Chapter 9:

The Law and the Gallows

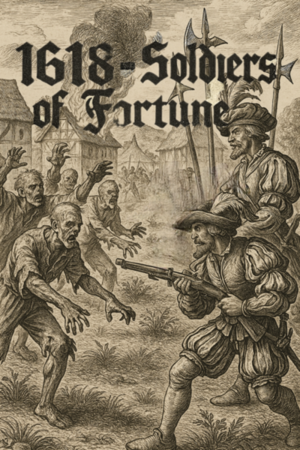

1618 - Soldiers of Fortune

It was already late in the afternoon, and as I made my way through the streets I noted how swiftly horror becomes habit to the mind of man.

The moaning of the walking corpses, the lamentations of those driven out of their senses, the stench of death rising from every square and alley.

These things still seemed unreal for me, like the remnants of a fever-dream.

Yet while I kept to my errand, they receded, held at bay by habit alone.

How long such a defence might endure was another matter.

Since the Hauptmann had not told me where he was to be found, I deemed it prudent to return first to the Obrist’s residence.

The smoke from the pyres had thinned somewhat, though the cries of grief, despair, and rage remained unceasing.

When I gave my name at the door and stated my business, the guards admitted me at once and brought me into a chamber where Hauptmann van Arens awaited.

“There you are,” he said. “I thought you run off. Well? Were you successful?”

It surprised me that, despite his former scepticism, he allowed a glimmer of hope to show.

“I was, Hauptmann. At Woadwork Klenze there are near fifty crossbows to be had, and in good order.”

His eyes widened.

“What did you say? Fifty?”

“Indeed. The bowyer had a considerable stock remaining. And bolts besides.”

At that he struck the table with his fist and stood straighter than I had yet seen him.

“Fifty crossbows. By God, that may yet serve. Woadwork Klenze, you said? I shall send men at once.”

For a heartbeat I thought this might weigh in my favour.

Then the Hauptmann was already calling for messengers, rifling through parchments, and issuing orders with renewed vigour.

Only after several seconds did he seem to recall that I stood still before him.

“I had almost forgotten you. This was well done. If we survive, I shall speak of you to the Obrist. Go to camp now and report to the profos. You will hear the rest there and rejoin me on the morrow.”

That task sounded familiar.

Hauptmann Harrer had meant to send me to the profos, before all had descended into blood and madness.

I made my way toward the camp, though I had no clear notion of where precisely I should go.

Landsknechts lounged before their tents, gambling, sharpening blades, or smoking their pipes.

Some wore ragged grey coats; others strutted about in bright garments with gaudy plumes.

Yet in all of them one saw the same breed: mercenaries to the bone, with their love of colour and excess, their swagger and their squalor.

Sutlers cried their wares, whores called softly to passing men, offering either their bodies or what passed among them for solace.

Often enough such arrangements turned, if not to love, then to something resembling mutual reliance.

The camp was loud, boisterous laughter here, drunken groans there, and arguments everywhere.

Those without tents had pressed themselves beneath the arcades of nearby houses or into narrow alleys, much to the displeasure of those trying to pass.

Although Hauptmann van Arens had not specified where the profos kept court, it soon became apparent.

Only one quarter of the camp possessed the solemn order of authority.

In the broadest part of the square stood a line of dark blue, almost black, tents, guarded by Landsknechts with stern faces.

From here the profos enforced discipline, and the gallows erected nearby bore grim witness to the rigour with which he did so.

A dozen corpses already hung there, swaying in the wind.

Considering that the camp had been forced into the city but one day past, it was a sobering number.

Yet harshness alone kept chaos at bay.

Wooden boards hung from the necks of the hanged, marked with words I could not read, though I could well imagine their meaning.

Most were likely thieves and murderers, but also two very young women hung among them, their bodies marked by wounds that suggested their end had been neither swift nor merciful.

Whether they had earned such an end, I could not say.

One of the guards noticed me staring and nudged me.

“Take a good look. That is what comes of ignoring the rules.”

After I told him my errand, he led me to one of the larger tents and announced me to the profos.

The man sat at a table, head bent over a sheet of parchment.

“Name?” he asked, without looking up.

“I am...”

“Never mind. Just tell me what you want. The day is short and my work is long.”

He was a man of middle years, with a thick moustache and dark, curling hair, dressed in a yellow-and-blue overcoat and green slashed hose, with a broad-brimmed hat of matching hue.

“I come from Hauptmann van Arens,” I said. “He told me to report to you.”

At this he looked up and scrutinised me.

“Didn’t think he’d manage to scrape together so many,” he muttered. “No matter. How long have you served under the Obrist?”

“Since midday,” I replied.

He snorted.

“Another merchant’s son, then. But know that you will find little safety in van Arens’ Fähnlein ¹ , that much is sure. Are you familiar with the field regulations?”

I shook my head.

“Very well. We shall be brief. There is to be no stealing, no looting, no murder, and no rape.”

He recited the words as though from long habit.

“The townsfolk are to remain unmolested unless the Obrist gives contrary orders. You obey promptly; if you do not, you will answer to me and the gallows. The right of assembly and vote is suspended. All decisions lie with the Obrist. If you attempt to flatter any civic official, you will find you waste your breath. The last fools who tried to hold their own council…”

He jerked his head toward the gallows.

“To prevent the ruin of coin, prices have been fixed. Usury is punishable by death. Pay is reduced to two Thaler a month; since prices stand firm in the city, that is more than enough.”

He folded his arms.

“Any armour, weapons, or goods you chance to find are to be brought at once to a superior or the quartermaster. We sell such items cheaply to the sutlers and taverns of the tross, so that trade may continue in some fashion.”

The word trade sounded strained on his tongue.

“Whoever harms that balance harms order, and that, too, is punishable by death. Understood?”

I inclined my head.

“Good. Put your mark here.”

He produced a prepared scroll, tapped the place where I should sign.

I made a simple cross, lacking both the skill and knowledge to do otherwise.

He tossed the parchment behind him onto a growing pile.

“Since you belong to Hauptmann van Arens’ Fähnlein and will take part in a perilous venture, you receive one Thaler in advance. Spend it today, unless you wish to save it for your ferryman on the morrow.”

He handed me the coin with a cynical little flourish.

“You will find your Fähnlein by the dark red tents at the far eastern edge of the camp. And remember, you are responsible for your own equipment.”

His gaze lingered briefly on my crossbow before dismissing me.

“Good luck,” he said.

And with that, my briefing was done.

A guard escorted me back out into the wind and noise of the camp, the coin heavy and cold in my hand.

Glossary

1) A Fähnlein was an infantry unit in early modern German mercenary armies, nominally numbering several hundred men.

Please sign in to leave a comment.