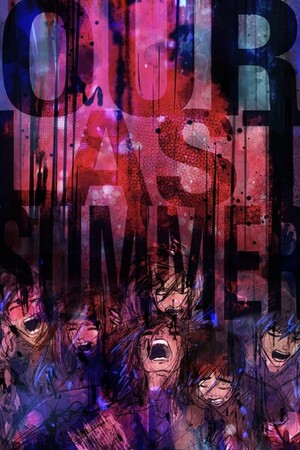

Chapter 5:

He lived for them, bled for them.

Amoria

Some time ago, a storm tore through the mountain. The people ran into their homes and barricaded their doors. They huddled around the oven-fire, though it was never warm enough. Even the great hearth in his father’s chambers had danced weakly.

The mountain folk had a name for this sort of storm. The sort that promised endless snow. The sort that took the old and the young and the sickly. They called it “true winter.”

The boy king felt like he was going through a thousand true winters. He knew not what time it was or how close they were to the peony; only that he was freezing. Walking kept him alive and Amoria’s talks kept him distracted. For that, he was thankful, though he still prayed for warmth.

“We are close,” said Amoria.

He did not reply, for the journey had left him breathless.

Every time he would hunch over and feel as if he was about to hurl, Amoria would stop and wait for him. It was a tedious cycle, one that only looped faster each time. Still, she would never be more than a few steps ahead of him. If he stopped, she stopped. If they were to find the peony, they would do so together.

“Why did you not send your knights?” Amoria asked. She spoke it with every respect, yet the boy could not help but feel it goading. “You did not need to come yourself.”

After a moment of deep breathing, he replied, “A knight’s duty is to the mountain’s walls. A king’s duty is to its heart. No man may carry this burden for me.”

“Spoken like a true king.”

“I am no true king.” He gathered his strength and continued forwards. She continued with him. “I am a child wearing an oversized crown, playing pretend. Please do not sully the title of my forefathers and belittle their hardship by comparing it to a boy climbing a molehill.”

“I am doing no such thing. I have known hundreds of kings in my life, and all but a handful are satisfied sending men to die for their pride.”

“A hundred kings, perhaps, but not mountain kings.” The boy pushed himself to take a few more steps before succumbing to fatigue. The chilled air hurt when he breathed it, and his legs ached even when he was still. “Mountain kings are born from the hardest stones and the brightest gems. They have no birthright to gold or silver; only the dirt on the ground and the strength of their will. They are to ordinary kings what lions are to sheep.”

He dropped to one knee, coughing and gagging. It was becoming hard to see with the heavy snowfall.

Amoria put a hand on his shoulder. “You don’t have to push yourself. You have nothing to prove to me.”

“Do you know what the first mountain king did? He carved a hall below the stones for my people. Pebble by pebble, he chiselled the mountain hollow, until there was space enough for his people to survive. And I can’t even weather the cold.”

“Do not speak to me of the first king’s legend; I was there when it happened.”

For a moment, he forgot the cold. “You never told me.”

“I did not wish for you to compare yourself to him.”

“You must tell me about him. I am of his blood and I have a right to his memory.”

She offered her hand. “I will tell you, but we must hurry. Though I cannot see the sky, I know the day is fading.”

The boy forced strength into his legs and stood. They walked hand in hand, Amoria leading him through the storm.

“When I met your forefather, he was not yet king of the mountain,” she remembered. “He was chieftain of the old Green Lakes. Not of the city, for that had just been overrun by barbarians. He led his people, the townsfolks that will one day become mountainfolk.”

“And the mountain,” the boy pleaded. “You must tell me of how he carved the mountain hollow!”

“Of that, he did not.”

“What do you mean?”

“The chieftain found the mountain, yes. And he was the one to carve it. He hammered away at the stone with his pick, day after day. However, he was frail, and would work at the stone until the very moment of his death. The mountain was vast, and he was only one man, like a bird sharpening its beak upon a diamond alp.”

“So he died before the mountain was hollowed. If so, how is it that my people have made their home there?”

“At the time, he was ridiculed for his dream, for men do not live under mountains. Your forefather did not give up, and died for what he believed would save his people. It was only with his death, that the lake-folk rallied in his memory. It was the men and women and children who each took up a pick and continued where the chieftain ended. Those who had no pick, used shovels, and those with no shovels used their hands. Even a diamond alp would soon be worn away should an entire flock work at it ceaselessly.”

The boy coughed into his fist. Every step he took would smother his leg in snow. “So he died chieftain of old Green Lakes.”

“But he lives as King of the Mountain,” Amoria pointed out. “He forged a lineage that has survived for five hundred years.”

“I…I don’t understand.”

“You think every king before you a monolith, when in truth they were only men. They did not crown the chieftain for his strength; that was a lie crafted by storytellers over generations. No, they crowned him for he dedicated his life to his people. He lived for them, bled for them. And as you have also lived and bled for the mountain, you are every bit the king he was.”

His throat was thick with the beginning of tears. He fought to hold them back, for they would only freeze on his cheeks and leave him colder. Nevertheless, he sobbed. “Thank you.”

❖

“Deathless one!”

The voice was so faint, the boy thought it was his stupor. He realised it wasn’t when Amoria turned, her face shifting into a scowl.

“Get back,” she warned, a hand ready on the pommel of her sword.

The boy obeyed, and watched from behind her cape.

The man was so frozen pale and thin, he seemed almost like a skeleton through the blurry snow. Frostbite had taken him, leaving his limbs black with rot. His eyes looked too big for their sockets and he stared back unblinking. His body was hunched and limp, and it reminded the boy of a marionette, loose from its strings.

It took a second for the boy to recognise him: the first man they saw in the village. The first who begged for food. He could barely stand then. How has be managed to follow them for weeks?

“Deathless one,” the man repeated. Much of his lips had decayed and his teeth were yellow and scattered, leaving his words slurred. “Why have you forsaken us?”

“I have forsaken no one.” She reached an arm over the boy. “There was nothing I could have done, and for that I am sorry. Turn back now. If you shall continue to stalk us with malice, I will strike thee down without hesitation. This is your only warning.”

If he heard her, he did not show it. “Years ago, I worked as a priest in the village. I maintained the only library and there, I spent my time combing through scriptures. Above all, one spoke to me. The scripture said: before there was time…before there was light, before there was anything– there was nothing. And before there was nothing, there was Amoria. I understand what you are now. The reason you did not save us. You are no god. You are the first man, and in that, you are humanity’s first sin. You are the snake that stole us from paradise.”

“I am telling you to leave.”

His palms pulled closer together. The storm was howling now, and his shadow grew to stretch across the white snow. “And I am the righteous. I am the harbinger of the true god, his hand on Earth. Through me, he will bring retribution and justice.”

“I assure you, I have seen divinity, and it is not what possesses you.”

“I sentence you, Amoria the deathless,” he said. His palms connected, completing the pose of prayer. “For the blood of my village is on thy hands.”

Her head shot back. The boy saw her lips move, but the words escaped him.

He blinked. It all happened too fast. The space between the man and them was empty, the snow all vanished in a heartbeat. Amoria stumbled back, struggling to keep her balance. One arm gripped her blade, the other was hidden behind her cape.

No, he realised. Her arm was gone, cleaved off and thrown across the ground, streaking red along its path.

“I said go!” Amoria shouted. He never heard such distress colour her voice. “Run!”

It took him everything to not stay. He had to recognise his own impotence; to realise staying would mean death. He had to remember that he was flesh and blood; Amoria was fire and ichor.

So he ran. As his foot glided off the earth, Amoria lunged at the priest. Her speed was unmatched amongst men, but she had to cross the gap between them in the time his hands returned to prayer. Her sword grazed his neck, before she was sent tumbling back. Somehow, the air obeyed him. It was his hammer, and swung with the force of ten thousand men.

“Witness judgement, infidel,” said the priest. “You are an abomination to creation; exempt to the one true law of nature.”

Amoria crouched in the snow, wiping the taste of iron from her lips. “And you are a man with a capacity for the dark magics.”

“Dark magic?!” His scowl took the entire length of his face. “My newfound ability is proof that I am chosen by god! This is his divine fury given form!”

Amoria found her footing and stood. Her arm had sprouted anew with no evidence of its absence. “If the gods despise their creation so, I will welcome their fury with open arms. I have been awaiting death since its conception.”

“Rejoice then, for I will bring you it.”

She picked up her sword. “You may try.”

❖

Chest heaving, the boy king raced across the white sea. He had forgotten the hunger, forgotten the cold. All he could think about was the peony and Amoria.

She will be okay, he trusted. She is Amoria the deathless.

The intense storm was constricting. He could see neither in front nor behind, and even his legs were swallowed up by the snow. The world had become a bubble, only a hair’s length further from his skin. Yet at the same time, the world had become endless, and he was only a speck in it, the same way a goldfish cannot comprehend the vast sea.

He begged for some sign; some mark that he was even stumbling in the right direction. All he could do was believe he was still facing north, and try not to freeze to death.

When his panic died down, the cold seeped back in. He was moving in fits, begging his limbs to obey. The pathetic distance he had covered with Amoria was a river’s length compared to the inches he was conquering now.

The boy had, at last, thought ‘I am going to die here’, when there was a glimpse of something other than snow in the distance.

Instinct screamed at him and he floundered to the silhouette.

It was tiny, barely the size of his little finger. Its buds were closed tight, with brown blots, as if on the verge of withering. But it was here. It was the peony, his hope, and its pink petals were warmer than any oven-fire.

“Oh gods.” He knew he shouldn’t waste his strength, but he couldn’t stop the words from bursting out of him. “Oh, thank you. Thank you, thank you, thank you. Thank you father, thank you mother. Thank you, oh generous gods.”

“You’re welcome, but I would not be so hasty in celebrating.”

A face loomed over him, skin pale blue. Her loose dress had the texture of glaciers, yet flowed like fabric. Her hair was hoarfrost and her eyes the pattern of snowflakes. When she spoke, her voice was the crackling of rime, carried directly to his ear by the snowfall.

“The hard part starts now,” said the god.

❖

Amoria never dies. Amora was immortal. She could lose her arm, bone and all, and regain it in seconds. Her heart was no more vital than the hair on her head or the nails on her fingers. She could heal any injury, any wound.

Except she was being injured faster than she could heal, and she was beginning to look more like a skeleton than even the priest. No matter how fast she was, it was not enough to outspeed his spell, the casting of which needed only for him to take the position of prayer.

“Your new form is fitting,” remarked the priest. “The body now fits the soul.”

Her throat had regenerated enough for speech, though her legs were still stumps. She needed to buy time. “You did not have these powers when we met. How did you achieve them?”

“I found god.”

“You said you were a priest. Had you not always found god?”

“Like you, I was a heretic then,” he said. “I believed in false idols. The Lord of Famine, the forgotten widow. Amoria the deathless. But they never answered my prayer. You never answered my prayer. So I turned to more obscure scripture.”

The bones of her feet were taking form. “More obscure scripture?”

“The church had banned texts relating to such gods. I see now it is only because they were blind to suffering,” he preached. “I am not. I suffered, and for that, I am blessed. For that, I am– “

Her muscles healed. She vaulted across the plains. Just as his hands were about to touch, Amoria dug her blade deep into the snow like a shovel, and heaved. The air, already heavy with snow, almost shone white, and the priest could not attack what he could not see.

The body now fits the soul, she thought, circling around the priest. You are as blind as your church.

The priest twisted back. He could just make out a shadow through the veil. The pose of prayer connected, and his god answered. The air exploded with such force that, for just a moment, it was free of snow. In that empty space, there were only threads. Pieces of fabric.

The priest had only hit her cape. The realisation hit him too late. He shifted from the decoy, pivoting to his real target.

Her sword flashed. To his credit, the priest twisted away at the last second, barely avoiding death.

Amoria’s momentum kept her skidding across the ground. She flicked her blade as if cracking a whip, and the snow splattered crimson. A moment after, the priest’s arm fell.

“It is only fair since you had taken one of mine,” she said. “Show me your prayer now, you blind fool.”

At first, he grimaced from the pain, one hand clamped on his shoulder, where his limb had sat. Then, he threw his head back and laughed. It was a deep, wild laugh full of giddy abandon. A noise far from human.

“You are old beyond comprehension, yet you are as foolish as a child,” he spoke between fits of mirth. “Arms are merely decorations of the flesh. True prayer is a yearning of the soul!”

He guided his last hand to an incomplete pose. Amoria’s heart ruptured.

❖

“You are a god,” the boy whimpered.

“And you are the mountain king,” said the god.

He would have liked to stand to show his respects, but he had no strength left. “If you do not mind, what are you god of? Where is your domain?”

“I am god of this peony. I am birthed when it sprouts and mature as it buds. When it wilts, I, too, will die. My domain stretches only as far as the cube of soil in which the flower sits.”

“I have seen thousands of flowers. Why does this one have a god?”

She giggled. It was the sound of ice crushed underfoot. “Every flower has a god, I assure you. Only this one has chosen to speak to you.”

“Why?”

“If a flower is plucked, the worst that may happen is an allergy. If this one is plucked, it may save or kill a mountain.”

He took the pose of worship, face braced in the snow. “Tell me how to save my people. Please.”

“Oh, that’s simple.” She shrugged. “You uproot the flower.”

“Really?”

“Of course. Except, the flower has yet to bloom and it is already shrivelling.”

“Is there something I can do?”

“You see, o’ mountain king, the peony blossoms only once a year and only in the coldest winter. However, it is still a flower, and like all flowers it needs warmth. It is a contradictory existence, to need the frigid as well as the tepid.”

“Then I only need to keep the flower warm, and it will blossom?”

The god wore a sly smile and nodded.

The boy ripped off a part of his coat. He dug through his pouch for two lumps of flint, and banged them together by the fabric, hoping it would catch an ember. He kept at it, but the storm was too great. He doubted hell itself could survive this wind, let alone bits of cinder.

Next, he took off every piece of clothing he could spare. Hope dulled his sensation to cold as he wrapped the peony in his coat, and his jacket, and his blanket.

“No,” said the god. “That is not enough. It is still too cold.”

“What can I do? The wind is too great for fire, and my clothes are not enough.”

“I am afraid there’s no advice I can offer you. This is simply the way of the world.”

“No! No, no, no, you must live! You must live so my people may live as well.”

She shook her head. “If the peony cannot survive, it will wither. As roots die without water and beasts die without flesh, nature is as it is.”

Nature is as it is. He was tired of being told that; of being reminded of his youth, his naivety, the futility of every action. He could not save the village, he could not even save the mother and her daughter, and now he was being told he could not save his people.

The boy breathed deeply. “You are wrong.”

The god raised an eyebrow. “Oh?”

His fingers wrapped around his pocket knife. He stared at his reflection in its metal, bit down on a roll of his shirt, and jammed the blade through his palm. Blood soaked the peony and coloured its pink petals vermillion. There was a fizz as hot blood met bitter air.

❖

She knew the same trick would not work twice. The priest knew it too, though it didn’t stop him from blowing away every snow-covered patch from their battlefield.

Amoria gathered herself for another desperate attack. She leapt, sword blurring towards the priest. For a fraction of a second, his arm lingered. As much as he pretended he was fine, Amoria knew the pain of losing a limb and being forced to continue fighting. That moment was all she needed.

Her first target was not his neck, but her own. Blood pooled along her blade and she flung it off. It splashed into the priest’s eyes and froze instantly. He lurched off-balance, desperate to remove the red ice. It did not blind him; only painted his world with a red hue.

His eyes latched to the approaching shadow. It was Amoria’s shape, and he could not mistake it for fabric. He made his prayer. The wind hummed, and the shadow burst into blots of ink.

“You are clever, I shall grant you that compliment,” said the priest. “But in the face of god, your trickery is no more than a child’s pranks.”

Pain blossomed in his chest. His eyes dropped. A white blade had speared his body, and when he twisted his neck back, Amoria stood behind.

His gasp was the last pathetic crackle of a dying fire. “How?”

“Only the simple magics.” She pulled the sword out, and he collapsed. “In the end, you die as blind as you lived.”

As soon as his corpse hit the snow, Amoria ran. She had no time to celebrate her victory; her only thought was the boy, and she found herself praying to the very gods she had renounced. In that sense, perhaps the priest was the one who triumphed.

You have taken enough from me, she thought, hoping one of the pantheon was listening. They always were. You do not claim my life, for you know when I arrive in hell I shall tear it asunder. Take him from me, and you need not wait for my death.

❖

“You will die if you continue.”

“I know.” The boy’s arms were parched, layered with a thousand cuts. They had no more blood to let, for every drop was spent on the flower. “I have always known.”

The peony’s buds were still closed, despite its petals having been drenched red. The brown spots had faded though, and the stem had grown taller. That was evidence enough that his pain bore fruit.

The god’s smile was harsh. “You are only ten.”

“Many will die younger.”

“You have seen nothing of the world.”

He angled the knife at his stomach. “And my people will see it all.”

“Do you really have no hesitation? No dreams? No regrets?”

“I am nothing but regret.” The boy king dug his knife deep. It felt as if his belly was boiling. “But my lineage is one of sacrifice. So many before me have died so that I may live as long as I have, and it is now my turn to give back.”

He dragged the blade across his stomach, splitting it from hip to hip. His life spilt out, smothering the peony with warmth. Darkness gathered at the edges of his vision as the buds unravelled at its centre.

“It’s beautiful,” he whispered, plucking the flower.

The god sighed, content. “What would you like me to tell her?”

“Tell her I was here and I have lived. I created, I laughed, I cried, I loved.” His head dropped back. The snowfall was starting to clear, and he could almost glimpse the clear night sky. In his last moments, he pretended the stars were the crystals of the mountain. “And tell her to please not forget me.”

The boy king’s eyes drifted shut, and he heard his mother calling.

Please sign in to leave a comment.