew accustomed to the strange light, I saw that I was in a vast, domed chamber, a forgotten space at the very apex of one of the old, lilac-hued edifices. Great lengths of purloined silk and shimmering brocade were draped from the high rafters, hanging like the vines of some colourful and artificial flora. Piles of soft matter—more fabrics, mosses, and the cast-off plumage of some exotic bird—were arranged into what appeared to be small nests, and scattered all about was a glittering detritus, the hoard of a great magpie: lost jewels, polished stones, and fragments of coloured glass.

My quarry stood in the center of the room, holding the length of midnight-blue silk she had stolen from the angel. But she was not looking at me. Her eyes, however, were not upon me; rather, her gaze was transfixed by some unseen thing in the vacant air before her. The stolen silk was held aloft, not in the manner of a trophy, but as a votive offering to some invisible power.

A sudden, unnatural chill filled the chamber. The glowing dust began to swirl and gather in several points, coalescing into faint, humanoid shapes. At first they were mere suggestions, translucent and indistinct, but in moments they resolved into the forms of several young women, their skin possessing a pale, bluish cast. They were semi-corporeal, their edges blurring into the dust-filled air…

One clutched a rusted, spectral flail and shield, while another held a long, thin blade that seemed to weep darkness. The pixie, so far as my eyes could tell me what the thief was, offered the silk to these phantoms, who regarded it with an empty indifference. The focus of the chamber shifted. It was not a turning of heads, but a sudden and uniform pressurization of the silence around me, which seemed to contract upon the jarring fact of my living heart.

The only sound to pierce it was the thin, needle-like chittering of the little thief who stood at its center.

My hand, concealed within the pocket of my new coat, found the cold, hard grip of my pistol. Its familiar form was a comfort at once useless and yet essential—a secret anchor in this phantasmagorical sea. Affecting a calm I was far from possessing, I moved with a studied slowness, leaning a shoulder against a great pile of dusty velvet as if I were but a disinterested spectator at some minor theatrical. Though my heart beat a frantic tattoo against cartilage, I commanded my features to remain a mask of impassive neutrality.

One of the spirits, whose pale, bluish form seemed more defined than the others, began to drift forward from the group. She held in her translucent hands the ghostly suggestion of a violin and bow, and as she moved, a faint and mournful melody, impossibly sad, seemed to emanate from the very air around her.

She did not halt in her advance until her face was but a finger's-breadth from my own, so near that I could feel a profound and sepulchral cold emanating from her very substance. Her head inclined, and a slow, beautiful, yet altogether terrifying smile bloomed upon her apparitional lips. I understood her purpose then; it was a trial, the cool assessment of a hunter taking the measure of a strange new quarry. I answered the snowy blue glow of her eyes with an unblinking stare, refusing to grant her the tribute of my fear.

Her voice, when it came, was not a voice at all, but a melodic whisper that sounded like the sigh of strings. "Such... vibrant colours," she breathed, her hollow eyes seeming to look not at me, but into me. "It has been so long since we have seen such light."

Her words were nonsense, a poetical madness that had no place in a moment of such tension. Colours? Light? I could not fathom her meaning. But I understood the slow, terrible smile on her spectral lips. I understood the soul-deep cold that radiated from her form, and the undisguised hunger in her seemingly empty eyes. This creature, whatever her… strange words meant, intended me great harm.

Her smile remained fixed, unwavering. At this, as if upon some silent signal, the other phantoms began to drift forward from their silken bowers, forming a silent and ever-tightening circle about me. The Violin Banshee then raised her diaphanous hand, her fingers extending not toward my throat in an act of violence, but toward my brow, as if to begin the performance of some strange and terrible rite.

There was nothing to say, no logic that could apply here. Cornered, with multiple hostiles advancing, my training took over where reason had failed. In a single, fluid motion, I drew my pistol from my pocket, the heavy, solid weight of it a stark and direful absurdity in my hand. I aimed the barrel at the heart of the smiling phantom.

My police training was a thing of pure reflex. I did not hesitate.

The report of the pistol was a deafening and profane thunderclap, rupturing the amniotic quiet of the orrery. The weapon bucked in my hand, a brutal but welcome anchor to the world I knew. The acrid smoke that followed, an odour I associated with order and consequence, soon fouled the delicate, clockwork air.

The leaden bullet struck the banshee square in the chest. Her form did not bleed, but erupted in a quiet explosion of shimmering, blue-tinged dust, the same motes that filled the air. The mournful violin melody ceased abruptly, and the other phantoms seemed to recoil, their forms wavering. For a single, glorious heartbeat, I felt a surge of triumph. My world, my rules, had asserted themselves.

But the dust did not truly settle.

It hung in the air for a single, pregnant moment before the particles began to reverse their course, drawn back together by some unseen and terrible gravity. The mournful violin melody, which had been silenced, began to play anew—a low and mocking tune. The dust swirled and knitted itself back into the shape of the smiling phantom, her form as solid and serene as it had been before. She looked down at her chest, where the bullet had passed through, with an expression of mild curiosity, as if inspecting a minor tear in a garment.

Her dead eyes then rose to meet mine, and her beautiful, terrifying smile widened.

"'How... crude," she whispered, her melodic voice laced with a boreal and sidereal amusement. "And how... very, very bright."

The pistol in my hand felt suddenly impossibly heavy, a useless lump of cold iron. I had fired my only strategy, revealed my final hand, and all I had accomplished was to ring the dinner bell.

Her amusement, it seemed, was at an end, for she resumed her silent, forward drift. Her translucent fingers, from which all living heat had long since been scoured, alighted upon my forehead with a terrible gentleness.

The world dissolved. It was not a physical sensation, but a psychic one—a terrible, invasive pulling, as if a needle were being threaded through my very consciousness. In that instant, a memory flashed, unbidden, across my mind's eye: the serene, angelic face of the Lady Seraphina, her own fingers resting in this very spot. She had read me. This creature was doing the same, but its touch was not a gentle reading as its touch; it was a hungry, tearing consumption.

No.

The thought that rose in answer was not one of words, but a primal and defiant roar that echoed through the landscape of my mind. I would not be a mere book for this monster to peruse at her leisure and then cast aside. I marshaled all my will, focusing it upon the memory she attempted to excise—a sun-drenched afternoon, a street in Hong Kong—and held it fast, throwing the entire force of my own spirit against her terrible intrusion.

I was suddenly unmoored, adrift in a non-corporeal space where the laws of the world held no dominion. Her form was a flickering, uncertain thing, at once everywhere and nowhere. From all sides came her melodic laughter, a sound full of a cruel mirth, intended to disorient the mind and force me to relinquish my hold. She would coalesce before me, smiling, only to dissipate into motes of light as I tried to focus; then I would feel her touch grazing my neck, a chill that was not of temperature, but of a feeling like the slow trailing of a dead and desiccated leaf.

But in her cruel game of shadows, I began to divine a certain rhythm, a cadence to her taunting manifestations. It was the faintest of intuitions—the mere ghost of a guess. When she flickered into view to my left, her mouth open in a silent, mocking laugh, I did not fix my gaze upon the apparition itself, but rather upon the empty air just ahead of it; the place where the veil between worlds seemed at its most fragile, where the next beat of her terrible rhythm must surely fall.

I struck out, not with my arm of flesh, but with the focused totality of my will. The impact was a jolt that was at once of the mind and yet possessed of a shocking and impossible solidity, and I was sensible of the ghastly sensation of her phantasmal cartilage giving way beneath the force of it.

The psychic connection shattered. The banshee was hurled backward to collapse amongst a pile of stolen silks, giving voice to a thin shriek of outrage and pain. In that same instant, the air in the orrery seemed to thin and solidify, growing sharp and heavy, as if the space had been filled with finely powdered glass. An unholy fire, the lime colour of a gas flame, then began to crawl upon the walls, and in its flickering, blue-black light, the shadows of the hanging fabrics writhed and danced like hanged women.

The banshee rose to her feet, her serene and beautiful face now twisted into a mask of pure, murderous rage. The air crackled with a power that made the hair on my arms stand on end. A tremor of pure, animal fear ran through me, but I did not let it take root. Instead, I fell back on a different kind of memory, a different kind of magic, drawn from the flickering screen of a childhood movie theater.

My body settled into a low, defensive crouch. I raised my hands, two fingers extended, my thumb holding the others down—the classic, unwavering stance of the Taoist jiangshi hunter, Mr. Lam. Useless folklore against a real ghost, perhaps, but in that moment, it was all I had.

The banshee's shriek of fury was a command. As one, the spirits lunged. A warrior phantom swung its ghostly flail, which passed through a pile of silk, leaving a trail of frost in its wake. Before my conscious mind could even register the threat, my body moved, twisting and diving with a speed that felt… exotic. I found myself on the other side of the chamber, my back against the far wall, with no memory of having crossed the intervening space. A disorienting sense of vertigo washed over me—a disconnect between what my mind knew to be possible and what my body had just done.

I did not fight them, but rather moved between them, a fluid shadow in the flickering blue fire. This new body, which I had considered a clumsy prison, was now revealed to be a thing of impossible grace, responding to threats an instant before my mind could apprehend them. The fear persisted, a tightly wound spring of iron in my viscera, yet it was now accompanied by a new and terrible calm. My body acted, and my mind, for the first time, became a mere spectator… to its own vessel's strange performance.

My evasion, however, could not be eternal. The banshee, her fury lending her a terrible new speed, finally cornered me against a wall of brocades and jacquards. Her fingers, things of no true substance, closed around my arm, and their touch sent a paralytic stasis through my veins, a stillness that threatened to drain the very life from my being. The pistol in my pocket seemed a meaningless trinket. My mind screamed its denial, but a more primordial part of my being, a thing born in that violet sewer, rose to the fore and took dominion.

The new and darker part of me asserted itself with a sudden violence. I lunged, my head dropping, and with a savage impulse I did not recognize as my own, I set my teeth into the incorporeal limb that imprisoned me.

The sensation was a shock—not the iorn-laced tang of mortal blood, but a poignant, resonant taste, like petrichor without rain. The banshee gave a shriek of pure, violated agony and recoiled as if from a white-hot brand, her form flickering with a terrible violence.

I stumbled back, my heart pounding a frantic rhythm. A thick, dark blue fluid, glowing with a faint internal light, dripped from my fangs and stained my lips. It was the blood of a ghost, and I had just tasted it.

For a single heartbeat, the shock of my own monstrous act held me in a moment of stunned paralysis, the strange, resonant taste of the phantasmal ichor still upon my tongue. But this was swiftly supplanted by a sensation far more terrible: a vast and insatiable craving. The fire of the conflict, the impossible grace of my limbs, and now this… this new and ravenous famishment of the soul eclipsed all other thought, all other feeling.

My perception of the room shifted. The spirits were no longer a jury of the dead, but a banquet laid out before me. With a slow and terrible deliberation, I licked the luminous, cerulean ichor from my lips. The flavour was a strange music on the tongue—the resonant vibration of a broken violin string and shattered ivory—and it was the most exquisite thing I had ever known. Every instinct I now possessed was fixed upon the source of that grieving, perfect taste.

I saw the Violin Banshee cradling her wounded arm, her beautiful face contorted with a look of pure, disgusted horror. The other phantoms, who had seemed so menacing moments before, now recoiled, their forms flickering with an unmistakable and delicious fear.

A low, predatory energy began to thrum through me. My body coiled, shifting from foot to foot in a silent, bouncing rhythm of anticipation. I did not think. I did not plan. I simply pounced.

I precipitated myself across the rotunda, moving not as a woman of flesh, but as a silent and dreaded shadow. My target, a phantom of martial aspect bearing a flail of solidified light, was far too slow. We collided, tumbling to the floor in a chaotic swirl of blue flame and dark cloth. Its being, though seemingly incorporeal, had about it a strange and definite heft.

Seeing their sister helpless in my grip, her poltergiest sisters surged forward in a silent, vengeful wave. The Violin Banshee, her countenance a mask of glacial fury, raised her instrument as it coalesced into form. It became, for a moment, a thing of solid, ethereal wood, and she swung it against my head with a sickening crack. The blow exploded in a shriek of discordant music, and its force sent me tumbling, releasing my quarry with a tear of ectoplasmic flesh.

A dull, painless thud echoed in my skull, and the world tilted for a moment, but the searing pain I expected never came. It was like being struck with a child's toy. I rose slowly, deliberately, to my feet and rolled my head on my shoulders, producing a series of loud, satisfying cracks from my neck.

The action of the impact was a distant thing, a mere echo against the terrible new craving that now governed me. My body, now a vessel for this purpose, took a single, inexorable step forward.

The effect was immediate. The spirits, who had been pressing their attack, all floated back as one, a collective gasp of fear rippling through their forms. I could feel it—their terror—a frigid, delicious scent in the air.

The hunger was still there, a roaring fire in my soul, but through it, the detective surfaced. I licked a final, glowing blue trace of ectoplasm from my lips. "Now," I said, my voice a low and dangerous purr I did not recognize as my own. "Tell me why you are stealing."

The phantoms wavered, their empty eyes wide with a new kind of fear, but before any could stutter a reply, a high-pitched chittering sound cut through the air. The minuscule, winged form of the pixie zipped between us, hovering defiantly in the space between myself and the ghosts.

"Don't!" she shrieked, her voice a high-pitched, twittering thing, filled with a desperate and trembling panic. "Please, don't hurt them anymore!"

She spread her shimmering, insectile wings and tiny arms wide, positioning her body between me and the cowering phantoms. "It was I who stole the fabric! Not them! If you seek to punish someone, then punish me!"

At her words, the forms of the banshee and her sisters, woven of dust and light, seemed to lose their coherence. They exchanged looks of strange and sorrowful confusion amongst themselves, and the entire aspect of the conflict was altered. The predators were revealed as frightened sheep, and the tiny pixie their shepherd. A single brow rose upon my forehead in an expression of pure, inquisitive surprise.

I let the silence stretch for a long moment, my gaze shifting from the terrified spirits to the defiant pixie. The predatory hunger still coiled in my gut, but the detective's need for answers was now ascendant.

"Why?" I asked, the single word cutting through the quiet of the chamber with the sharp, clean finality of a closing cell door.

The pixie stared at me, her defiance flickering in the face of my cold question. For a moment, I thought she would lunge again, but instead, a strange, almost pathetic sound escaped her, half a sob and half a bitter laugh.

"A fix?" she repeated, her voice a sharp, ragged whisper. "Do you have any idea what it's like? To be... an echo? You can't taste anything. You can't feel the stars or the wind. It's just... grey. Silent and forever."

Her explanation was offered as a plea, directed toward a capacity for sympathy that had been scoured from my mind. The predatory calm that now possessed me was a wall against her sorrow. I paid her words no heed, my gaze possessing all the dull, impassive weight of polished lead.

"So you steal from the angel," I stated. It was not a question, but an accusation.

My refusal to engage with her pain seemed to startle her more than my violence had. "She's the only one who has it!" she shrieked, pointing a trembling finger in what I could only assume was the vague direction of Seraphina's boutique. "The only one who weaves with real Starlight! You think this is just about being bored?"

The kimono-clad onryou with wild eyes darted to the bolt of silk on the floor. "When we unravel her weave... we can feel it. The cold, the heat, the jolt... everything. The girls... they get solid enough to enjoy things again." A manic grin touched her lips. "And the power... for a little while, we're not just ghosts hiding in a dome. We're strong."

She looked back at me, her desperation raw and ugly. "You wouldn't get it. We need that feeling. We'd do anything for it."

And so, I understood.

Not survival. Sensation. A desperate thirst to feel a flicker of warmth in their cold, dead hearts. A motive born of an eternal, grey boredom. How... pitiable. And in a strange and terrible way, how succintly familiar. The hunger was the same, but theirs was a crude and clumsy craving. Mine was becoming something... purer.

A thought occurred to me then, a simple and obvious question. I looked past the pixie to the wounded banshee, then back again. "This... Starlight," I said, my voice quiet. "It comes from the angel's weave. Why steal the cloth? Why not simply take the light directly from the source?"

The pixie stared at me as if I had suggested we might drink the Sun. A manic, broken laugh escaped her. "Take it from the stars?" she shrieked, gesturing wildly. "Only a celestial can handle raw Starlight! She weaves it, she tames it. For anyone else, to touch the source... the raw potency of the energy would burn a thing like me to ash. It would unravel them completely."

Her voice dropped, full of a terrible craving. "The cloth is the only way. The only way we can get a taste."

Her words settled into the quiet of the sanctum, yet I remained puzzled as to why this creature would require the congress of such phantoms. “But you, of all creatures here, are no ghost,” I observed, my tone laced with a vitreous contempt.

The pixie recoiled. “I might yet be, upon some finer day!”

A look of visceral disgust curled my lip. “And yet, you covet the sensations of the spectral, yet lament their function?”

The pixie could only look away.

“For you to already feel such things,” I began, “then it must be—”

“It is a pleasure,” she admitted, and the final, terrible component of the mechanism became clear. I understood at last their pathetic cycle of theft and sensation. I had tasted it myself—that resonant taste of cold burning fire singing upon my tongue. A part of me, the new and monstrous part, craved more; but the older part, the detective from Hong Kong, was filled with an unutterable disgust.

I looked down at my own hand, clenching it into a fist and then snapping it open. The sound of my knuckles cracking echoed in the chamber like gunshots, a sharp report of aggression. My eyes widened slightly as I felt the effortless, terrible power coiled in my own muscles, a power I would now use for my own purposes.

I raised my gaze to meet the pixie's petrified stare.

"'A taste,'" I repeated, my voice devoid of the hunger from before, replaced by a flat, professional coldness. "Well, I hope it was worth it." A slow, humorless smile touched my lips. "Because I have to imagine the punishments for grand larceny are... quite severe in this city. I wonder what the inside of a Makai prison cell looks like. Shall we find out together?"

The pixie flinched, as though my words had been a caustic salt thrown into an open wound—her tiny wings buzzing with agitation. The fear on her face was swiftly replaced by a seething, impotent rage. Her small hands clenched into fists, and a low hiss escaped her lips, her defiance warring with her terror.

The poltergiests, however, showed no such defiance. Their dusty forms, which had wavered with fear before, now seemed to be on the verge of dissolving entirely. The warrior ghost I had pinned let out a low, mournful keen—a sound of pure dread.

The Violin Banshee, cradling her wounded arm, turned her eyes to the furious pixie.

"It is not worth it," the banshee whispered, her voice like the scratching of a broken string, all its former melody gone. "Forget the fabrics; forget all of it. We must leave this place! Now!"

I found a strange and clinical fascination in the moment, much as a naturalist observes the discord of a breached ant-hill. I was witnessing the exact fulcrum point upon which a creature's defiance breaks and gives way to simple, animal terror. The diminutive pixie trembled, her gaze darting between the glittering hoard she had lost and the phantoms of her craven compatriots.

The phantoms, true to their insubstantial nature, offered no such drama. They simply ceased to be, bleeding through the solid stone of the chamber wall like watercolour spilled on parchment, their sorrowful forms becoming one with the shadows from which they were perhaps never truly separate.

The pixie, finding herself suddenly abandoned, emitted a piteous squeak and turned to flee. But her panic was a clumsy and frenetic affair, whereas my new limbs possessed a silent and inexorable grace. To my newly altered senses, her briefest hesitation stretched into an eternity, the world slowing to a strange and lovely crawl, as if time itself had become a thick, viscous syrup. There was no need for a vulgar dash, no rude exertion of effort; I simply willed myself across the orrery, a silent and languid thought made manifest.

My hand, with a gentleness that belied my intent, closed around her. Her agitated buzzing was a faint, amusing vibration against my palm, the protest of a captured hummingbird. She was a warm, struggling jewel. I opened a deep pouch within my jacket, a space secured by one of the ornate, serpent-wrought silver buttons, and placed her inside, fastening it securely. I felt the frenzied, helpless fluttering against my ribs, a trapped bird's heartbeat. Her tiny, muffled curses were a rather charming, if impuissant, display of fury.

There was no need for haste. The trail of the spirits was a thread of incorporeal, gelid thread I could now feel in the very air. With my new... specimen... secured, I ascended from that sad, glittering nursery of ghosts. This curious affair, I mused, was becoming rather diverting.

Please sign in to leave a comment.