Chapter 8:

The Bowyer

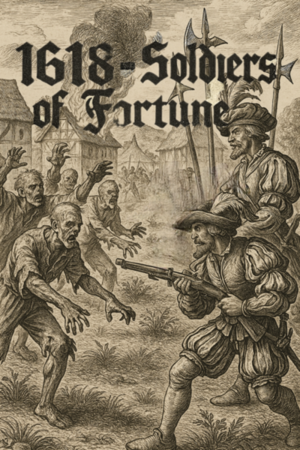

1618 - Soldiers of Fortune

I was in no great haste to undertake the Hauptmann’s errand, though I could not deny that it lay in my own interest to see us furnished with such weapons as it might keep us alive a little longer.

Thus I stepped out of the armoury and considered what might yet be done.

Search the city. Fashion them yourself. Steal them from the watch, van Arens had said.

A most enlightening instruction.

Fashion them myself... did he truly take me for a bowyer? ¹

I scoffed at the notion, but halted mid-stride as a thought struck me.

“A bowyer...” I murmured. “Aye… of course.”

If any man yet possessed crossbows within these walls, it would be such a craftsman.

Crossbows had long fallen from favour in war, yet hunters and city burghers still prized them for smaller game.

It seemed likely that Woadwork Klenze, a small hunting shop near the eastern barricades, had escaped looting, for few of the Landsknechts would know of it.

I had never set foot there myself, but I had heard that the place had once done a brisk trade.

With that hope in mind, I made my way there at once.

But what met my eye from without was not what I had expected.

The door half-rotten, patched with strips of hide, the shutters nailed fast, the windows foul with years of smoke and grime.

Yet through the filth I glimpsed a faint shimmer of light.

Someone was within.

I rapped hard upon the door, waited, rapped again.

No answer came.

Perhaps they did not hear. Or would not answer.

I had no intention of returning empty-handed to the Hauptmann, so I tried the door.

Stiff though it was, it yielded.

A choking reek of strong drink met me at once, mingled with the sour odour of decayed wood.

Tools lay scattered across the floor; bundles of sinew, bowstaves, and half-finished pieces crowded the benches.

For a moment I thought soldiers had already rifled the place.

Yet the storeroom proved well stocked.

Hunting bows of fine workmanship stood in neat rows.

As I lifted one to examine its carving, my eye fell upon a heavy chest in the corner.

I set the bow aside and raised the lid.

At the sight within, I could not keep from laughing aloud.

A good dozen crossbows lay packed in careful order, each in such condition as though it had only lately left the craftsman’s hand.

And when I looked around, I found more hung upon the walls and stacked upon shelves, so that their number together must have neared fifty.

Fortune, for once, had remembered me.

I was searching for a particularly well-made piece to present to van Arens when a loud clatter sounded from the rear, followed by muttered curses.

A door flew open and a figure lurched forth, more swaying than walking.

In one hand he clutched a bottle; with the other he steadied himself upon the frame.

He was an older fellow, his beard matted into a greasy tangle, his eyes bloodshot, his clothing stained and torn.

A pitiful sight, and foul-smelling enough to fell an ox.

“What are you doing here?” I demanded.

He blinked stupidly, drew breath, and attempted to stand straighter.

“If... if anyone…” he slurred, “…hic… ought to be asking questions… it should be me…”

“What?” I snapped.

“You’re the intruder,” he insisted, “and I… I ask the questions…”

“I am here on behalf of Hauptmann van Arens,” I said. “I seek the bowyer. Have you seen him? And how long have you been hiding here?”

At length he seemed to grasp my meaning.

“What do you want with me?” he muttered. “A Landsknecht, then. Take what you came for… and leave me to drink.”

I studied him a moment.

“So you are the bowyer,” I said.

“Who else?” he grumbled, then pitched forward in a heap.

“Wonderful,” I muttered.

I dragged him to the wretched bed in the adjoining chamber, where the stench was abominable, and returned to the storeroom to continue my search.

After some time spent examining the crossbows and counting them, I heard another thud.

The fellow had rolled from the bed and now fumbled blindly for a bottle.

“You have had your fill,” I said, moving the bottles out of reach and hoisting him up again.

“What do you still want?” he groaned. “Take what you came for… and begone.”

“I intend to,” I replied, “but you will first tell me what befell this place.”

He sighed deeply.

“Bring me water. My throat is too dry for long talk.”

I fetched the bucket, and he drank greedily, then splashed water upon his face.

When he brushed back his filthy hair, I saw the weary sharpness in his eyes.

“How old are you, boy?” he asked.

“I never counted.”

He nodded. “Nor I. Too many winters, that is sure. Some good, most ill.”

After a pause he continued, more soberly now:

“It began years ago, when hunters still sought my tools. My work was praised across the Empire; even noblemen paid handsomely. With the Hanse’s help, my bows and traps travelled further than I ever did.”

There was pride in his voice now, faint though it was.

“But I was not content. I wished for more, and so I meddled with the very form of my craft.”

“The form?” I asked. “In what manner?”

He gave a thin smile.

“Have you ever heard of Archimedes of Syracuse?”

I shook my head.

With sudden vigour he rummaged through a dusty shelf and produced a narrow wooden case.

Within lay a contrivance of pulleys, gears, and levers, a confused marvel to my eye.

Seeing my bewilderment, he snapped open parts of the frame: two double-bows unfolded; a grip locked into place; a lever drew back both strings.

A crossbow, though of a kind beyond my imagining.

“This was to make me immortal,” he murmured. “Instead, it ruined me.”

He let the device fall to the floor and sank back upon the bed.

“What happened?” I asked quietly.

“I sold a prototype to a Lord,” he said bitterly. “I had used yew, cheap, easily worked. I misjudged the strain. The bow shattered in his hands.”

He winced. “His hands broke but he lived. My reputation did not. I paid him near all I possessed. The Hanse abandoned me. I was finished.”

He gestured weakly.

“Since then I lived on scraps… until these past days, when the world itself began to rot.”

“So you know of what troubles the city,” I said.

He gave a short nod.

“Of the dead that will not stay dead? Aye. I have heard enough.”

He regarded me keenly.

“Muskets avail little against them, then.”

I inclined my head.

“They strike true only when one hits the skull.”

He barked a laugh. “They called crossbows relics,” he said. “So the wheel turns.”

“So… may I take them?” I asked.

“I said you might,” he replied. “Just because I am drunk does not mean my word is void.”

He lifted the strange mechanism again and pressed it into my hands.

“And take this as well. No yew, but steel. It will drive a bolt harder than any bow. The shorter and stiffer the shaft, the greater the force.”

I stared at him, astonished.

“Go on, take it” he said, his eyes brightening. “Think of me when you put them down.”

After expressing my thanks and securing his unusual gift, I made my way back toward Hauptmann van Arens to deliver the welcome news.

Glossary

1) A Bowyer was a specialised craftsman who made bows, crossbows and other hunting weapons. Bowyers often served civilian markets long after such weapons had declined in military use after the invention of firearms in the 16th century.

Please sign in to leave a comment.