Chapter 11:

Chapter 10 — Between Markets and Prayer

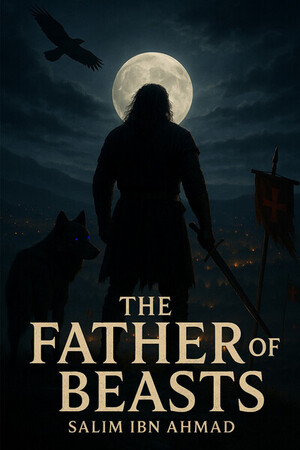

The Father of Beasts

Morning light filtered through bare branches as Ahmad crouched in a pocket of scrub beside a stream. Nahhas pressed his great head into Ahmad’s hands, rumbling with pleasure while the hunter scratched the wolf’s ruff and rubbed behind one scarred ear.

“You kept me standing yesterday,” Ahmad said, voice low. “You always do.”

A soft thump landed on his head. Reeh. The hawk’s claws sank into his hair like she owned it. She bent and tapped his forehead with her beak, starving for attention.

“All right, little queen,” he said, tipping his head so she could nudge the crown of it. He ran two fingers along her head, then behind her neck where she liked it most. Reeh closed her eyes and made a pleased sound.

Adham protested from the stream, as if reminding them he existed. Ahmad stood, crossed to the stallion, and stroked the black neck, palm to muscle.

“You carried me through the ash,” he murmured. “You’ll carry me farther yet if Allah allows.”

For a minute, there was nothing but this small family and the cold water. Then he shouldered the day. He checked the bowstring, tightened the hawk’s jesses, and slung the empty feed-bag across the saddle. Time to trade.

The land south of Arqa ran softer than the high country—richer soil, lower ridges, villages tucked like nests into folds of earth. The main host had passed this way: cut beams, hacked hedges, wells with severed ropes. Ahmad stayed on lesser tracks that skirted orchards and old terraces, entering a hamlet from the open instead of bursting through a lane. Fear grows from surprise. He would not arrive as a raider.

Children saw him first and froze. The wolf at his stirrup, the hawk on his fist, the black horse—stories had outrun him. Women stepped to doorways and went still. Men by a low market ring of stones set down their tools and watched.

“I come to trade,” Ahmad called plainly. “Nothing else.”

That broke the air. A few stalls creaked open—reed mats, patched awnings, thin tables. A smith with burn-scorched beard. A leather worker. Two grain-sellers with little to sell.

Ahmad swung down and set trophies on the stones: two Frankish swords, nicked and dull; a bent helm; a small mail shirt crusted with smoke.

“I need a blade,” he said to the smith, direct as a hammer. “Curved. Damascus work. No gilding. Balance forward enough to bite, light enough to draw twice. Good steel, no show.”

The smith looked from the wolf to the hawk to the man and decided to treat him as a buyer, not a tale. He went to a chest and unwrapped a blade in old cloth—a Damascus saif (sword) with a tight pattern in the steel. No ornaments. Only a line of fuller that promised the cut.

Ahmad lifted it, swung once, reverse and return, then checked the weight with a short wrist cut. He eyed the edge. “This will do.”

“Anything else,” the smith said.

Ahmad tipped the Frankish pieces with a boot. “These, plus arrowheads and a file.”

The smith’s jaw moved, counting in his head. “Add the helm and I’ll include a quiver. Stitched tight. No fray.”

“Done.”

They sealed it by hand, not word. Ahmad slid the new blade home into a plain scabbard. He tried the draw: clean. The re-sheath: smooth. He took a small bundle of bodkin points, a flat file, and a pot of oil for strings.

From the leather worker he chose a new bow-grip and a spare sling pouch. From a fletcher’s basket—a surprise—he picked twenty good shafts, straight-grained, fletched tight. He paid with a Frankish dagger and a length of chain.

The grain-sellers brought a single sack forward and apologised with their eyes. Ahmad shook his head. “Keep it. You’ll need it more than I will.”

Whispers knitted around him, not fearful now, only intent. A boy edged closer than his mother liked, wide-eyed at Nahhas. “Does he bite?” the boy blurted.

“If he must,” Ahmad said. “Not if you’re wise.”

The boy’s hand hovered. Ahmad nodded once. The boy touched thick fur and sucked in a breath at the warmth beneath it. Reeh, jealous of attention, hopped from Ahmad’s fist to his head again. This time a few men laughed, surprised at the sight of a hawk sitting like a spoiled cat on the “Father of Beasts.”

“Show-off,” Ahmad told her, with a smile. Reeh clicked as if agreeing.

By the stream he worked fast: oil on bowstring; file on a nick in a hook; check of Adham’s hooves; burrs pulled from Nahhas’ coat. Quiet, practical care. The kind that keeps a man and his beasts alive.

An elder with a staff approached, flanked by two others. “Word comes from the north,” he said. “Arqa is ringed. Tents like fungus after rain. They’ve been there a few days. Some say a week.”

“How many?” Ahmad asked.

“Too many.” The elder glanced at Nahhas and lowered his voice. “Will you go there?”

“Yes.”

“You’ll find little safety and less food.”

“I’m not going for food,” Ahmad said.

The elder searched his face for a long moment and found whatever he needed to find. He inclined his head. “If any pass this way fleeing, we’ll take them in. If any wear white cloth with red marks, we’ll vanish into the hills.”

“Good,” Ahmad said simply.

He carried water to the bank and washed—hands, mouth, nose, face, beard, arms to the elbows, hair, ears, then feet—slow and exact. He spread his cloak on clean ground near a tree. Nahhas lay down and guarded behind him with his chin on his paws; Adham grazed; Reeh circled once and settled on a branch to watch.

After he finished, Ahmad raised his hands. He didn’t speak long. “Allah, have mercy on the weak. Strengthen the hands that will defend the weak. Keep my aim true and my path straight.”

After some time, a woman near the stream made space for him to pass. “They call you many things,” she said. “Whatever you are, may Allah guide your path.”

“If Allah Wills,” he answered.

He strapped the new blade tight, slung the quiver, checked the hawk’s jesses, and swung into the saddle. The stallion felt the change in him and arched his neck. The wolf rose, ready as ever. The hawk took to the air.

Ahmad looked once around the small market—at the boy who had dared touch a wolf, at the smith who had traded good steel, at the women who had not panicked when a man with beasts walked in. Then he turned Adham toward the south road.

“Arqa,” he said to no one and to all of them.

He didn’t think twice. He didn’t ask for help. He set the stallion to an easy trot and let the village fall behind, a thin curl of smoke rising clean in the morning air. Ahead, somewhere beyond the low ridges, a ring of firelight and banners waited around a stubborn city. He would go and stand where he could make the most hurt with the least waste, and if men wanted a story to tell about the “Father of Beasts,” they could tell it after the work was done.

Please sign in to leave a comment.