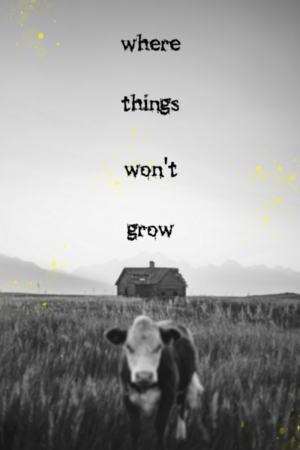

Chapter 1:

Very Last Breath

Very Last Breath

To the untrained eye, the Cartwright farm seemed a nice enough place. Peaceful, if a bit isolated. But looking closer, over Ma Cartwright’s neatly cultivated garden, past old Nana Cartwright in her rocking chair on the porch, one would notice something… unnerving. Not only did the sidings peel, lending the house a general air of long-going decay; not only were the windows covered in rows of thick oak planks; but the Cartwrights themselves carried a mangy, wild countenance, untrained by polite society.Little Grayson Cartwright—barely ten—wondered whether the windows were boarded up to keep danger out, or to keep him in. In his short time on earth, he had never once been allowed to set foot beyond the property line. And so, despite never knowing anything else, he recognized, and more, despised, the backwater bent of his family tree. Not one unrelated soul had come to see the farm in generations, and for decades now, the only occasions on which anyone would leave were Pa’s trips east to sell the fruits of the harvest, or Ma’s infrequent forays into town. And so, since boyhood, Grayson’s lone escape came in the form of the books his mother brought back for him. In books he could see every part of the world he ever wished to. This was, of course, a stopgap at most. Each week he saved his quarters from the firefly fairy, so that one day, when he came of age, he might travel the world. One particular summer evening, he thumbed through his copy of Journey to the Center of the Earth. The pages were yellowed and dog-eared, the margins filled with tentative plans for a journey of his very own. A call came from the kitchen, in Nana’s unmistakable drawly croak. “C’mon youngins! Run on and get you some flies afore it gets truly dark!” Dusk already. With a forceful sigh, Grayson hopped up and stashed his book beneath his pillow, then made his way to the front of the house. Nana stood smiling in the open doorway, waving Grayson and his two older brothers out into the yard. “Hop to it!” she added.“Aww, Nana,” said Grayson. “My guts are all twisted… I’m really not feelin’ well. Could I skip out just this once?”Nana pursed her wrinkled lips and delivered a firm slap to Grayson’s neck. “You better stop tryin’ to lie to me, boy,” she said. “I got eyes in the back of my head. Now, git to work. Miss one day, that fairy’ll get real ticked off and never come again.”Grayson nodded and dragged his feet behind his two brothers, Junior and Jackson, perplexed as usual by the senseless nature of Cartwright family rituals. The trio carried nets as if they were loaded guns, walking the yard like poachers, head on a swivel. A firefly floated by. Jackson, the middle child, sprang forward, trapping the bug in his net and quickly crushing it between his fingers. He then jogged over to a small stone in the grass, lifted it slightly, and placed the little dead thing underneath. In about twelve hours time, there would be a quarter in its place, same as it happened every morning. Nana would again insist that this was the work of the firefly fairy, and Grayson would continue to pretend that he didn’t know the truth.The brothers carried on in the waning light, trapping and killing the fireflies as quickly as they glowed. Seeing the carnage, Grayson couldn’t hold his tongue any longer. “This ain’t normal, y’all know.”Junior chuckled. “What ain’t?”“The damn firefly hunts,” said Grayson. “I’ve read my fair share of books what take place down here south of the Mason-Dixon… not one of ‘em mentions anything like this. It’s strange.”“Sure it’s strange,” said Junior. “But don’t fuss. Nana’s poor heart’ll up and give out. Anyway, it’s tradition. It ain’t natural, and you’re forced to do it. Far as I can tell that’s just what traditions are, so git used to it.”“But where’d it come from?”“What’d pa tell you?”“Some bull-s. He said fireflies bring birds, and birds bring snakes and foxes, and foxes bring wolves who eat little kids. But I know that ain’t true, ‘cause I read there ain’t a single wolf in all South Carolina. Now, come on. I’m ten years old, basically a man. Ain’t I old enough to know by now?”Junior and Jackson stopped and turned around, their faces grim. Grayson stopped short and looked up at them, determination in his eyes. Junior sighed. “Alright, Graysie. I’ll tell you. Lemme think…. I’m sure you know this land used to belong to the Indians. You don’t see any around here now, do you? Well, that’s because when the settlers came through these woods, they burned just about everything in their way. Leather, teepees, bodies. And when they were done, they took whatever was left and buried it right under our feet, then carried on out west. A few years later, our ancestors happened upon this land and decided to set up shop.“Here’s where it gets nutty, kid. Our ancestors realized pretty quick that this place wasn’t right, but all their money was sunk into making this their home, so they had nowhere to go. They lived in fear, and suffered here. What they didn’t know, and what our great-grandpa Jim figured out, was that their problems had everything to do with the fireflies. See, every night, the fireflies remind the native spirits that live here about the night the settlers burnt their village. So our family figured, best not to piss ‘em off, and that’s why we try to catch as many fireflies as we can.”Grayson looked up at his Junior, eyes wide. Then he looked at Jackson, who seemed to be holding back a laugh, and began to pout, which made Jackson burst. “Aw, screw you, J. You’re worse than pa. No wonder don’t nobody come by. We’re a bunch of loons.”Junior smirked and shrugged. As he walked away after a pair of fireflies, Jackson leaned in toward Grayson. Again, he put on a stone face. “Scary as that little ghost story mighta been, it ain’t nothing compared to the truth. Truth is, we Cartwrights ain’t like other families. We got… secrets. Things we’re better off with people not knowin’.”And with that Grayson was thoroughly spooked, although he wouldn’t show it. He rolled his eyes and walked away from Jackson in a huff, fulfilled his obligation to Nana, and started inside. “Gettin’ dark,” he said. “I’m gonna head back.”That night, Grayson lay awake, eyes tracing the grain of the planks nailed over his window. Though his body was heavy, his head spun with the implications of the evening’s conversation. Was there really something wrong with this family? Wrong with this place? There wouldn't be any sleep this night, nor any light to read with, so he needed to occupy himself otherwise.He tiptoed through the pitch dark hall, hands searching the walls and the emptiness before him. His fingers grazed a dull metal hook, apparently meant for holding lanterns, but it was a waste. After dusk, the Cartwright house was lightless. Pa always said lanterns were a waste of perfectly good oil, and electric lights—well, they were the devil’s work. These were clumsier lies than the ones Grayson had learned to pick up on in books, but they were repeated so often that they took on a ring of truth.As Grayson wove through the moon-cast shadows near the porch door, the old floorboards gave a bit beneath his bare feet. Out front, Nana snored softly in her rocking chair. This struck Grayson as odd, because Nana had the nicest bed in the house, and her chair seemed uncomfortable—almost skeletal. Perhaps she had just finished fairy duty, and decided to sit down for a rest.More unnerving was the scene in the yard. Hours had passed since sunset, but Ma, Pa, and Junior were all spread out in the grass, nets in hand. Were they really still at it? Did they ever sleep? What weren’t they telling? Grayson’s confusion turned to rage. If they can keep things from me, I can keep things from them. He padded off into the forest, fully intending to run away and never come back. He didn’t have his books, or even his quarters, but with each springy step he felt more sure he could make do. Half his young life had been spent preparing to get away.But when Grayson reached the property line, something gave him pause. He slowed to a walk and felt it: a feeling like a million eyes watching from the darkness in the trees above. The earth beneath his feet crunched and shifted. He knelt down to get a closer look and realized what the dim moonlight had failed to show him. The substance underfoot was not black topsoil, but thousands upon thousands of dead and decaying fireflies.And from the pile of discarded carcasses emerged a single faint light.*Returning to the house, Grayson was relieved to find that the yard was empty. Still, he kept quiet as he walked up to the porch and—.A calloused hand enveloped Grayson’s upper arm, squeezing and twisting until it stung.“YOW!” Grayson shouted.“Ungrateful little boy,” seethed Pa, dragging Grayson up the porch steps. “What’d I tell you about going out after dark? Next time, I promise you, you’ll think twice about disobeying me under my roof. Crack o’ dawn, you’re going to work.”Pa pulled open the door and, as easily as he baled hay, tossed Grayson into the house. The boy scrambled to his feet and jogged to his bedroom, chin tucked to hide his tears, even in the dark. And when his door was shut, he opened his hand. The young firefly, sitting in his palm, flickered to life. An idea struck.Grayson quickly emptied his quarter jar onto his dresser, then placed the firefly inside. Screwing on the lid, he watched as the firefly’s light grew brighter, and brighter still until it stained the glass. Now, he had a lantern of his own. More importantly, he had a light by which to read after dark. Buzzing with excitement, he pulled Journey to the Center of the Earth from under his pillow, and all through the night, he drifted away to a bigger, better world.*Retribution was swift and merciless.From the time the cock crowed to the evening’s firefly hunt, Pa Cartwright worked Grayson like a mule. Weed-pulling in the morning made knots in the boy’s back. Dead tree removal in the sunny midday brought scrapes and bug bites and sunburns. All day Pa watched like a hawk, quick to interrupt a moment of rest or contemplation. Even when all the conceivable yard work was done, and Grayson tasted freedom, there was more to do. For dinner, he made stew over an open flame, and was not allowed so much as a bite.When dark fell, Grayson was exhausted. All he wanted in the world was to withdraw from the family, climb in bed, and lose himself in a book. But it wasn’t to be.The first thing he noticed, as he stumbled down the hall, was a gentle thrumming noise emanating from behind his bedroom door. Not a cause for alarm in any other house, but on the Cartwright farm, totally out of place. There existed no electrical circuitry, no air conditioning, nothing that would immediately explain such a sound. The second thing he noticed, more alarming than the first, was a repetitive cracking, like someone spilling a bag full of marbles, quickly scooping it up, and doing so again.When he finally built up the courage to open the door, his heart dropped. The room was filled, from floor to ceiling, with hundreds of glowing fireflies. They swarmed like locusts, crashing headlong into the walls. The walls would not budge of course, but the planks covering the window splintered as easily as a dead tree beneath an axe. They crashed, and retreated, and crashed, and retreated again, until moonlight began to spill into the room. A glint of light caught in the broken jar on the floor, and Grayson was left to wonder how one ordinary firefly became so, so many. He stood slack jawed and helpless in the doorway.The planks crumbled to bits and fell away. In one breath, a web of cracks shot across the surface of the dirty glass. In the next, the window shattered altogether, letting the vibrant cloud of fireflies out into the night.Grayson stumbled forward thoughtlessly. AH! He stepped on a piece of the broken jar, slicing the pad of his foot from ball to heel. There wasn’t any time to sulk. Outside, there sounded a hollow, whooping shout, like a wolf’s howl, or a native war cry. Through the empty window, he saw it: From the forest emerged a wall of mist, violently churning and spitting and crackling as it rolled forth. It bore down on the house slowly, but inevitably, passing through Ma’s garden, where the flora wilted and knelt. And the poor fireflies, just escaped, flew straight into the death that awaited them in the mist. In one angry, hissing instant, their light was extinguished.Someone yelped, “Aw, hell!”Leaning out of his window, Grayson could barely catch a glimpse of his brother, Junior, who was leaping off the porch with a little pistol in his hand. Mumbling something quietly to himself, Junior made what looked like the sign of the cross, raised the pistol up at an angle, and pulled the trigger. Instead of a bullet, hot orange light shot from the end of the barrel, tracing an arc away from the house. Before it could get very far, specterly tendrils rose from the mist and, in a whip-like motion, intercepted and smothered the flare. Junior quit his prayer and cursed, frantically trying to load another shot, doing anything he could to avert disaster, but it was too late. More tendrils slithered out from the body of the mist and, like a gag, they wrapped themselves around Junior’s face. Junior writhed, and fought, and stamped his feet, but with each passing second, the air was drained from his lungs. He fell limp on the porch steps, and the mist—or whatever it was—continued to advance.Grayson needed to find a way out. He climbed through his window and up two stories to the roof, where he stood just above the height of the mist. From there, he saw the terrible truth: the mist touched every inch of the property line and came from the forest in every direction, slowly encroaching upon the house, as if trying to choke the life out of the trespassing Cartwright farm for good.There was no escape, Grayson knew. As screams from inside the house pierced the still night air, he glanced down at his bloody footprints on the roof’s crooked shingles and balled his trembling hands into fists. He thought about saying a prayer like Junior, but he knew deep down that prayer was just another senseless family tradition. Just another lie. Instead, as the mist began to claw for purchase on the worn façade of the Cartwright house, and all was evidently lost, he thought of Jules Verne, whose worlds had given him hope in the darkest of times. He closed his eyes and soothed himself with a passage until he believed every piece of it.“While there is life there is hope. I beg to assert...that as long as a man's heart beats, as long as a man's flesh quivers, I do not allow that a being gifted with thought and will can allow himself to despair.”But this was real life, and belief alone was not freedom, even for a boy with boundless imagination. Indeed, little Grayson was just beginning to believe in Verne's words when he took his Very Last Breath.

Please sign in to leave a comment.