Chapter 29:

The Decision

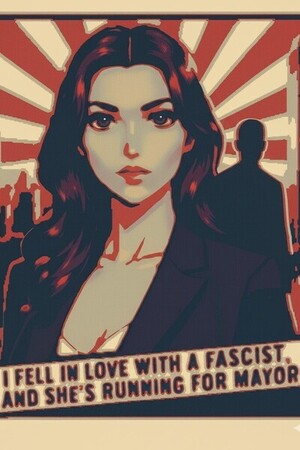

I Fell in Love With a Fascist, and She’s Running for Mayor

A lot of campaign money poured in after the presidential inauguration. She claimed something a couple of the commentators had said during the live coverage of the inauguration when the feed cut away to her was sexist, and got to be the center of a small national news cycle over it. The comments had to do with the bright knee-length red cocktail dress she chose to wear. One talking head said she looked like she got ripped out of a Canadian dystopian novel. The other said she was too old to be wearing knee-length anything, even though he had made his debut on television when color was still a luxury.

Kendra hadn’t talked publicly about running yet, and in the end, Kendra’s decision was anti-climactic. The idea had of course emerged at some point over the course of that presidential election year. I had seen it ebb and flow, and then calcified around the attention the then-former president and now-again president gave her, first within her and then around her.

Kendra’s last campaign for city council had ended in debt, and so for a while she was able to accept contributions. Federal law let her keep taking contributions until the debt was paid off. She had lent her own campaign money, which made this way of collecting contributions tricky.

The renewed media attention in the wake of the inauguration, particularly because she was seen as a younger, female, urban-adjacent version of the now-again president that could appeal to the newer generations, brought renewed scrutiny.

Someone eventually filed a complaint with the election authorities about the campaign contribution situation. They argued that since Kendra could forgive her debts to herself at any point, accepting contributions for that campaign was the functional equivalent of accepting bribes. The election commission didn’t take that argument seriously. Bribery, in the law, is very specifically defined. In general, short of the exchange of specific government services or favors for money or the promise of money, it doesn’t count as bribery.

Nevertheless, the commission was sympathetic to a different argument, that if Kendra was raising this money for a future campaign, those donations shouldn’t be recorded as going to her previous campaign. Normally, that wouldn’t have been such a big deal. With the next election less than two years away, she could launch her re-election campaign committee and start taking funds immediately. Local election rules, however, didn’t let a candidate raise money for multiple campaigns. If she launched a re-election campaign committee, she’d be ineligible to launch a campaign committee for the mayoral race.

Some councilmember had found himself in this predicament a few cycles ago. He had launched a re-election campaign committee while simultaneously launching a mayoral campaign committee. He wasn’t interested in running for both offices. Everybody knew it was a ploy to pressure the incumbent mayor to endorse the councilmember’s re-election campaign, and more specifically to pressure the mayor to funnel donations to his re-election campaign by threatening to siphon donations from their shared donor base during one of the regular internecine fights that flared up within the city’s dominant party.

The councilmember also wanted to double dip on the public funds available to campaign committees. The mayor pressured the electoral commission to step in, and they did, ruling candidates could not establish campaign committees for multiple offices because they could not serve in multiple offices.

The councilmember fought it in court, and actually got that decision overruled. He argued citizens had the right to run for whatever office they wanted, so long as they were eligible. The court agreed, but also ruled that the electoral commission could decline to provide public funds to either of the councilmember’s campaign committees, adopting the electoral commission’s argument that running for both offices opened the possibility of winning both offices, which would make him ineligible for at least one, which by process of elimination made him ineligible for both.

The city charter had a lot of rules passed during the campaign finance reform era that made it difficult to raise money outside of the established campaign committees, and made it difficult to establish campaign committees without accepting public funding. The court ruled that while the councilmember was correct that citizens had a right to run for offices they were eligible for, it also ruled that they didn’t have a right to a campaign committee, which was a legal construct and privilege extended by the local government. Functionally, short of independent wealth, it wasn’t possible to run a viable campaign without a committee. That councilmember ended up dropping out from both races, getting appointed to the board of a long-time government contractor with close contacts with the mayor’s office. It wouldn’t have made a difference, he died before that year’s election.

What that meant for Kendra was that she had to make her decision to run for mayor sooner than later. That was horrible for me. I’d resigned myself to the fact that she was intent on running. After watching the former president get elected again despite the ludicrousness of the proposition, I was no longer so sure Kendra’s mayoral campaign would mostly be an exercise in advocacy and profile-raising at best, and vanity at worst. My last hope was that she would lose the momentum on her own, that the Kendra with doubts would resurface, that she wouldn’t decide to run or not to run, that she’d simply let the lack of a decision make itself. I knew even then that that was delusional. My sense of the possible had grown more realistic since the first time I’d met Kendra.

The decision ended up being a forced one, but not the way I wanted it to be. Because of the campaign committee rules and the universal quarterly contributions report, Kendra needed to make a decision by the end of March, about a year before the mayoral primaries. It was too much money that had come in in the wake of the national attention from the inauguration to leave on the table by delaying the decision. So she didn’t get to do it on her timeline and it ended up being anti-climactic.

She came to me a few days before the March deadline to talk about her decision.

-I do want to run for mayor, she told me simply.

-I know, I said. I’d been tired of fighting and made the peace I could with it. Sometimes she listened to me, and so maybe it wouldn’t be such a bad thing. Even when we fought, our relationship felt strong, the conflicts, mostly managed and choreographed as political debates tend to be, serving to strengthen our tolerance for each other’s flaws, foibles and annoying habits. All politics might be personal but the political, in the abstract, also brings a sense of detachment. And that’s all our debates could ever be, abstract. I held no political power, all I could do was sway her. And in a sense, the way democratic politics work, in the end most of what should do as a legislator also, was sway, either the public or the city government.

-But I’m not going to run if you don’t want me to, she said.

-What? I asked quizzically. Her comment didn’t process at all.

-I want to run for mayor, she repeated. You know that. I know you don’t want me, she added, taking a deep breath. And I’d like you to want me to. And if you don’t, I won’t.

-I do, I said. I seemed more surprised by my answer than she was.

Please sign in to leave a comment.