Chapter 17:

[The Pale Glutton] by potadd and dispiritor – The Dazzling Lads

Honey-chan's Winter Resort

By the wayside, underneath a pockmarked frieze and a planter of dripping gold, there is a couple dressed in silks as sheer as cobwebs, their faces painted pencil-thin. I overhear one of them whisper, “You must always look to love, dear.” The other lover does not answer at first, instead choosing to drink deeply from her glass. Then, she begins to recite a poem with a voice that is as thick as honey.

“Once in the skies there lived moons of three,

The smallest and youngest ate two for tea.

He ballooned in size,

Grew ever so wise,

If only we were as ambitious as he!”

The rhyme is childish, and for a moment I am convinced that they intended for me to overhear them, that indeed my inexperience in high society glares through like a corsage on my waistcoat—no, it must be my faded cufflinks, or perhaps it is the way my dress pants are still creased sharply down the middle. But then the two women clash their glasses together, and I realise they are simply inebriated.

My chest loosens. When the women laugh behind their feathered fans, I am almost tempted to laugh with them; they remind me of home, of my own two mothers. But one of them turns my way, and instead I am forced to leave the comfort of the familiar.

I turn to face the grandeur of the Saban. Of course, the main draw are the marvels; even the venue—the Ivory Halls—is decked with magic the nobility consider mundane. Magicians will prepare for their entire lives to display their works at this venue; only those of high nobility could dream of attending, with an exception here and there. Before, I had only heard of the Saban through preowned brochures and secondhand recounts, and there had not been a sliver of hope of our family attending even one such event—but I stand here now amongst noblemen and geniuses, between ivory pillars and ivory halls. I press my fingers against the edges of a silver ticket in my pocket. It had not been easy, obtaining this ticket.

I stop to marvel at a orrery that is as large as a barn—the planets are orbs of smoothed crystal and spin slowly on their axiis, and the central star is a ball of light that looks as though I could push my hand through—and the dowager from last night stops by my side, her glass heels clicking into the marble. A faceted jade necklace (too big, too polished) bobs at her throat when she smiles at me. I do not hurry away fast enough. I do not pity her dead husband.

I end up sampling the fruit from a magician's magnum opus: an ever-fruiting twig. Each berry is hard, tart, but the nobility appear to enjoy the taste so I pretend along. Another magician offers me a pot with beetles moulded into the ceramic—handmade, he says. When he pours from it, the liquid inside is blood red. It is a hit with the other patrons but I slip away before the magician can convince me to drink. I catch a man in a whip-tight suit marvelling, “This wine is reminiscent of the dust that accumulates on corpses.” Someone clicks their tongue in my general direction.

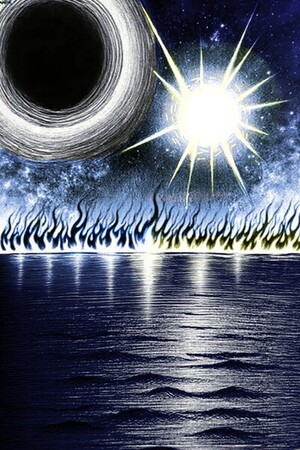

The stars wink down upon me, their presence brighter than ever without the lurid white moon. I should be dancing, or swaying around the ballroom with a glass dangling between my fingers, or enjoying the novelty of a teapot that pours blood instead of tea. Instead I am sober and lost and tired, and I am trying to hide from a dowager who wishes to rekindle an illicit relationship.

When I circle around and meander down the imperial stairs for the third time, glass in hand, there is a man with hair whiter than the snows of Mt. Werner. His suit is surprisingly plain, a sheet of pressed, light paper. To his left are a pair of twins, and to his right is an easel and a glass bottle filled with ink.

He waves and gestures at the easel, the paint, and the twins clap daintily, but my eyes remain on the man in white. There is something otherworldly about the way that he carries himself, like he could float away at any moment. He is like the sun, and I am a sunflower. I cannot stop looking.

And the easel…

I cannot tell what colour is on the easel.

At first I mistake it for a weak yellow, but then it shifts to a cool burgundy, and then I am overcome with the need to watch the skies. For what, I do not know. When the need subsides I look back and the man in white is gone. All that is left is one half of the twins—he is wringing a handkerchief in his hands that is the colour of a dead sky. The colour of a painted easel.

I weave around the halls once more, submerging myself in the bustle of dancers and music boxes. There he is; a shock of white hair! The man in white is delivering a hearty speech to a small, yet growing crowd. I receive a name to go with the strange new colour on the easel, and it is cold, sharp: 'glint.' Again the man passes out glinted handkerchiefs and ties; again I cannot muster the courage to drum up a conversation with him. He spins, and suddenly he is plucking at a stray strand from a woman's beehive with one hand and twirling a skewer in the other.

He flows like hot oil. As if he is liquid gold.

I keep to the backsides of the pillars and trace him to the second floor. Above us are chandeliers piled heavily with scented, burning wax—below us, the bodies of a thousand nobles sway, and I notice that some of them have chosen to pin their handkerchiefs to their corsages, or have chosen to weave them into their hair. Far away, on the other side of the hall, the man in white continues to flaunt.

"Taking a break, are you?"

My face almost crumples; the dowager stands beside me. When I do not respond, she continues, "That man seems to be a bit of an enigma. The older families don't know what to make of him."

"What academy does he hail from?" I ask, suddenly interested.

"He's evaded our questions so far. We suspect that he may be a magician of the…" The older woman produces something from her gloves—a sliver of mundane magic, no doubt purchased from a previous Saban. "...Proscribed variety."

"Then, do we know of his origins?"

"No, but that is neither here nor there. A man presents to you a new colour, and you ask him for the name of his street? He is a living scandal, darling. Do you understand?"

“I do,” I say.

“Never look to treasures you cannot afford.” The widow flicks a fan open; the fan is the colour of pure glint. “Never, never.” Her heels clack against marbled tiles, and to my surprise she is gone.

But within the next hour I am tailing the man in white again through a sea of rowdy investors as they flutter handfuls of notes in the air. Sometimes the man in white smiles and offers one of them a glib response; other times he is gentle, calm. Sometimes money swaps between gloved hands.

Someone wanders through the crowd, striking at a glass with a spoon. I look to the mantlepiece that adorns the furthest wall from me, and see that the shorter arm is almost upright—almost midnight. Immediately the people around the man in white disperse and drift outside, where an open-roofed pavilion rests underneath the stars. Though I wish to make my way towards the man, the crowd has formed a terrible current—by the time I have found my bearings I am already outside, and the man in white is nowhere to be seen.

I cannot allow this to happen. I must find the man, and I feel as though it is imperative that I do so before midnight rears its ugly head and the Saban draws to a close. When I search my surroundings I notice that a large majority of the nobility are already decorated with some form of glint-coloured accessory—a silken corsage at their wrist, a tiny pin embedded in their hair—and my heart shatters.

Though my shoes are not made for strenuous activity, I attempt to shove my way through the crowd, only to find that nobody is moving, and that everyone has their heads craned so high that I see no faces, only long expanses of skin and neck. The fireworks finale, I assume. They are all watching the skies.

But the pavilion is drenched in a strange light, both yellow and burgundy in colour. The woman in front of me seems to dim; her skin loses its natural luster. I look at the skies and see glint.

The sight of it is almost crippling. As I move through the crowd, I see a blot of navy weaving through the glint sky, and I realise that the accessories of the nobles are reflecting into the stratosphere, and that the unsightly blot of navy is my doing. Fatigue bubbles through my limbs. I have always stood out; I will never be one of them.

Never.

Never.

Cold water sluices down my throat. I am inside now, choking down fluids at a fountain that does not seem to be connected to the wall nor the ground. My hands brace against frigid marble as I fight the urge to faint. My blood beats thickly through my head.

And then there he is. At the corner of my eye.

The man in white.

His hair is pearlescent, his eyes a moving pool of pale tints. There is another with him, a woman—my heart sinks at the sight of her. But there is also something very wrong with her, as though she is not aware of the presence of the man before her, as though the sky has her arrested in its sickly, luminous thrall. She too is bathed in that strange shade.

The night is bright, so bright.

The man in white seems to weave around her, as a lover would. I cannot bear to watch, but my eyes betray me; they suffer me so and I cannot look away. His mouth is open, his teeth as white as heated metal, his pale nose against her dark neck. He sinks his teeth into her flesh, and does not move for a long, long time.

My mind flares—a vampire, a demon of the night—but then he rips his head away from the woman, and her neck spills open like a purse, and I realise that the moon is still absent from the sky, and I realise, and I realise.

Bite by bite he devours her lifeless body, and not once does she struggle or splutter, though her lips still move with silent resolve—it is then that I recognise her as the woman from under the friezes. Sometimes she shudders fitfully as if there is a demon within her bones, but still the man eats, and it is almost as if there is an inexplicable emptiness where his stomach should be. When he is done, the crowd in the pavilion still looks to the skies, and I am still crouched at the fountain, and his hands are still dyed rose red because this is all real, a reality that has burned into my eyes by a fire that has crawled free from the confines of its hearth.

Somehow, words still leak from the woman’s body, as though she is a porous sponge.

“Once in the skies there lived moons of three,

The smallest and youngest ate two for tea.

He snaffled their eyes,

Gorged on their thighs,

He'd eat his own skin, if it didn't make him bleed.”

And then the man in white turns to me.

His gaze reeks of hunger.

Please sign in to leave a comment.