Chapter 8:

Teaching a New Dog Old Tricks: The Trail of Life

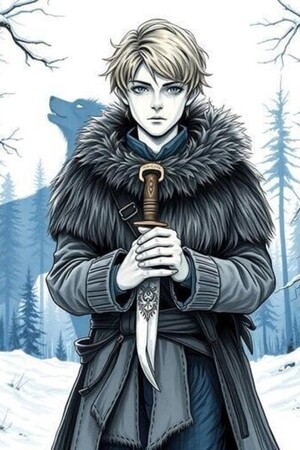

SNOWBOUND

Grooowl!

A sharp pain gnawed at my gut.

Not this again.

I could manage another night without food—maybe.

Kol definitely couldn’t.

I pushed myself upright, careful with my injured arm.

Crack.

…Okay. Didn’t like that sound. But otherwise—

“I’ll be quick,” I told him.

Outside the ravine, the storm had weakened just enough to give me a few feet of vision. Snow swallowed each step as I moved through the trees, knees sinking deep. I listened for anything—rustling, snuffling, the telltale crack of ice under hooves.

Just me and the forest.

I exhaled. My breath curled upward, pale and fleeting.

There—a faint shuffle to the left.

A Snowshoe hare.

I stalked it clumsily at first, then circled wide. Knife numb in my fingers, I climbed a pine tree – the only hunting skill I could truly claim. When the hare paused near a fallen log, I struck.

Father would’ve been proud.

Kol, too.

I returned to the ravine with the hare and skinned it clumsily, nearly slicing my thumb twice. The meat hissed as it hit the flames. Fat sizzled. The smell filled the cave, rich and grounding.

Kol stirred weakly. “Irry…?”

“Yeah,” I murmured, brushing damp hair from his forehead. “It’s me.”

His hand lifted, trying to reach mine, then fell.

“I’m sorry,” I whispered. “For everything. For… all of this. It’s my fault.”

My voice cracked. “I won’t let you die. I swear it.”

The storm lasted one day.

By the end of it, color had returned to Kol’s skin. Not enough to call him healed—but enough that he could walk, leaning on me. We followed the map’s charcoal trail toward the marked circle, resting often. It took one more day.

“Just a little farther,” I whispered. Mostly to myself.

The trail home was not kinder.

Narrower than I remembered. Steeper. Longer.

Kol leaned on me more with every mile, his weight familiar and unbearable all at once. When he stumbled, I caught him. When I faltered, he did the same.

The snow thinned as we descended. Pines gave way to scrub. Then bare rock.

Smoke reached us before sound.

Kol lifted his head. “You smell that?”

“Yeah.”

Home.

The village emerged slowly through the trees—low roofs sagging under snow, fences half-buried. For a moment, I just stood there.

A shout rang out.

Then another.

Someone ran.

“Hunters!” a voice called. “Hunters returning!”

People rushed forward, boots crunching, hands grabbing our arms, our packs, Kol’s weight lifting from my shoulders at last, my knees buckled.

Strong hands caught me before I hit the ground.

“Irrythik.”

Uncle Torran.

His beard was thicker than I remembered, entangled with more white. His eyes, though, sharp as ever.

“Welcome back, nephew,” he said, squinting. “Or should I say… Chief.”

He slapped my shoulders hard enough to nearly drop me again.

“Careful there,” he laughed. “Can’t have you dying before the elders finish arguing about your worthiness.”

“Yeah,” I muttered. “Guess not.”

He studied me suddenly, amusement fading. Without warning, he cupped my face and tilted my head side to side like I was a child that took a bite from the pot.

“You look different,” he said.

“I froze for ten days,” I grunted. “That usually does things to a person.”

“No,” he said, shaking his head. “This is different-different.”

He stepped back, nodding to himself. “Huh. I’m usually not wrong about this stuff.”

I snorted. “You once blamed a missing pot on a jealous mountain spirit.”

“And I was right,” he said. “That pot never turned up.”

Did I mention that Uncle was weird?

He gestured toward the old chief’s fire pit, long unused but never dismantled. We sat there, shoulder to shoulder, as children fed it fresh wood.

“You finished it,” Torran said quietly.

“The ritual?”

He nodded. “Every part that mattered.”

I frowned.

We sat in silence for a moment before he spoke again.

“Irrythik, do you know what a Kodiak is?”

Kodiak was not a name but a title of the tribe’s chosen warrior. Usually hidden, they ensured ita-kkmiq was fulfilled.

And apparently, Kol had been mine.

Chosen by Uncle.

For context, Kol was Uncle’s adopted son which also means he is sort of my cousin.

“Why Kol?” I asked.

“Why not?” he simply said.

That, to him, explained everything.

“I didn’t have a specific reason,” he added. “Odds were he’d get injured.”

“He did,” I said.

“That is true.” He smiled faintly. “But he got you through. And you helped him too, didn’t you?”

I stared into the fire. “So… it counted? I passed?”

“For the most part,” he said. “The ita-kkmiq is more a searching than a ritual.”

He laughed, shaking his head.

“What?” I asked.

“You know I had this same conversation with your Irrykaen.”

My chest tightened hearing father’s name.

Growing up, I always thought father was so great that nothing could hurt him. And it wasn’t just me that thought this. The village too and of course his older brother, hence why I asked him the following question.

“Why didn’t you become chief instead of father?”

He was quiet for a long moment.

“I’ve been asking myself that same question since Irrykaen passed,” he said. “I was the firstborn. Knew the trails and could wrestle a moose with my bare fist.”

He glanced at me. “Perfect, some said. But every time I imagined sitting in that seat… something twisted.”

I knew that feeling well.

“…it wasn’t just hesitation. It was the weight. The expectations the village and my father had for me. And in the end I chose not to bear them but..”

“But what?” I asked, clenching my fist.

“But your father did. He didn’t see it as an expectation; he didn’t feel the weight. Like he used to say, it was simply a choice.”

He placed a firm hand over my knuckles.

“Think about your days out there, nephew. What you accomplished. It was all because of the choice you made. And though I did ask you to do the ritual….my intention was not to make you chief. I know it seems like you’re father was a great man and that was true but he had his faults like all of us. Irrykaen was the right chief for his time and you can be the right chief of yours….if you choose it.”

“What if I’m not ready?” I asked.

“Well, then I’ll have to bear it until you are.” Torran chuckled. “Either way you will still have honored him.”

A boy approached and bowed.

“Chief?...”

We both turned.

“….the elders are calling.”

Torran smiled. “Tell them we’ll be there.”

EPILOGUE

The snow was thinner now.

The world was still covered in white—roofs, paths, memories—but it no longer swallowed the village whole. The sun lingered longer in the sky, its warmth seeping into the ground inch by inch.

Some claimed the Amarok had disappeared and that's why this was happening.

We had begun calling this change the thaw.

And the thaw brought challenges.

“The river ice is thinning early,” one elder said. “The south trail has become uncrossable.”

“We’ll shift the hunt north,” I replied. “There are still boars in that area, but watch out for snow storms. We’ll open the old grains store until then.”

A murmur followed then agreement.

Another elder stepped forward. “The western families request timber.”

“How are we looking on provisions?” I asked turning to my left.

Kol nodded. “Stable—for now. But the eastern families have also made requests. They’ve been short since the forest fire last week.”

“Hmm, then both families shall receive half each.”

A pause followed then someone exhaled through their nose in reluctant acceptance.

“Half won’t last the winter,” an elder said carefully.

“It doesn’t need to,” I replied. ““Only until the thaw. After that, the river will open and hunts will continue.”

Silence again.

This one held.

A child ran past the council ring, nearly tripping over a stack of firewood. No one scolded her. She righted herself and kept running, laughter trailing behind her like smoke.

Kol leaned closer. “The East won’t like this.”

“I know.”

He smirked. “Okay, just checking.”

To my left, Uncle Torran laughed. “I pity whoever has to deliver that message to Aska.”

Both of us looked at Kol.

He lowered his head. “Dammit.”

The elders exchanged looks—some approving, some weary. All listening.

“That is acceptable, young chief,” the eldest said at last. “But we will need permanent answers for the thaw.”

True.

But answers rarely came all at once.

Uncle Torran shifted where he stood, his weight heavy on his staff. He cleared his throat loudly.

“Well,” he said, “if we’re done arguing about snow and grain, I’d like to remind everyone that the boars up north bite back.”

A few chuckles broke the tension.

“Meeting adjourned,” I declared. “Before Torran decides to wrestle the thaw himself.”

The circle loosened. People drifted away—back to work, to warmth, to life. Torran immediately began arguing with a hunter about something trivial, his grin already in place.

I watched them go, my breath curling white in the morning air.

“Careful,” Kol said clapping my shoulder. “If you keep staring like that, someone might think you’re worried.”

I snorted. “I am worried.”

“That’s what worries me.”

He came to stand beside me, leaning on his spear. The scar at his side pulled when he moved—he pretended not to notice it, and I did the same.

“Shouldn’t you get going?” I asked.

“And miss you brooding?” Kol replied. “Never.”

A chuckle is all I gave him.

“Besides,” he added, “I need to finish inventory before heading to Aska.”

Below us, hunters hauled heavy sacks of grain from the storehouse and handed them to waiting elders.

That would do—for now.

“The one I nearly killed myself in to save you?”

“No,” he said. “The one I kept you from dying in.”

We laughed.

It felt longer ago than it was.

Six years since I became chief.

I was still getting used to it.

Kol and Uncle helped—especially Uncle, despite his… ways. More than once, he’d redirected the elders when they pressed too hard.

I caught Kol watching me. He smiled faintly.

“What?” I asked.

“I passed by the ravine yesterday,” he said. “Snow came down so hard I had to wait it out in our spot.”

“And?”

“And nothing. It was just great to see something that was still the same.”

“Yeah. It is nice.”

Some things stay the same.

Others don’t.

I’d learned the difference wasn’t something you fought or chased.

It was something you chose.

Not what to bring back—

but what to carry forward.

And whatever the thaw might bring,

I knew I could live with the trail I’d chosen.

Please sign in to leave a comment.