Chapter 5:

The Culling

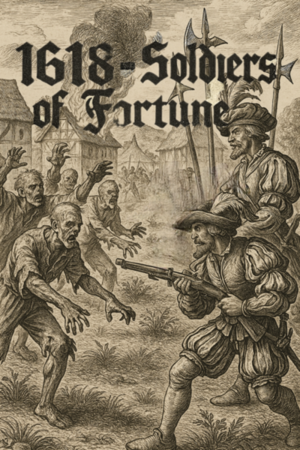

1618 - Soldiers of Fortune

We approached the fish market.

Thick smoke rose in curling columns, and the stench that hung upon the air was grievous indeed, and most assuredly not that of fish.

Von Rundstedt already held a handkerchief before his nose and mouth.

From the roof of our estate it had seemed as though the city itself were aflame, yet now I perceived the truth.

The square was filled with heaps of corpses, piled high one upon another.

Most had already been burned down to blackened bones that yet smouldered faintly while others were only now being laid upon the pyres.

Soldiers hauled bodies by the cartload from houses and streets, casting them upon the mounds without ceremony.

From the far end of the square there came the sharp crack of gunfire.

There an enclosure had been raised, a rude pen hastily fashioned of planks and stakes.

So this, I thought, is where they keep the wounded.

The folk within were of every age and station: citizens and soldiers, clergy and peasants, children and the aged.

Some were sorely hurt, others bore wounds that, at a glance, seemed slight enough.

At intervals a number of them were chosen, led forth, and executed; their bodies were then dragged to the heaps and added to the dead.

I stared, stricken.

“What is this?” I asked. “What is being done here?”

Hauptmann von Rundstedt spoke low.

“It was a hard resolve,” he said. “The Obrist did not come to it lightly. Yet he did what was right.”

He looked at me.

“Most of these people are no longer truly human,” he went on. “Some already carry within them the seed of death. Be glad that you are unhurt, lad; else you would stand in there as well, awaiting the same inglorious end, if you'd show the signs.”

“The signs?"

He saw that I still did not wholly comprehend.

“Come,” he said. “I shall show you.”

As we drew nearer to the pen, I recognised one of Stratweiler’s councilmen being dragged toward it by two soldiers.

Blood ran down his right arm as he struggled and cried aloud.

“It is but a scratch!” he shouted. “I was not bitten, let me go! I am a respected member of the city council, you cannot do this to me!”

The Landsknechts paid little heed to his words.

“The rules are the same for all,” said one of the soldiers.

He had a pockmarked face and could not have seen more than seventeen years.

His companion resembled him so closely, though shorter and rounder, that I took them for brothers.

“You have no say in this,” the younger added. “The Obrist governs the city now.”

The pockmarked youth clearly took delight in tormenting a man so far above him in rank.

“Loose me at once!” the councilman cried. “You shall hang for this, every one of you!”

“Jacob,” the pockmarked one called, “may we not shoot him now? His whining frays my nerves.”

Jacob grinned.

“A fine thought. The bastard will die soon enough in any case, why wait?”

They were already bringing their muskets to bear when von Rundstedt stepped forth.

“Lower those weapons, you good-for-nothings!” he snapped.

The two flinched, plainly having failed to mark our approach.

“Oh, thank you, thank you, Hauptmann,” the councilman cried. “Arrest these scoundrels at once...”

“Silence,” von Rundstedt barked, not so much as glancing at him.

“The man has been bitten, Hauptmann,” the pockmarked youth protested. “He must be put to death at once.”

Von Rundstedt shook his head.

“And what proof offer you?” he asked. “That small wound? The Obrist’s orders were clear: no man is to be executed before he has shown the signs of degeneration. Put him back in the observation pen at once.”

“As you command, Hauptmann…” the two muttered, sorely disappointed.

As they dragged the protesting councillor away, von Rundstedt turned again to me.

“Come,” he said. “Let us walk.”

We moved along the rows of pens.

“The dead make us into their likeness, you see,” he said quietly. “A bite, a scratch, the smallest wound is enough. And the greater the injury, the swifter the fall.”

Slowly, I began to understand.

“It works within a man like a sickness,” he continued. “First he turns cold. Then follow fever and shaking chills. And when at last he draws his final breath, he rises once more, hungry for the flesh of the living.”

He halted and faced me.

“If they lay hand on you, you are lost,” he said. “That is why we show such care.”

Now I understood.

Under such conditions there lay, I was forced to admit, a harsh logic in their methods.

Those judged sound after brief observation were set free, and those already doomed were spared the horror of becoming mindless beasts.

I let my gaze wander, striving to take in the full measure of what passed before me.

Not far off, a soldier was prising a small girl from her mother’s arms.

The child could scarce have seen more than eight years.

She wore a plain linen dress; her skin, where it showed, was pale and crossed with thick blue veins, just as Anna right before she died.

Her red-brown hair clung damply to her face, yet even so her eyes were dull and lifeless.

And yet she still called, clearly enough, for her mother.

Only when the soldier drew his knife and slit the girl’s throat did her whimpering cease.

While the mother sobbed, he cast the child’s body upon one of the freshly raised piles of dead.

I swallowed and averted my gaze.

“How safe are we here, Hauptmann?” I asked, after a moment’s struggle.

Von Rundstedt frowned.

“In this city,” he said, “safe is a word without meaning. So long as these creatures do but shuffle aimlessly and do not lay upon us a true and ordered siege, we are, in some measure, protected. For the present. Until we starve, at least. A month or two, if fortune favour us.”

He paused.

“If but a single bitten man slip past us and infect the rest, we shall doubtless perish far sooner.”

I nodded slowly.

“If I remember aright, there is a bathhouse in this quarter,” I said. “I would fain wash and see to myself ere I am brought before the Obrist, if you allow so.”

The Hauptmann regarded me with some scepticism.

“Are you certain?” he asked. “Those baths swarm with miasmas ¹. ’Tis like enough this sickness began in such places.”

“It is well,” I replied. “If I fall ill, I shall go to the pen of my own free will.”

That answer seemed to unsettle him.

Like many men now, he held that too much bathing weakened the body and bred contagion.

I, however, was raised in the old ways, for my father set great store by cleanliness, and I was seldom ill in those days.

“As you please, then,” he said at last. “The bath-keeper of the East Market is no longer among the living. Or rather, parts of him are doubtless still here.”

He indicated one of the charred heaps with a slight motion of his head.

“You must tend to yourself.”

Von Rundstedt beckoned two Landsknechts.

“Escort this man to the bathhouse,” he ordered. “Then bring him to the Obrist, and see that he does not vanish upon the way.”

The guards nodded and motioned for me to follow.

“And do not keep the Obrist waiting overlong,” von Rundstedt added.

Before I could frame a reply, he had turned and strode away.

The bathhouse was a small green, half-timbered dwelling that stood out clearly from the houses about it.

Beyond the narrow chamber that served as a reception, there was but a single room, low-ceilinged and lined with dark tiles.

At the back stood a great furnace, upon which rested a cauldron of water.

I fed the fire, then poured a few kettles of hot water into the large wooden tub beside the sweat-benches.

When at last I sank into it, the heat spread through my limbs, easing muscles I had not known were clenched.

For a short while I contrived to forget my cares and felt life return to my weary body.

I had no wish to keep the guards, and least of all the Obrist, waiting overly long, so I strove to remain alert.

Even so, I near fell asleep in the tub.

Upon a small table near the benches lay the tools of the bath attendant’s trade: razors for shaving and bloodletting, cupping-glasses, needles, a small mercury mirror, and even a pair of pliers for the pulling of teeth.

Unlike the great bathhouse in the lower town, which was more brothel than house of healing, this little East Market bath still clung to the old practices that had been used here for decades. ²

I attempted to shave myself, yet without the bath-master’s hand it went ill.

After cutting myself a second time I abandoned the effort.

I bathed for perhaps half an hour, then dressed again and stepped outside.

The guards waited by the entrance, speaking in low tones.

The taller of the two was smoking a clay pipe. ³

When he saw me, he bared his teeth in a wide grin.

“Well, lad,” he said, “have you had miasmas enough for one day?”

Both burst into loud laughter.

“Let us just go to the Obrist,” I replied coolly.

“Only jesting,” he said. “Here, take a pull.”

He held the pipe out to me and I took a deep draw while the Landsknecht watched with approval.

“Good tobacco, is it not?” he said. “My brother-in-law is a merchant with the Hanse ⁴. He sent me a small barrel of the stuff some time ago. Straight from the New World.”

I nodded.

“Then savour it whilst you may,” I said. “’Tis likely the last barrel he shall ever send you.”

The Landsknecht frowned.

“What makes you say that?”

“Have you looked about you?” I asked quietly. “Why should it be otherwise elsewhere than it is here? Those creatures have doubtless already reached other cities as well.”

The soldier bristled.

“You cannot know that! And though it were so, have you ever seen Hamburg? ’Tis the greatest cursed city in the Empire. Those things would need to gnaw their way through two-and-twenty bastions and a wall a mile long ere they came near the gates.”

“That may be,” I admitted. “But what avail great walls and stout gates if these creatures rise up within? Hamburg might be as ruined as Stratweiler, all for one infected man who hid his wound.”

The Landsknecht shook his head, as though he would not suffer the thought to take root.

“Let us go to the Obrist,” he said at last, snatching the pipe back from me.

I prayed that I was mistaken.

Yet if von Rundstedt had judged rightly, this plague might spread as swiftly as the Black Death, and that, too, had never been stayed by city walls.

Glossary

1) The Miasma Theory was an early modern medical concept according to which disease was caused by noxious, corrupted air arising from decay or stagnant water and inhaled by the body.

2) Bathing Houses were an important institution of medieval and early modern urban society; contrary to modern assumptions, bathing was common and bathhouses served not only hygienic purposes but also provided minor medical treatments, barbering, and, in some cases, prostitution.

3) Tobacco reached Europe in the mid-16th century and spread rapidly among soldiers, sailors, and other mobile groups, despite repeated attempts by ecclesiastical authorities to prohibit its use.

4) Die Hanse (Eng.: The Hanseatic League) was a commercial and political network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe, active from the 12th to the late 17th century.

Please sign in to leave a comment.